Usually I don’t allow myself to have favorite artists? Do I prefer Bach to Beethoven? Or to Schubert? But I have to admit that Robert Altman is my favorite movie director.

This doesn’t mean I want to make a case that he is the “best” movie director ever. I don’t believe in such nonsense. I’d never say that Altman is “better” than Kurosawa, Keaton, Bergman, Carné, or many others I could name. But there’s something about Altman’s greatest films that makes me feel especially close to them, and that they do what I want to see more than anyone else’s.

Several years ago my local “art” movie house, Upstate Films in Rhinebeck, had a single showing of “Nashville.” I’ve seen that numerous times, but of course I hadn’t seen it in a theater since it was new. There is one glaring flaw in the film that gets on my nerves: the character of Opal, the British TV reporter played by Geraldine Chaplin. I don’t find her at all convincing, and although I know the stupidity of her reports is intended to make a point I think it’s too exaggerated to be plausible. (I hope.)

Aside from that, though, “Nashville” seems to me a magnificent statement of the state of American culture in the mid-70s (it was made in 1975), as seen through the microcosm of the country music scene in the city of Nashville. I’ve usually found that particular genre of music one of the few I don’t like, and I suspect Altman shared my opinion. As inventive as always, Altman hit upon the brilliant strategy of having the actors who play the roles of singers write their own songs and do their own singing. Some of them can sing, but only Keith Carradine could write a convincing song. (Ironically, it won an Oscar.) So most of the songs performed by these supposed icons of country music are pretty dumb, making in a subtle way a point that could easily have been overstated.

The interweaving of numerous stories in a single film is so much Altman’s invention that anything similar these days is immediately tagged as Altmanesque by film critics. “Nashville” was the first such Altman film to take on such an elaborate structure, although in a less complex construction it’s the basis of his first successful feature, “MASH” (Altman once stated that, although some of his films had lost money for the studios, they still owed him a debt of gratitude for “MASH” because it eventually earned a billion dollars for its studio through sales and TV royalties.) Other Altman classics like “Short Cuts” and “Gosford Park” have similarly complex stories.

“MASH” is only the first of Altman’s great films. Although “Nashville” might be my favorite of all of them, I might also love “3 Women” just as much. That magnificent, mysterious film, not one of his best known, is an exploration of the female psyche so convincing that it’s surprising to learn that Altman himself wrote it. Another of my many favorites, almost unknown today, is “Images,” a suspense story with a stunning shock ending which seems obviously a tribute to Alfred Hitchcock, an early mentor of Altman’s. (Before his successful movie career, Altman worked in television for a decade, directing episodes of “Alfred Hitchcock Presents,” “Combat,” “Bonanza,” and other series. In his mature career he went back to TV for several excellent projects, the greatest of which was “Tanner ‘88,” made for HBO.)

I’m lots fonder of “Popeye” than most critics seem to be. It’s a bizarre musical, with great songs by Harry Nilsson, and Robin Williams and Shelley Duvall are superb as Popeye and Olive Oyl. After that flopped, Altman had trouble getting funding for films for some years, and he worked mostly at making film versions of plays. Among those, “Secret Honor” is truly outstanding, with Philip Baker Hall as an amazing Richard Nixon. (“Beyond Therapy” is the only Altman film I’ve been unable to watch through. I find the Durang script unbearable. Durang didn’t like the film either.)

In the 1990s, Altman’s career had a renaissance. The post-1990 films are uneven, including such artistic flops as “Kansas City” (despite an amazing performance from Harry Belafonte”) and “Ready to Wear.” But they also include such masterpieces as “The Player,” “Short Cuts,” “Gosford Park” and even his last film, “A Prairie Home Companion,” based on the radio program and using some of its regulars (including host Garrison Keillor). When Altman died, he was working on a project called “Hands on a Hard Body,” based on the odd contests held by truck dealers in which the last person standing and still awake with both hands on a truck wins the truck. What a delight that would have been!

I haven’t been spending enough time with Robert Altman recently, but that’s going to change. While clearing out my collection of old VHS tapes I’ve found some Altman material I haven’t seen in years, including an interview done after “Vincent and Theo” was released and several TV projects including two one-act Harold Pinter plays (“The Dumb Waiter” and “The Room”). I’m going to copy all of the tapes to DVD and watch them in the process, and then I’m going start going through the features in a leisurely manner. It’ll probably take me two years or more. But what a trip that’s going to be!

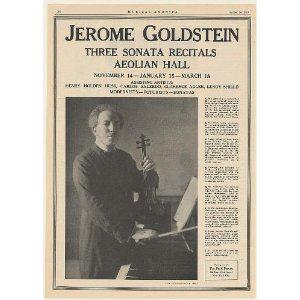

When I was a young man, I became friends with an elderly violinist named Jerome Goldstein, a customer at the bookstore where I worked. I never had the curiosity to discover his distinguished background.

In 1964 I dropped out of Brooklyn College and married a whole family, a woman with three children. In order to support us, I took a job at the Strand Book Store in Manhattan, which was then probably the largest used book store in New York if not the whole U.S. While far from its present total of two and a half million books, it was already large enough to require a full-time book cataloguer, which I became. I worked there for five and a half years before moving to Ulster County in 1970, where I still live.

Any book store buying entire collections is going to wind up with nearly valueless books. The Strand disposed of these on outdoor stands. Several times I encountered an elderly man going through the 10 and 25 cent books with great diligence, and we got to talking. When he found out I was interested in music, he told me he was a professional violinist. His name was Jerome Goldstein.

I usually left work as soon as possible to get home to my wife and family. But Jerome started inviting me to visit him, and eventually I put aside an evening for the visit. He lived in a huge rent-controlled loft, just around the corner from the Strand, on Fourth Avenue. On that first visit I met Jerome’s wife, who seemed to be perpetually angry, and saw the pseudo-splendor in which he lived. The walls were crowded with book shelves and music shelves. A somewhat deteriorated grand piano was almost hidden by piles of tattered books and papers.

When I left that evening, Jerome gave me a pie in a box and told me to take it home to my family. I was suspicious of it, and when I got home I made sure to open it after the kids had gone to bed. It was moldy, probably given to him by a bakery near the end of its expected lifespan.

Jerome told me he had played with the Philadelphia Orchestra when Stokowski was the music director. I figured it was probably true, and it was; the orchestra’s website lists a violinist named Jerome Goldstein who was a member from 1917 until 1921. But he seemed like such a crackpot, although a likeable one, that I found it hard to take him very seriously.

One day he invited me to join one of his evening musicales. I had admitted to him that I played the piano but insisted that I wasn’t very good at it (the truth) and that I had neither the technique nor the experience to play chamber music. But I did mention that I played the first Prelude from Bach’s “The Well-Tempered Clavier,” so he told me to come and play that and that he would play the “Ave Maria” melody that Gounod had fitted to the Bach Prelude.

I don’t remember that we had any rehearsal. When I arrived at Jerome’s apartment that evening, I was surprised to find a rather large audience assembled, at least 50 people. Jerome played some unaccompanied violin music first, and as I expected he didn’t sound at all good. Whatever violin he had played in Philadelphia must have been long gone, and the scratchy sound he drew from his cheap fiddle was hard to take. I suffered through the Bach-Gounod, which I didn’t like anyway.

I continued to see Jerome for another year or two, until he became ill with lung cancer. I visited him in the hospital near the end of his life, and brought away an image which comes back to me whenever I see someone smoking. He was lying in bed, feeble and incoherent, until he thought he saw demons coming at him through the walls. Then he sat up and started screaming at them.

After I left New York, I hardly thought about Jerome until one day when I was looking through a book on Charles Ives and was startled to see a photo of Jerome. The caption indicated that he had been involved in early performances of Ives’s music, sometimes with the composer at the piano. (As his private recordings reveal, Ives was a virtuoso pianist.)

The photo above is from an ad for a series of three morning recitals, with pianist Rex Tilson, given at Aeolian Hall (the place where the “Rhapsody in Blue” was first performed) in 1924. An unsigned review of the last concert, published in the New York Herald Tribune, mentions performances of works by Ives, Milhaud, and Pizzetti, giving “the palm to Pizzetti.” The Ives work was the Fourth Violin Sonata, composed in 1909 and not published until 1951. This was its premiere performance.

The Ives book also mentioned that Jerome had performed with Béla Bartók during the composer’s first tour of the United States in 1926. Doing some quick Internet research I turned up only one other reference to Jerome. He played Henry Cowell’s “Solo for Violin” (with pianist Imre Weisshaus) at a concert of the Pan American Association of Composers at “Carnegie Chamber Hall” (probably the small theater now known as Weill Hall) on April 21, 1930.

I’m sure Jerome was involved in many other interesting events like these. And I wish my callow younger self had had the sense to ask him about his career. I never did.

I just got to see the National Theater of London’s production of “The Curious Incident of the Dog in the Night-Time,” and it set me thinking a great deal about an aspect of contemporary theater. Movies started as mostly filmed versions of what people saw in theaters, but now things seem to be turning around.I am not a frequent consumer of live theater, much as I enjoy it. I do go to see some local productions, which are often good, and I get to New York shows once in a long while. So being able to see high definition broadcasts of these London productions in a local theater is a real treat.

I just got to see the National Theater of London’s production of “The Curious Incident of the Dog in the Night-Time,” and it set me thinking a great deal about an aspect of contemporary theater. Movies started as mostly filmed versions of what people saw in theaters, but now things seem to be turning around.I am not a frequent consumer of live theater, much as I enjoy it. I do go to see some local productions, which are often good, and I get to New York shows once in a long while. So being able to see high definition broadcasts of these London productions in a local theater is a real treat.

I was particularly interested in the play version of “The Curious Incident of the Dog in the Night-Time,” created (by another writer, Simon Stephens) from Mark Haddon’s best-selling book. I had read the book and enjoyed it greatly. And I didn’t see how it could be made into play very effectively. The book is told from the point of view of an autistic teenager, using his own highly idiosyncratic style and filled with drawings and graphics in his style. How the hell do you do that on the stage?

Well, for starters, while the book has an uncommon variety of appearances on the page, Christopher is individual only through his words and his graphics. On the stage, he can be portrayed by someone with a characteristic tone of voice and physical mannerisms. The opportunity to express these comes from the work of the novelist and the playwright, but without the brilliant work of actor Luke Treadaway they would have only been potentials. Treadaway realizes Christopher’s character, with his limitations and his strengths, in an extremely vivid manner.

And all the actors, some of whom play several parts, were excellent in this production. But the playwright, and the designers, also decided to use a very plain set and enliven and elaborate constantly with projections, graphics, and sound effects (sometimes deafeningly loud, apparently to convey the way sound impinges on Christopher’s psyche).

This was all very vivid and had a powerful impact even at the remove of seeing it projected on a screen. But, at intermission, I found myself wondering, why the hell didn’t they just make it into a movie? There are so many cinematic devices being used in this production that perhaps the producers should have gone all the way and put the frightening scenes on the train and in the railroad stations into real trains and stations and filmed it. At that point, my friend Lee pointed out that in the theater we have the physical presence of the actors, which came across even in the broadcast. In a movie, we know nobody is actually there.

I am not quite as naive as this may sound. I do know that even in the 18th century there were elaborate mechanisms for special effects in theaters. And I know about the elaborate settings of Broadway musicals (which can cost as much to produce as a movie). I’ve also seen the Metropolitan Opera’s multi-media Wagner Ring cycle. I just don’t associate such doings with “serious” theater. So maybe I am naive after all.

Without Treadaway’s physical presence, I don’t know if this play would have worked. It could easily have dissolved into a collection of special effects without a center. When I first saw “Amadeus” on the stage in London, almost 30 years ago, I had some of that feeling. The special effects, very original at that time, seemed to take over the theatrical experience. I liked the film version better. In this case, I know a movie would be quite a different experience. I suspect it might be an inferior one.

And in a film you would not have been able to enjoy the virtuoso “encore” (taken straight from the book,) in which Christopher, having postponed giving the audience an elaborate mathematical explanation earlier in the play, gets his chance to do that after the story is over. I don’t know how the hell Treadaway managed to memorize that scene, but it was dazzling.

Recently at Maverick Concerts the Music Director, Alexander Platt, introduced Ravel’s “Gaspard de la Nuit” and mentioned that Ravel was a “great virtuoso pianist.” This is a common idea but it’s wrong, interestingly wrong.

According to the accounts I have read, Ravel was not a particularly devoted piano student during his conservatory years. What efforts he did extend were mostly towards developing his compositional technique, which remained a lifelong obsession. “My objective,” he once wrote, “is technical perfection. I can strive unceasingly to this end, since I am certain of never being able to attain it. The important thing is to get nearer to it all the time.” Ravel also made unusually detailed studies of the capacities and qualities of musical instruments, which resulted in his becoming a great master orchestrator.

Ravel became merely a competent pianist. He was unwilling to put in the endless hours of practice that would have made him a virtuoso, and we are all the better for that. Certainly it would be useful and inspiring to have recordings of Ravel playing his own piano masterpieces–if he could have played them well. But he couldn’t. He rarely if ever played them in public, and he never played his piano concertos.

Ravel is not the only composer who was unable to play his own compositions. Henry Cowell’s widow once told me that her husband did OK with his avant-garde piano pieces (some of which he recorded successfully) because they weren’t very difficult to play. But he couldn’t play the piano part of his Violin Sonata when it was recorded. There are many stories about how Robert Schumann ruined a potential career as a virtuoso when he damaged his hand using a machine intended to increase the independence of his fingers. But Schumann had never been a serious piano student and never planned on a virtuoso’s career.

In all of these cases, the composers understood the technique of the piano well enough to write in innovative and imaginative ways for it. I can sympathize with how this works. In my own piano playing days, I would sometimes read through such demanding pieces as Prokofiev’s Toccata or Brahms’s arrangement of the Bach Chaconne for left hand alone. I couldn’t have played these pieces if I had practiced them for years. But I was able to learn how they worked.

During Ravel’s lifetime there was enough demand for his music so that recordings by the composer would have sold well. This demand led to two instances I know of in which recordings were deliberately and fraudulently presented as Ravel’s own when they were not. Ravel’s only recordings as a pianist were as accompanist for the singer Madeleine Grey. He never made records of his solo piano works. He did make some piano rolls, a medium in which mistakes were easy to correct. But the pianist Gaby Casadesus admitted years after the fact that when the more difficult Ravel pieces were recorded on piano rolls her husband Robert had done the playing, and the Duo-Art company issued them under Ravel’s name.

Ravel wasn’t a very accomplished conductor, either. He made only two recordings as conductor, and they are valuable for their musical insights. (More on this in a moment.) But when the French branch of HMV recorded his Piano Concerto, with the pianist for whom he had written it (the wonderful Marguerite Long), they hired the Portuguese conductor Pedro de Freitas Branco to conduct the pick-up orchestra and put Ravel’s name on the records as conductor. The deception was uncovered many years later, in the company’s archives. (Freitas Branco was credited as the conductor of the “filler” on side 6 of the 78 rpm set.)

So what is the value of Ravel’s recordings? Obviously, the atmosphere in the song recordings is authentic, and Grey was a superb singer. One of the recordings of Ravel conducting, his “Introduction and Allegro,” is an acoustical recording, made in England in 1923. Its fidelity is limited, and the English musicians involved were probably not very familiar with the music or the style, so it’s not a great experience.

However, Ravel’s other recording, “Boléro,” made in 1930 with the Lamoureux Orchestra, is a revelation. Technically, it’s not very accomplished. Although the orchestra was one of France’s best, it doesn’t play with fine precision, probably due to the limitations of the conductor. But the musical interpretation shows us what Ravel intended in his repetitious work, and it’s not as boring as it usually sounds. Ravel was famously quoted as saying, “There is no music in it.” But the slow tempo he takes allows the scoring to sound in a most convincing way, and the inflections he draws from the solo instrumentalists are fascinating. Apparently the conductor Riccardo Muti feels the same way I do, because his EMI CD of “Bolero” is a close copy of Ravel’s interpretation.

Obviously a composer doesn’t have to be able to play or conduct all of his or her own music. That doesn’t take anything away from the music, of course. I do love to hear composer-virtuosi, like Rachmaninov, Prokofiev, Sarasate, Leon Kirchner, and others, performing their own works. But I’ll never hear Bach perform and I still love his music.