This short memoir was written by my wife, Tara McCarthy, about 1989. It’s a beautiful example of her creativity.

During a Wartime summer, my father made the mistake of moving us from our real home–a small green village of New York–to the gunmetal-gray city of Akron, where he went to work for a giant rubber-tire factory.

The Akron street was not a proper street at all: it was enormously wide and marked off this side from that side as definitively as a state border drawn on a map. The stern brick houses opposite us looked miles away. To find someone to play with, I could no longer dash across a little road or sit humming on the lawn, my jacks in a drawstring bag, bouncing a rubber ball nonchalantly to tempt a passing friend into a game. No, Akron was different: your mother had to call up the neighbor to find out whether it was convenient for the children to play, and then your mother had to talk you across the street and then you had to call your mother when you were ready to come home so that she could come over and walk you back again. My mother could not do any of this walking, because her left leg was in a cast, so I could not even get across the street to check out likely-looking jacks aficionados.

Photographs of our time in Akron show me with as tragic a face as a well-fed six-year-old can muster. I was, I felt, in a prison, with only my invalid parent and my little sister and my great-aunt Inez and a maid named Jello for company. My dog had deserted me, dying on the sofa of the Pullman roomette as we crossed some dismal farmland on the way West.

My mother had broken her leg back in New York, slipping on the ice while walking my dog at dawn. “I was walking Honeybunch’s sweet little Mickey,” my mother said to my father’s new friends as she looked at me wistfully. “I almost lost my leg, didn’t I, Dan?”

“Yes, she almost lost her leg,” my father agreed. “She was very brave to make this trip.”

“I did it for Dan,” my mother said. “This was such an opportunity for him. I couldn’t let something like almost losing my leg stand in the way of his work, or of the War Ever.”

It was in almost losing her leg that my mother had acquired Jello and conjured up Aunt Inez from remote towns hear her childhood home in North Carolina. They were to be our helpers, allied forces moved in to succor the wounded and take over the battle of running the house. And tattered troops they were! Jello was sixteen years old and so terrified by the city that she had to be cajoled into leaving the house even to empty the garbage. She wept constantly over a soldier named Francis who was fighting in Europe. Jello wept as she washed the stairs, wept as she made lunch, and wept as she showed me photos of Francis. Aunt Inez was in her eighties. She wore live birds in her hair–her parakeets Sweetie and Sillabub. She had, my mother explained, very kindly agreed to act as our housekeeper, a job which consisted mainly of ordering groceries over the phone.

“Yankees are so rude!” Aunt Inez always said when she hung up. When the groceries arrived, she would once again tell Jello how to make what became the culinary staples of our brief stay in Ohio–salmon casserole, apple Brown Betty, and pineapple upside-down cake.

“We had this last night, I think,” my father would say, arriving for dinner nattily attired in his office clothes and looking handsome as usual, giving me a wink as he used to in the old days and looking pained as I pouted at him and turned away. I hated him then. He got out during the day, as he always had, and as I never did anymore. How could he move me to this dreadful place?

“I hate it here!” I usually managed to say at dinner. “There’s no one to play with!”

“Maybe your Aunt Inez could walk you across the street to meet the neighbors,” my father suggested.

“Mercy, I can’t do that!” my Aunt Inez answered. “Yankees are too abrupt! Besides, this child has her little sister to play with.”

“I hate her!” I said, watching clinically as my sister’s face turned sad.

Sweetie and Sillabub fluttered in Aunt Inez’s hair. She would say “Blood is thicker than water,” or “A bird in the hand is worth two in the bush,” then ring the little crystal bell she had brought from Down South, summoning the sobbing Jello in to clear the plates.

“Oh, my land! I don’t know what to do! I just don’t know what to do,” my mother exclaimed. “Why can’t everyone just be happy?” Little tears would well up in her eyes, perfect little tears the sight of which made even Jello pause in her weeping.

After dinner, we would all move to our special places, moving in our special ways–my mother hobbling and grimacing into the living room to listen to “Mr. Keene, Tracer of Lost Persons,” and resisting my father’s offers of assistance, saying “No, I don’t want to be a burden. Painful as this is, I’ll do it on my own, thank you1″; Jello sludging tearfully out to the kitchen; Aunt Inez fluttering after saying “Waste not, want not”; my sister running merrily upstairs, her enviable yellow ringlets bobbing, to play “Elevator” with the sliding doors in the hall or “Goodbye, Pants” with the laundry chute, so that she would inevitably get a finger smashed or a leg scraped and require the attention of the entire family before the evening was over; me stomping up to my bedroom with a volume of Uncle Wiggily held importantly under my arm; my father coming up slowly after me, in another attempt to tuck me in.

“What’s wrong with my little Zaza?” he pleaded one night. “I haven’t seen one single smile on your face since we got here.”

“I told you,” I said. “I hate it here. I want to go home. I want to go to your office, like I used to, like I used to in New York, where we live. I never get to anymore!”

“Zaza, I can’t take you to my office here,” he said. “I’d like to, but I can’t.”

“Yes, I know, it’s about the War Ever,” I said cynically. As usual, I opened Uncle Wiggily to a picture that I recognized and pretended to read. Reading was a matter of moving your eyes back and forth and making understanding faces now and then.

“It’s the war effort,” my father said. “The war effort, like in trying. Because of the War Effort, I can’t have guests in my office, not even little girls, because everything is secret. For example, Firestone makes tires for the Army.”

I pictured giant tires dropping out of planes onto Hitler’s head. “I already know about tires, Daddy,” I said indignantly.

From out in the hall there came the shriek of my sister with her thumb conveniently caught in the sliding door, and from downstairs the plaint of my mother. “Now nobody should interrupt themselves, but I am in considerable pain,” and the sound of Jello snuffling and Aunt Inez, her birds twittering, singing “Look for the Silver Lining.”

My father said, “Sometimes it is very important to the War Effort to help out at home.” He stood up and tried to look very firm. He said, “You are my best and my brightest, Zaza, and I definitely think you can help out at home a lot more than you have been doing. You could be a big help to me. Just a little smile now and then would help me.”

“I know, Daddy,” I said.

“Then why don’t you help me?” he asked.

“I don’t want to,” I said. “I just want to go home.”

“This is a very important job to me,” said my father. “It is an opportunity. Do you know what an opportunity is?”

“Yes, Daddy,” I said. I didn’t, of course. “But I don’t care.” with his big words and funny problems, he sounded just like that hapless fellow Uncle Wiggily.

We glared at one another across the shiny picture of Uncle Wiggily where Nurse Jane Fuzzy Wuzzy is helping him across something called a stile. My father left, and I listened contentedly to my sister wailing as Mercurochrome was applied to her arm. A feeling of power was washing over me as I fell asleep, a feeling that I could somehow now move my family back East to the town where I belonged, with my jacks.

How I was to accomplish this began dimly to emerge a few days later, when Aunt Inez suddenly turned off a radio program featuring Great Organ Hymns. Aunt Inez said, “Why, this is so depressing! All these songs about death! I simply cannot abide thoughts of death, can you, Jello?”

Jello stopped crying and looked at Aunt Inez quizzically. “Yes, ma’am,” said Jello. “I like hymns. I was raised with hymns. I like hymns very much.”

So at this point I enlisted Jello and the piano as my allies. I had always circled the piano warily in New York, but my parents had hauled it to Ohio anyway, perhaps in the hope that I would somehow attack music with miraculous gusto in the smoky air of Akron.

This I did do now, conscripting Jello to help me learn to play “Nearer, My God, to Thee” and “The Old Wooden Cross.” Her eyes brightened up considerably during our piano sessions.

Since Jello was about as inept as I was, the hymns took endless practice. Aunt Inez cowered in the kitchen, her birds drooping. “Why is the child always playing hymns?” she asked my father as soon as he came home from work. “I am so depressed. That child is always playing ‘Nearer, My God, to Thee.’ I can’t abide that piece. It’s about dying, and I am getting on in years, Lord knows!”

My father confronted me. “Why are you depressing your aunt with hymns about dying?” he asked.

“You wanted me to learn the piano,” I said, “and I’m learning the piano and these are the only songs Jello and I know.”

“Is that so, Jello?” said my father.

“Yes, sir,” said Jello, clear-eyed.

“Well, there it is!” said Aunt Inez. “Catering to the whims of a child and a servant! Times have changed surely!”

“Now, Aunt,” said my mother, jiggling her cast impatiently. “Now, Aunt, the child is showing some gift for music, and we have every right to be happy about that.” She fell sighing back into the chaise which my father had found for her at the same store where he had found a gas stove. An actual modern stove was hard to find during the War Ever.

The stove was supposed to be delivered on the same day that Aunt Inez and the birds were huffily scheduled to leave because of the hymns. My father was driving Auntie and the birds in their cages to the railroad depot, with Jello along just to help with Sweetie and Sillabub, after she was assured that she would not have to get out of the car until it came back to the house. “Now, Zaza,” my father said to me warily, “I am leaving it to you to look out for the delivery men. Just look out the window for them, and direct them around to the back door. Don’t have them come up the front steps, because they’re too high. This is probably the last gas stove in Ohio, because of the War Ever.”

“A stove, a real stove,” exclaimed my mother, stomping about on her cast with unusual vigor and clapping her hands as I used to do back home after a superb jacks play. “A stove just like I had back East! Thank the Lord I won’t have to feel like a pioneer lady anymore. I’m so tired of that ol’ coal stove, aren’t you, Jello?”

“Yes, Ma’am,” said Jello happily as she toted the birds out the door. I settled down to my ally, the piano, and attempted to pick out the cheery “Country Gardens.” my sister screamed from the basement that her hand was caught in the laundry chute, but my mother was too absorbed in her delight about the stove to hear her. Would my plan have a bonus? Would my sister be silenced forever in a mass of soiled linen? But her piping Shirley Temple voice yelled very soon from an upstairs window. “Men are here with something!”

I dashed to the front door. “Bring it right up here,” I hollered. “Bring it right up these front steps!”

I leaned out the window and watched with satisfied anticipation as two men edged a gigantic stove up the first of several cement steps. By step five they had, of course, lost it. The Last Gas Stove in Ohio crashed definitively down the stairs and landed with a crumped bash on its side.

“Oh, my land!” said my mother, maneuvering out onto the stoop. “That stove’ll never work now. Now you just take it back and get me a new one!”

“Can’t do it, Lady,” said one man sadly. “This was the very last stove.”

“ Oh, my Lord,” said my mother. She was literally hopping mad when my father got home from the depot. “I am up to my neck!” she told him. “I am up to my neck in this part of the world!” She tugged Jello into the kitchen, where the two of them somehow managed to construct a meat loaf and baked potatoes for dinner.

“I cannot abide Ohio,” said my mother later, vigorously slicing meat loaf. “It was bad enough I had to give up my New York frigidaire for an icebox, but now I am fated to that awful coal stove for the duration of the War. And,” she added, “it may have escaped your attention, because I have been very silent about my pain, but I have been very unhappy here.”

“Is that so?” said my father. “And how about my little Curly Top?” he said, turning to my odious little sister, with her bright smile and her millions of bandaids. Do you like it here?”

“No,” she said.

He never asked me. I don’t think he said one word to me until long after we got back home to New York. I can’t remember that he ever even told me about what my mother said was the marvelous new opportunity he had discovered back East. But I remember being sadly and smugly patient, as Nurse Jane always was until Uncle Wiggily came round.

When Jello and I were sitting in the roomette on the east-bound train, I asked her, “Is the War Ever over yet?” And she said, “I don’t know, but Francis came home. He’s down at Fort Bragg.” She smiled as she hugged me.

This essay was first published in “Woodstock Originals” in 1990, an anthology of writing by people in the Byrdcliffe Writers group. I was in the group too, although not at the same time as Tara, and I had a story in the anthology. Tara also had two poems, the only ones she ever published. I’m reviving the essay because I admire it so much and because I thought others would enjoy it, friends and strangers alike. The uncanny recall of childhood demonstrated in this essay was genuine. She often told me stories from her childhood going back as early as when she was 2 or 3.

If there are any typos, please forgive me. I had to copy it from the book.–Leslie Gerber

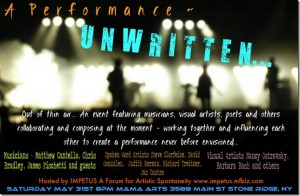

I had no hint from the announcement that an intense new love affair awaited me. It was called “A Performance Unwritten,” for an event on May 31 at a venue called MAMA Arts in Stone Ridge, New York. Its premise was that artists in various media and forms, most of whom had never worked together before, were going to create an evening of entirely improvised art. Well, no thanks, but that doesn’t sound like my bag, man…

…except that my poet friend Judith Kerman was one of the artists involved. And it was on an evening when I had nothing else planned. And it might be something that my wife, who has Alzheimer’s Disease, would enjoy, since it sounded as though it would be visually stimulating and she usually enjoys music.

When we got to Stone Ridge, my suspicions were immediately aroused by the venue. I’d never been there before, and it didn’t look like a very well-organized place. But the event attracted a fairly good-sized audience, and as soon as the trio of musicians started to play I knew I was in for an enjoyable evening, since they were quite good. As the performance progressed, some of the spoken word improvisations were involving (especially, I must say, Judy’s), some less interesting, but the music kept things lively.

And then there were the painters, one on each side of the hall. One of them was doing some pretty interesting work. The other looked at first as though she was just splashing and dabbing paint on a large black board, using several methods to get paint onto the board not including a brush. Just as I decided the work was going to be nothing but abstraction, she put her hand into white paint and pressed it down, and as she lifted it off I realized that her handprint was at the end of an arm and she was creating a figure.

That moment of recognition threw a shock into my system. I was reminded of the time, half a century ago, when I heard my first Cecil Taylor record. A jazz critic friend played it for me, telling me he thought Taylor was the next great thing in jazz. I listened with increasing puzzlement as some guy seemed to be throwing his hands at random around the piano keyboard, until I suddenly realized that an impossibly complex figure ran up and down the keyboard and was then repeated exactly. The understanding that Taylor was in complete control of everything he played forced me to listen with different ears.

I had that same realization about the work of Nancy Ostrovsky. Throughout the remainder of the performance I couldn’t take my eyes off her. After she finished the first painting, she took it off the easel, rested briefly, and then started throwing paint around again. This time, she was creating a picture of the musicians and some dancers who briefly participated in the performance.

It was art love at first sight. At the end of the performance, I rushed over to Ostrovsky and asked how much she wanted for the paintings. The price she quoted seemed quite reasonable. I handed her some money as a down payment on the one I had decided I wanted. (It turned out, not surprisingly, to be a little less than it’s costing me to frame it!)

Perhaps I should have bought the figure. It was the painting that gave me that thrill of discovery. But I decided I would have more fun looking at the musicians. I look forward to having them as companions for a long time, and to seeing a lot more of Nancy Ostrovsky’s work. When I went to her studio to collect my painting–she wouldn’t let it go immediately because she wanted it to dry properly–I saw a lot more of her work. One impressive item was a copy of a poster for a Dizzy Gillespie concert, inscribed to her by Gillespie.

My friends and I were really looking forward to the new Coen Brothers film, “Inside Llewyn Davis.” We’d all been involved with the subject matter, the early 1960s folk scene in New York, to some extent. Critics had been enthusiastic in their praise. And we were all Coen Brothers fans, most of us having seen most of their previous films.

But we all came out of the theater with scowls on our faces. None of us liked the movie very much. This was in spite of its obvious virtues: convincingly written, well acted, well directed, well photographed. So, what was wrong. Basically, none of us had wanted to spend two hours in the company of the title character, a narcissistic jerk. Try analyzing the plot of the film and you’ll see that Llewyn, a modestly talented musician, spends most of his time trying to find ways to take advantage of people–friends, lovers, other musicians, people in the music business. He starts out that way, wastes a lot of time and effort taking actions that are of no benefit to himself or anyone else (like a stupid, quixotic trip to Chicago). If some of the action or events in the story had inspired some change, some insight, some improvement in Llewyn’s character, I would have been pleased with the story. But no, he starts off a jerk and finishes a jerk too. The guy who plays Llewyn, Oscar Isaac, is distressingly convincing in his character.

(As an aside, I didn’t like most of the music in the film either. Llewyn and his friends are what I used to consider in the ‘60s fake folk musicians, people who took folk material or folk styles and sanitized it to make it more palatable to naive audiences. Peter, Paul and Mary, for example, used to make me sick. Too damn pretty. Oddly enough, Showtime broadcast a concert given in New York called “Another Day/Another Time” which was supposedly an offshoot of the film but had much better music.)

This kind of story seems to have enduring popularity with film makers and, sometimes, with audiences. Not with me. I consider it nihilism. I gain nothing from an experience like that, not entertainment, not insight, no revelations, just an opportunity to feel scornful towards some of my fellow human beings. I get enough of those reading the daily newspaper.

Another recent hit was a surprising adventure in nihilism, Woody Allen’s “Blue Jasmine.” Allen, when he hasn’t just been out for laughs, has often made remarkably powerful and moving films about our efforts to make connections with each other. “Manhattan” and “Annie Hall” were very effective depictions of people trying to make contact with others. And “Crimes and Misdemeanors,” which I consider his masterpiece, tells an ugly story in a way that invites us to understand people who act out of bad motivations without endorsing them. But “Blue Jasmine,” apparently based on Allen’s fantasy of the post-conviction life of Bernard Madoff’s wife, is a hideous little story about human defeat. Cate Blanchett does a remarkable job of portraying Jasmine. But she is a weak person whose best idea about how to cope with her personal defeat is to take drugs. Not a very good idea. Like Llewyn, she learns nothing from her situation and does nothing useful or worthwhile throughout the movie. Nothing.

I find films like this displeasing and inexplicably popular. One such movie which puzzled the hell out of me was “Thelma & Louise.” This was a story of two women friends who started off by making a spectacularly stupid and self-defeating (and unnecessary) decision, trying to hide the death of a rapist instead of reporting it to the police. They then go on a road odyssey, making the worst possible decisions at every juncture. Eventually they work themselves into such an impossible situation that they decide to escape by killing themselves, which they do in a ridiculous blaze of cinematic glory. And millions of women apparently reacted to this movie as liberating for women. Ridiculous!

I was just as displeased, and just as puzzled, by the great and continuing success of “Raging Bull. Sure, Robert DeNiro does a remarkable job of acting in this movie. But the story is about a brutish character, the real-life boxer Jake LaMotta, who starts off treating everyone around him badly and continues to do so throughout the story, ending up as bad a character as he was when he started. What am I supposed to gain from this experience? What made it even worse to me was that it’s false. LaMotta actually did change through his life and has wound up a much-beloved person in boxing circles where, in his 90s, he continues to make personal appearances and occasionally does stand-up comedy. And, by the way, the boxing scenes in this film were as ludicrously unrealistic as the scenes in the “Rocky” movies. Real boxing doesn’t look anything like that!

Incidentally, I am well aware that the kind of nihilism I’m describing is not confined to films. It’s quite popular in the theater too and has been for a long time. It’s why I avoid anything written by Harold Pinter, an ace nihilist who can write, or David Mamet, a nihilist who can’t write worth a damn. And of course nihilistic novels have been common since the 19th century.

This is not my essay in favor of being nice. I have seen, and been moved by, many extraordinary films dealing with unpleasant circumstances and ugly characters. Last year, some of my friends tried to discourage me from going to see “Amour” because they thought that seeing a film about a man trying to cope (rather badly) with his wife’s deterioration would be too disturbing to me. (I’m the chief caregiver for my wife, who has Alzheimer’s Disease.) But I was very glad I went. This film was so realistic, acted and directed with such extraordinary power, and so revealing of real human conditions, that I found it liberating to watch and I look forward to seeing it again before too long. I am not a Pollyanna. I just don’t like being invited to watch bad people acting badly and learning nothing.

When I was seventeen, I thought I should kill myself if I didn’t succeed in getting laid by the time I turned eighteen. I hadn’t had a girlfriend since I was fifteen. So I stopped spending all my spare time reading and writing science fiction, and started going places where I could meet girls.

I met Julie at a meeting of Mensa, the high-IQ society. Julie was short (an advantage to a short fellow like me), extremely attractive, and quite bright and lively, a contrast to most of the Mensans who took themselves very seriously and were generally a morose lot. She also had a pronounced British accent, which I found inexplicably enticing.

Julie shared some of my interests, including classical music, foreign films, walks in the park, even science-fiction. She accepted my invitation to see a Bergman film the following weekend. Later I spoke with a couple of the livelier guys in the club, and they told me Julie had a reputation for having Done It with more than one guy. I think they expected this to turn me off. Instead, it suggested that I wouldn’t have to convince her to Do It altogether, just to Do It with me.

We went on a few dates, all cultural events. I liked her company, and we found plenty to talk about. One of our dates was going to see a Saturday matinee of an off-Broadway play starring Jean Shepherd, the radio talker whose work we both loved. After the show, I took Julie backstage to meet Shepherd. I introduced us, saying, “Hi, Mr. Shepherd, my name is Leslie Gerber and this is my friend Julie.” Shep immediately realized what was going on, a teenager trying to impress his date, and replied, “Oh, yes, Leslie, of course. How are you doing? How are your folks?” He went on for a couple of minutes pretending he knew me. It was the finest act of spontaneous kindness I’ve ever received from a stranger, and Julie was highly impressed.

One night I brought her home to her apartment in Queens, an hour an a half away from my Brooklyn apartment. She was pleased that I was taking all that trouble, and she gave me a very tasty good night kiss.

The next weekend, we went to a party and drank a fair amount of wine. I told her about Ted’s place, a basement apartment in the Village which a bohemian friend of mine used as his writing studio. In exchange for paying a share of the rent, I had a key to the place It had a bed, although a somewhat grungy one. I invited Julie to join me at Ted’s place the following Saturday afternoon, when I had reserved time. She acted huffy about it, treating me coldly for the rest of the evening. But I still took her home, and at the door she kissed me again and said she would think about it. Thinking was hardly what I was hoping for, but I was encouraged when I spoke with her during the week and she said she was still thinking about it. Anyway, she would meet me for a movie Saturday afternoon and then we’d see. The next day I braved the embarrassment of going to a drug store to buy condoms, the brand an older friend had recommended because you could feel everything just fine with them. I even wasted one to make sure I knew how to put it on.

We met in the Village, and I told her Ted had left some interesting new jazz records at the apartment. We went straight there, and as soon as I had put a record on, Julie took over. She removed her shirt and bra, revealing a pair of exquisite breasts, and began kissing me. I became so excited I didn’t know what to do, but she guided me, undressing me gently, turning down the lights, and even helping me on with the condom.

My friends were right. Having sex, feeling that indescribable touch, was the most wonderful sensation I had ever experienced. Julie had saved my life. It was a week and a half before my eighteenth birthday.

Afterwards, Julie lay back on the bed and looked at me, smiling. “Was this your first time?” she asked.

“Yes,” I admitted.

“Well, it was very nice.”

I carried that sweet expression of approval as a beacon through decades of adversities.

The doors to bliss remained open. Julie and I spent every weekend together. She told me that her experience had not been as extensive as I had heard; she had just had a couple of lovers for brief periods. Ours was her first real “relationship.”

Often we went to Ted’s apartment. If one of our apartments became available, so much the better. We spent as much time as before talking, going to movies and concerts together, helping each other with our college homework.

I didn’t show any of the symptoms I later learned as meaning one was “in love,” lying awake nights, having trouble concentrating on anything else, needing to feel like I was constantly in touch. Those unpleasant sensations came later. Life with Julie was idyllic. I thought about life after college, and whether I could settle down with Julie in an apartment of our own in the Village.

One afternoon, we had what started off as a particularly wonderful encounter. Julie’s parents were both off at work for the day. She called me in the morning and invited me to come out to her apartment for the afternoon. I was there by noon. I had brought lunch, and we sat eating quietly, without much to say for the moment. Then she took me into the bedroom, and we had our usual passionate encounter, which, if anything, seemed even sweeter than usual.

As I lay beside Julie, floating in post-coital bliss, she suddenly got out of bed and got dressed. Then she said, “I want you to leave.”

“Why?” I asked. “Is something wrong?”

“You bet there is. I never want to see you again. You’re horrible.”

“But why, Julie? I haven’t done anything wrong.”

“Yes you have. You’re a monster. I never want to see you again. You’re a monster!”

I asked what was bothering her. All she had to say was that I was a monster and she never wanted to see me again. I gave up and left.

I was certain we could talk things out on the phone, but I was wrong. That evening, her mother, who liked me, said that Julie couldn’t talk to me. I waited a day and called in the afternoon. When Julie heard my voice, she said, “Don’t keep calling me. I never want to see you again. You’re a horrible monster.”

“But Julie, what did I do? I really don’t understand.”

“Oh, yes you do. You know what you did. You’re a monster!”

I tried calling a few more times, but she wouldn’t speak to me. I knew where I could find her, so I went to the next Mensa meeting. She was there, as beautiful and appealing as ever. When she saw me, she said, “I was afraid you would come. Get away from me, you monster.”

“Won’t you at least explain what you’re so angry about? I really don’t understand.”

“Of course you do. You’re horrible. You know what you did. Leave me alone.” She wouldn’t say anything else.

We had a mutual friend in Mensa, the red-haired siren Marilyn who later got me under her spell and then broke my heart. I enlisted her aid in finding out why Julie was so angry with me. Julie wouldn’t explain anything to Marilyn either.

Julie was out of my life. I even stopped going to Mensa because it hurt me so to see her, laughing and talking and acting as if I didn’t exist.

Decades passed. I fell for Marilyn and suffered when she eloped with her psychiatrist. I married and raised children. One of my best friends killed himself. I left New York and settled in the country, more than a hundred miles away, where I could see the stars at night. I was divorced, and didn’t see my children for a couple of years.

One day, I got a call from Marilyn. She too was divorced, and she had found herself thinking about me. We met for lunch at the Metropolitan Museum of Art restaurant, where the food is almost as impressive as the surroundings, and we talked for hours. She told me about green light meditation and her delight in her ten-year-old daughter, and about what a perfect bastard her ex-husband had been, that shrink she had left me for.

She said that Julie had asked about me a couple of times. She was married and living in Maryland, managing the real estate affairs of a recreational complex. Marilyn thought that Julie’s husband was rather aimless and dependent. I thought how sad it was that her wild spirit sounded so tamed these days, but then, who was I to talk, no Dostoyevsky as I had dreamed of being in college but a small business owner instead. Marilyn asked if it would be all right to tell Julie how to get in touch with me, and I said I would be delighted to hear from her.

Two days later I received a call from Julie. It was the middle of summer, and she said if I were interested it would be the perfect time to visit. A friend of mine, a concert pianist, was giving a performance near her home in a few weeks. We agreed that I would come for a visit then, and that we would surprise my friend by showing up at his concert.

I wondered if I would even recognize Julie. But when I arrived at her home after a day-long drive, she seemed hardly to have aged. Her accent and her bouncy spirits were intact. She brought me inside her modest house and introduced me to her husband, who reminded me of a cartoon beagle, friendly but lacking in energy or conversation. He and I exchanged very few words that evening, or during the three days of my visit. Julie took up the slack, full of enthusiastic talk about her surroundings and her work. I was tired from the trip and went to bed early.

The next morning Julie took me to see her development. She even made a few gestures towards interesting me in buying or renting a place, although the age of my car probably made it obvious that I was in no position to take on a second house. We all had dinner together and went to see a movie. Her husband again said hardly anything.

On my last day there, we went back to Julie’s development and I watched her bustle about, then retired to a cabin and read a book until the end of her day. Back at her house, she changed her outfit. I took her out for dinner. Her choice was a mediocre Chinese restaurant, which she picked because she rarely had the chance to eat Chinese food. Then we went to the concert, at which my friend played as splendidly as always. I was pleased to notice that Julie appreciated his playing.

It was past midnight when we got back to the house. Julie’s husband was asleep. She took out a bottle of red wine, and we sat at the kitchen table, sipping wine and talking. Julie told me she was still devoted to her husband, but she despaired of his ever succeeding at anything beyond his modest work. They had no children and were not likely to have any. She sounded miserable. I was feeling the impact of my failures in life and love, and I told her frankly about them.

Sunlight was hinting outside when we started making our parting gestures. But curiosity finally overcame my reticence, and I told her, “Julie, there’s one thing I’ve always wanted to know from you. When you broke off with me, you suddenly got very angry with me.”

“I did?”

“You said I was a horrible monster. You said I knew what I had done, but I swear to you, I really didn’t. It would set my mind at ease if you would tell me what I did to make you angry.”

“Heavens,” she said with a perplexed look. “I’m happy to tell you anything, but I swear, I haven’t a clue.”

(Note: This memoir is as accurate as memory permits, but a few details have been deliberately altered to protect the innocent.)

The story of my last decade is mostly the story of my wife Tara’s illness. In 2003, after a couple of months of mysterious symptoms, Tara was diagnosed with ovarian cancer and had a hysterectomy. The cancer was very early, stage 1C, and the surgeon told us that many doctors would not have recommended any follow-up treatment. He strongly advocated chemotherapy and talked us into it.

Halfway through her course of chemo, which lasted 4 months, Tara started having trouble writing (her profession for almost 50 years!) and with short-term memory. About that time the surgeon left his position at the hospital and Tara was sent to another hospital to complete her chemo, where she received no supervision and almost no attention. When she complained about the memory problems, she was told she probably had chemo-brain and it would eventually go away by itself.

It didn’t go away. After five years of attempted treatments and diagnoses, we finally wound up at Columbia-Presbyterian in New York, where a neurologist specializing in memory disorders sent her for some high-tech tests. When he showed us the results, they demonstrated extensive brain damage. He theorized it had been caused by an opportunistic infection suffered while the chemo was suppressing her immune system. There was no possible cure or treatment, he said.

She was still able to care for herself to some extent, and when my father was dying in February 2008 I was able to travel to Albuquerque for a few days. But her continuing difficulties forced me to close down my mail order business in October, 2008, and to sell the house I was using to run the business out of. I’ve only been able to do small amounts of part-time work since then. I still publish a few CDs (one DVD), sell some used CDs through Amazon, and do a little writing including my Woodstock Times column, now ongoing for more than 35 years.

During 2008, I learned of a treatment called neurofeedback which was offered by Dr. Steve Larsen in Tillson. I took Tara to him twice weekly for eight months, and she had a brief period of serious improvement. A neurologist she saw both before and after the treatments started said he had never seen such remarkable improvement in someone with her condition in so short a time. But by the end of the year the treatments had stopped working and we ended them.

We had another try with Larsen in 2010 combined with a woman he recommended named Barbara Dean Schacker, who has developed some effective treatments for stroke recovery. We tried them because strokes cause similar damage to what Tara had suffered. They had some beneficial effects too. We also went for some months to a speech pathologist for something called cognitive therapy. Both of these caused some short-term minor improvements, but they each stopped having any effect. By the beginning of 2012, in consultation with all the therapists involved, I decided to stop all treatments, all of which Tara had come to dislike, and simply focus on her comfort.

I had started writing poetry in 1999, as a result of a series of nightmares. I’m still not sure why they inspired me to write poems, a completely new activity for me unless you count the song lyrics I wrote in the ’80s. (I don’t.) But I had some success, and a lot of encouragement from Tara and from a wonderful local poet named J.J. Clarke, who took me under his wing because he’d enjoyed my radio programs.

I worked on poetry as a kind of mildly gifted amateur for several years, but then got more serious about that activity after I got to take two brief workshops at Omega Institute with Sharon Olds, one of my poetic idols. Olds was very encouraging and advised me to get into the local poetry community, which I have succeeded in doing. I’m now a regular at most of the local open mics and often a feature. I belong to a working group we call the Goat Hill Poets, which meets monthly to critique each others’ work. We’ve performed as a group several times. I’ve had some publications, planning to submit a lot more work, and I now have a daily work schedule which I keep up most of the time. In July, I will be taking a 12 day workshop with Billy Collins, who is probably aside from Olds the poet I would most like to work with. (Olds isn’t doing workshops any more, alas.)

Caring for Tara, who has now deteriorated to the point where she can’t remember my name or tell you hers, has probably been the most difficult task of my life, despite my having cared for my two dying children decades ago. It’s a lot more exhausting than it is ennobling. But there is at least some satisfaction in knowing that I am providing for this splendid woman the care she needs after more than two decades of the way she glorified my life. And I’m arranging for more time to myself so that I can write and do other satisfying things.

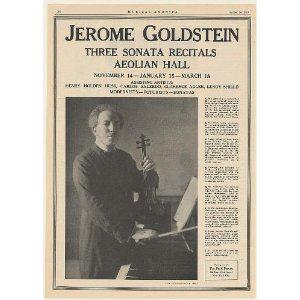

When I was a young man, I became friends with an elderly violinist named Jerome Goldstein, a customer at the bookstore where I worked. I never had the curiosity to discover his distinguished background.

In 1964 I dropped out of Brooklyn College and married a whole family, a woman with three children. In order to support us, I took a job at the Strand Book Store in Manhattan, which was then probably the largest used book store in New York if not the whole U.S. While far from its present total of two and a half million books, it was already large enough to require a full-time book cataloguer, which I became. I worked there for five and a half years before moving to Ulster County in 1970, where I still live.

Any book store buying entire collections is going to wind up with nearly valueless books. The Strand disposed of these on outdoor stands. Several times I encountered an elderly man going through the 10 and 25 cent books with great diligence, and we got to talking. When he found out I was interested in music, he told me he was a professional violinist. His name was Jerome Goldstein.

I usually left work as soon as possible to get home to my wife and family. But Jerome started inviting me to visit him, and eventually I put aside an evening for the visit. He lived in a huge rent-controlled loft, just around the corner from the Strand, on Fourth Avenue. On that first visit I met Jerome’s wife, who seemed to be perpetually angry, and saw the pseudo-splendor in which he lived. The walls were crowded with book shelves and music shelves. A somewhat deteriorated grand piano was almost hidden by piles of tattered books and papers.

When I left that evening, Jerome gave me a pie in a box and told me to take it home to my family. I was suspicious of it, and when I got home I made sure to open it after the kids had gone to bed. It was moldy, probably given to him by a bakery near the end of its expected lifespan.

Jerome told me he had played with the Philadelphia Orchestra when Stokowski was the music director. I figured it was probably true, and it was; the orchestra’s website lists a violinist named Jerome Goldstein who was a member from 1917 until 1921. But he seemed like such a crackpot, although a likeable one, that I found it hard to take him very seriously.

One day he invited me to join one of his evening musicales. I had admitted to him that I played the piano but insisted that I wasn’t very good at it (the truth) and that I had neither the technique nor the experience to play chamber music. But I did mention that I played the first Prelude from Bach’s “The Well-Tempered Clavier,” so he told me to come and play that and that he would play the “Ave Maria” melody that Gounod had fitted to the Bach Prelude.

I don’t remember that we had any rehearsal. When I arrived at Jerome’s apartment that evening, I was surprised to find a rather large audience assembled, at least 50 people. Jerome played some unaccompanied violin music first, and as I expected he didn’t sound at all good. Whatever violin he had played in Philadelphia must have been long gone, and the scratchy sound he drew from his cheap fiddle was hard to take. I suffered through the Bach-Gounod, which I didn’t like anyway.

I continued to see Jerome for another year or two, until he became ill with lung cancer. I visited him in the hospital near the end of his life, and brought away an image which comes back to me whenever I see someone smoking. He was lying in bed, feeble and incoherent, until he thought he saw demons coming at him through the walls. Then he sat up and started screaming at them.

After I left New York, I hardly thought about Jerome until one day when I was looking through a book on Charles Ives and was startled to see a photo of Jerome. The caption indicated that he had been involved in early performances of Ives’s music, sometimes with the composer at the piano. (As his private recordings reveal, Ives was a virtuoso pianist.)

The photo above is from an ad for a series of three morning recitals, with pianist Rex Tilson, given at Aeolian Hall (the place where the “Rhapsody in Blue” was first performed) in 1924. An unsigned review of the last concert, published in the New York Herald Tribune, mentions performances of works by Ives, Milhaud, and Pizzetti, giving “the palm to Pizzetti.” The Ives work was the Fourth Violin Sonata, composed in 1909 and not published until 1951. This was its premiere performance.

The Ives book also mentioned that Jerome had performed with Béla Bartók during the composer’s first tour of the United States in 1926. Doing some quick Internet research I turned up only one other reference to Jerome. He played Henry Cowell’s “Solo for Violin” (with pianist Imre Weisshaus) at a concert of the Pan American Association of Composers at “Carnegie Chamber Hall” (probably the small theater now known as Weill Hall) on April 21, 1930.

I’m sure Jerome was involved in many other interesting events like these. And I wish my callow younger self had had the sense to ask him about his career. I never did.

In the late 1970s and early ‘80s, I used to make regular trips from Woodstock to Boston. My girlfriend’s son Greg was attending the New England Conservatory of Music; he’s now a professional guitarist and teacher. I would use his trips to and from Boston as occasions to make buying trips for my classical LP business.

There were many used record stores in Boston, the ultimate college town. (I believe it still has the largest undergraduate population of any city in the U.S.) I got to know most of them, and I set up priorities. Typically, Greg and I would travel up to Boston together. I would drop him off at N.E.C., book a motel room, and go to work.

I would plan my store visits based on the likelihood of finding worthwhile records and on the stores’ schedules, usually ending at one (Zoundz, as I remember) which was open until midnight. Then I’d get some sleep, be at some store when it opened the following morning, shop until I ran out of stores or time, and head for home. When Greg was heading home, I would take off from Woodstock early, shop all day and the following morning and afternoon, and then pick him up.

Some vivid experiences from those days remain with me. When I had available time, for example, I would have dinner at the No Name Restaurant, on the Fish Pier in Boston. In those days it served fabulous seafood in unpretentious surroundings at very low prices. When I didn’t have time for that, there was another good seafood restaurant in Cambridge, the name of which I don’t remember, which was on the same block as a used record store I frequented. Parking around Boston is difficult so making two stops with only one parking spot to find was a bonus. Occasionally I even had time to hear music, once a Boston Symphony concert.

I remember following the histories of some of the record stores. Sometimes they would become more popular, start increasing their prices, and fail. In one case I wound up buying out the classical stock of a store which followed that progression. Others failed because they failed to date and weed their stock, a procedure I learned and followed when I opened my own used LP department in a local used book store. An Internet search reveals that two of the stores I visited regularly, Cheapo Records and Looney Tunes, are still in business.

For some reason, when I think of trips to Boston, my outstanding memory is of the Claverack Diner. Boston to Woodstock is a 200 mile trip, and when I left Boston by myself at 10 p.m. or later I had a hard time getting home in one piece. There was always coffee available at all the rest stops on the Massachusetts Turnpike and the New York Thruway, but driving those roads was so unchallenging that I was always afraid of falling asleep near the end of the trip. So, nearing the end of the trip, I would leave the Mass Pike, cut south on the Taconic Parkway, and then head west on Route 23, meeting up with the Thruway only about 30 miles from my exit at Saugerties.

The Claverack Diner was at a location on Route 23 which was hardly a major traffic crossroads. Yet it was open 24 hours. As I drove my last hour on the Mass Pike, I would be thinking of the Claverack Diner, its harsh-tasting hot coffee, and its fresh-baked pies. A big shot of sugar and caffeine would propel me homeward for the rest of the trip, feeling better than I had most of the way. As diners go, I don’t think there was anything special about the Claverack Diner. But it was an occasional haven for me and I was always grateful to see it.

These days I travel Route 23 occasionally, heading for the Rodgers Book Barn in Hillsdale or for Tanglewood. When I pass by the building that once housed the Claverack Diner, I feel a little pang. The Diner closed down many years ago. The last time I saw the building in use it was a flower shop, and I think that’s closed now also. So is the business I was feeding when I stopped at the Diner.

To me, it was a straightforward enough encounter. The man I was facing had been menacing and stalking a friend of mine. Now he was menacing me. But I didn’t hit him.

I learned only recently that a poet who has become a friend of mine–I’ll call her V–had been the victim of a drunken and demented man who was trying to force his way into her life. He had been calling her repeatedly in the middle of the night, showing up in her neighborhood, and in a variety of ways carrying out the traditional perversions we’ve come to label stalking. Since he is such a dodgy character I’ll call him Dodge.

Although this had been going on for months, V told me about it only recently, and didn’t want to tell the whole story. She didn’t know at that point about my experience, for almost two decades, as a volunteer with the Ulster County Crime Victims Assistance Program. During that time I had spent too many hours assisting and consoling women who had been victims of domestic violence and rape.

That experience had given me some limited special expertise in dealing with characters like her stalker. It had also trained me not to be domineering. When a woman is dealing with a man who is attempting to take her power away from her, the last thing you want to do is try to force your decisions on her, which also takes her power away. It doesn’t matter whether I like her choices or not. At least she is making them herself. I made some suggestions and didn’t press the matter.

Before long, V decided to go to the police. They are now actively investigating the case. I am hopeful there will be legal action soon. But Dodge continued to show up at the regular Monday night poetry readings at Club Harmony in Woodstock. Last month, he read a poem which included V’s name. At that point I didn’t know the stalker’s identity. “Did I just find out something I’d rather not know?” I asked V. She nodded.

A week ago, V was absent from the regular reading. I called to find out if she was OK. She was, she said, but she had her grand-daughter visiting and didn’t want to expose her to Dodge. I discussed this issue with several of the male poets who are regulars at these readings, and we decided to form a posse and tell Dodge to get the hell out and not come back.

Last night, Dodge showed up. Michael, who runs the reading, asked him to come outside to talk with us. Two more of us joined them. Michael told Dodge, very politely I thought, that his presence had become a detriment to our gatherings and that he shouldn’t come anymore. “Oh, that’s nothing,” said Dodge belligerently. “This is my last week here anyway.” I realized he was trying to take control of the situation, pretending that he was in charge. So I stepped in with my own belligerence and told him that we didn’t want him to show his face again, and why. I wasn’t polite but I didn’t threaten anything.

Dodge raised the ante. “What are you going to do about it, you fat little fuck?” he shouted at me, walking right up to me and executing the traditional threatening chest bump. “I can wipe the floor with you,” he continued.

It was the chance of a lifetime. I realized instantly that he had put himself in a very vulnerable position. The others were already moving to pull him off me, but I could have executed a quick knee to the balls and disabled Dodge immediately. And I would have had witnesses that he had assaulted me first. (That’s what assault means, by the way. The phrase “assault and battery” isn’t redundant, as I once thought. The assault part is menacing, battery actually striking.)

But I remembered V’s request that there be no violence. I let the others pull Dodge away and did nothing further.

When the reading started, he got up first (he had signed up first) and read a ranting, shouting diatribe about love. Then he left. I sat at my table, eating ice cream, my hand shaking so badly I had trouble controlling the spoon.

I’m sure I’ll always regret missing the opportunity to strike out against this awful excuse for a human being. Instead, my worst attack was verbal: “See you in jail.” I guess I did the right thing. Being a Guy, though, I’m still kind of sorry.

This morning my wife Tara woke up crying, as usual. I asked her what is wrong. Some mornings she says, “I’m so mad at myself.” Others, like this morning, she just says, “I’m having a hard time.”

I know what to do at this point. I put my arm around her. I reminded her that we set out her clothing last night, and I promised that I would help her get dressed. This usually calms her down, as it did this morning. But she wanted to jump out of bed and get started immediately, so I couldn’t indulge my inclination to lounge around in bed a bit and wake up gradually.

I soon discovered that after we had set her clothing out last night, she had taken her necklaces–an essential part of the wardrobe–off the night table where they usually spend the night and put them on top of a skirt. I had to put the necklaces back on the night table so they wouldn’t be dropped or scrambled. Next I reminded her to take off her nightshirt before putting on the nice pink tee shirt I had selected for her last night. Usually it’s an undershirt but today we are expecting a high of 84 so it will be her only shirt.

Next I reminded her to take off her night pants, pyjama bottoms I got for her when she began to refuse to take off her underpants at night. I figured it for a security issue and the pyjama bottoms do keep her content at night. After they were off, I gave her underpants, quietly grabbing the extra pair she had set out on the large dog crate which she uses as her staging area for clothing. One of the dogs used to spend most of his nights in the crate, but he has since shifted to the bed.

I had left only the dress Tara wore yesterday on the crate, but while I was getting undressed in my room upstairs she got out two skirts and left them on the crate. I’ve learned that if I take extra skirts and put them away at night she gets very angry with me, so I had left them there. This morning I helped her select one of the skirts, then put away the other one and the dress despite her protests that she needed them. I assured her she didn’t.

Next we got the necklaces to put on, and I reminded her to put on her shoes and socks. Because she started last year putting her fresh socks inside her shoes, I do the same thing. Putting on shoes and socks isn’t usually a problem, but this morning she tried to cram her feet into the shoes with the socks still inside them. I had to show her how to take the socks out of the shoes, put them onto her feet–surprisingly, I had to do this once for each sock–and then she put on the shoes.

Recently she has been putting her foot into the shoe and then raising her foot, guiding the foot into the shoe with her hand and making sure the back of the shoe doesn’t get stuffed down inside. I first discovered this could be a problem about a year ago. One night she was getting undressed and when she took off one sock I could see her heel had been bleeding. Apparently she never noticed the discomfort. Sometimes I try to guide her into pulling the backs of the shoes back up, but this morning I didn’t want to be bothered so I just did that job myself.

After all this was finished, and during just a few seconds when I took my eye off her, Tara took her nightshirt and put it back on over her day clothing. She resisted taking it off, saying she needed it, but I managed to persuade her gently that it didn’t go with the rest of her outfit.

Tara and I walked into the kitchen, where she usually waits for me to get dressed and where I grab my small cup of coffee to sip while I’m dressing. (I set up the automatic coffee maker every night if I remember.) She called the dogs to follow her but, as usual, they didn’t come. I assured her they would come when we were ready to go out, and I went upstairs to my room where I usually get dressed while watching a few minutes of “Morning Joe.”

When I got back downstairs, the dogs had come out from the bedroom and were keeping Tara company in the kitchen. She had taken their collars out of the breadbox where we keep them, but she hadn’t put them on the dogs. Sometimes I lead her through this process but this morning I did it myself. Next she took the two dog leashes and asked if she should put them on the dogs. I told her we didn’t use them on neighborhood walks except at night, but that she should bring one with us in case Fluffy decided, as she sometimes does, to just sit down halfway through the walk. I also sprayed both of us with bug repellent, Tara complaining as always. I’ve stopped trying to explain to her about mosquito bites because she doesn’t understand what they are although she does scratch at them.

Our walk was uneventful, and so was breakfast. As always I fed the dogs first, then got to work making our breakfast, this morning turkey breakfast sausage and scrambled eggs. I put on our morning music, usually in recent days boogie-woogie, which Tara likes very much these days, but this morning Haydn Piano Sonatas. While I was cooking a friend called. We talked while I was cooking.

After breakfast we did the dishes. This includes Tara’s only remaining household chore, wiping the dishes and putting them away. Until about six months ago she did very well at this, remembering where to put a high proportion of what she wiped. These days, though, the proportion is down under 50% so I keep having to interrupt myself to show her where things go, and, once, to remind her to wipe a dish instead of putting it away still wet.

When we got near the end of the job, I washed and handed her a pancake flipper I had used in making the sausage and eggs. I showed her where it went into the lazy susan, but she couldn’t get it in because she was holding it with the handle up. I showed her it had to be put in handle down, and she said, “Shut up,” sounding very angry. I must have been more keyed up than I realized because I had a surge of anger and yelled at her. I’ve been warned by a couple of psychologists that this anger is inevitable in dealing with dementia patients, who are angry themselves much of the time. But I was sorry.

We had almost an hour left before Tara’s Friday caregiver Susan showed up to take her out on her day’s excursions. Susan takes her driving, for lunch, and to the movies most Fridays. I get time off to handle what’s left of my business, to speak with friends (lunch today), and to write things like this.

Sitting in my back yard on a warm July afternoon, just enjoying the outdoorsness of it all, my reverie is interrupted by a pattern of bass notes. It sounds as though it’s coming from quite far away. Someone must be driving his car (must be a male) with the windows open, listening to bad music at incredibly loud volume. Someday he’ll have tinnitus but he probably doesn’t even know what that is.

The sounds continue for a while, perceptibly changing direction, until they finally fade out and disappear.

I immediately start to form an impression of this guy. He’s a jerk. Not only does he like bad music, he wants to force his own lack of taste on the rest of the world. He might as well have an amplified cast of his dick on the front of his car.

He obviously doesn’t care anything about the rest of the world. He eats McGreaseburgers and counts on my health insurance company to take care of him–by paying higher hospital rates than it should have to–when he shows up penniless and uninsured at the emergency room. He thinks things like organic food and conservation are stupid. Probably drinks a lot of beer, too–cheap beer, tasteless Budweiser, not Anchor Steam.

He’s one of those people who stands in the Woodstock post office, dumping his junk mail into the Waste bin and ignoring the Recycling bin a foot away. He probably has no idea of what recycling is, and if he did, he’d think it was a waste of time.

He cheats on his wife, God help her. I hope to God he doesn’t have any kids. If he does, he probably beats them.

He votes Republican, not because he approves of the party’s political philosophy, or even knows what it is. He just doesn’t like the idea of some black guy being president. If he ever met Romney at a party he’d probably wind up in a fistfight with him, but he’ll vote for him.

He likes to work just long enough so that he can get unemployment insurance, and then when it’s getting time for that to run out he starts looking for work again. He probably didn’t graduate from high school or get a GED.

He likes to shoot wild animals for excitement, and brings the corpses for someone else to cut up so he can jam them into his freezer.

….Or then, I suddenly realize, maybe he’s just some innocent teenager who likes the same music all his buddies like and wants to play it loud. Wasn’t there a time when I did that?