Recently I’ve been listening to two Russian classical pianists from very different eras. Vladimir Feltsman is still in his prime. Vladimir de Pachmann was one of the earliest pianists to make records. I love them both.

I was involved in the Vladimir Feltsman story in a small way. After he applied for an exit visa to leave the Soviet Union with his wife and son in 1979, he immediately became a “nonperson.” Not only was the application refused, but his career was shut down. He had already toured outside the Soviet bloc, but foreign booking agents were told he was not available for touring. He was forbidden to perform anywhere for two years, after which he was gradually given demeaning assignments like playing a recital in a kindergarten classroom on an upright piano at 10 a.m. His Russian LPs were suppressed and recordings of his concerts disappeared from the Soviet radio archives.

Various Western musicians took up Feltsman’s cause, without immediate results. Daniel Barenboim organized a tribute to Feltsman at Carnegie Hall, at which he and several other famous pianists performed. For the last number on the program, the spotlight was shone on the vacant piano while one of Feltsman’s recordings played.

As a fortunate byproduct of my work as a classical record dealer, I found two of Feltsman’s suppressed recordings in 1984: one original Soviet LP, the other a reissue on a Spanish cassette. (I have since obtained all of them.) At the time I was doing regular classical music broadcasts over WDST in Woodstock. I told Jerry and Sasha Gillman, owners of the station, that I had these suppressed recordings and wanted to do a special. Jerry suggested we attempt to get an interview with Feltsman. I expressed skepticism, but I should have known Jerry better. He called our local representative, Matt McHugh, who in turn got in touch with the State Department. Eventually we heard from the U.S. Ambassador to the Soviet Union, who turned out to be friendly with Feltsman. Sure enough, we got our interview, recorded off the phone from his apartment in Moscow. The resulting program went out on our station, then WQXR-FM in New York and a little later over the Voice of America.

The president of the closest major educational institution, Alice Chandler of the State University of New York at New Paltz, heard about the broadcast. The following month, she and a group of American university professors traveled to Russia to visit with “refuseniks,” people who had been refused permission to leave the U.S.S.R. Chandler met Feltsman at his apartment, and told him if he could ever leave she would offer him a job at her school. He joked with her that if she could get him a false passport he would go immediately.

He was finally allowed to leave in 1987, due to continuing intervention from our State Department and specifically the Secretary of State George Schultz. Feltsman eventually learned that he and several other refuseniks had been released in exchange for some concession by the U.S., but he never found out what that was.

I was among a group of people who met the Feltsmans when the arrived in the U.S. I remember vividly his four-year-old son Daniel running into the press room at Kennedy Airport bouncing a helium balloon on a string and yelling “Mickey! Mickey!” (It was Mickey Mouse.) I didn’t get to hear Feltsman’s first performance in the U.S., at the White House. (I did eventually get a tape of it for broadcast on WDST, the only U.S. outlet that got to run it.) I did hear his official debut at Carnegie Hall, which confirmed what the recordings had suggested: he was a major pianist, with a wide range of abilities and the versatility to play almost anything convincingly. I was particularly impressed with the way he played excerpts from Messiaen’s “20 Views of the Infant Jesus,” with such color and conviction that the audience was transported.

Over the intervening quarter of a century, I have heard Feltsman numerous times, occasionally in New York, more often at the college. Last weekend, as part of the inauguration ceremonies for the college’s new president, and to celebrate his 25th year there, Feltsman played a brief benefit recital at the college. Perhaps by accident, more likely on purpose, Feltsman invited comparisons with the great Sviatoslav Richter, whom he heard in concert many times. He played Mussorgsky’s “Pictures at an Exhibition,” one of Richter’s most famous triumphs. The two other works on the short program, by Schubert and Liszt, were pieces also included in Richter’s most famous recording of “Pictures” (from 1958 Sofia concerts).

I’ve always admired Feltsman’s playing. As a Bach player, he is simply unequalled among those I’ve heard. One of the many fine features of his Bach is his ability to add embellishments to repeated sections of the music, a necessity in Bach’s day but a rarity in ours. Little improvisations like that were expected in performances up through the time of Mozart and even beyond. We know that Chopin often varied his music when he played it. The few grace notes that Feltsman added to his Schubert Impromptu were nothing radical, but they showed the way he thinks about music–creatively.

Feltsman has never been a “black and white” pianist, as his very colorful Messiane playing demonstrated at my first hearing of him. But after hearing his Liszt and Mussorgsky, I feel he has widened his color pallette over the years. The shading in these works was actually reminiscent of Richter.

Creative interpretation was also a part of the style of Vladimir de Pachmann, who was born in 1848 and began making records in 1907. Pachmann has been one of my favorite pianists since I first heard him, more than 50 years ago, in an LP anthology of great Chopin players of the past.

It’s difficult to listen to Pachmann today. Most of the recordings are acoustical (done through a horn, before microphones came into use). They have limited frequency range and, usually, heavy amounts of surface noise. But that’s never stopped me from marveling at Pachmann’s performances, free in a way that would not be acceptable in today’s concert halls but always convincing and expressive. If I had to use one recording to exemplify eloquence and poetry in classical performance, it would probably be Pachmann’s playing of Chopin’s Nocturne in E Minor, Op. 72, No. 1. Despite the late opus number this is actually early Chopin, published posthumously, and it may not be exactly Chopin’s greatest music. But it’s the best sounding of Pachmann’s recordings, and one of the few among his last discs that shows the pianist completely in control.

You can hear that recording for free on the Internet. But if the idea of hearing romantic piano music (mostly Chopin, but also Liszt, Mendelssohn and others) played by a survivor of the romantic era appeals to you, there is a unique opportunity available now. The Marston label has issued a four-CD set of the complete surviving recordings of Pachmann, including quite a few that were never published on 78s. For years I have been dreaming of owning such a set, and now that it’s available, it has been done the way I wanted to hear it. That Chopin Nocturne, for example, should have been heard in clear, fairly wide-ranging sound. It was published on RCA Victor’s best shellac material (the so-called “Z” pressings). But all the previous reissues of it I have heard were sonically dull, filtered to remove surface noise. Marston’s edition is what I’ve always wanted. And for the asking price, it strikes me as a real bargain.

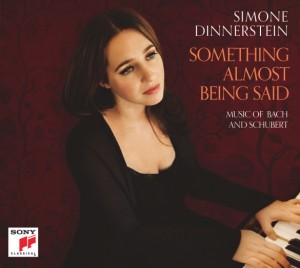

When I first heard the pianist Simone Dinnerstein, I was very favorably impressed with her playing. Perhaps that helps to explain why I have been so disappointed in her recent development.

Dinnerstein’s performances with cellist Zuill Bailey at Maverick Concerts were splendid. One time they played all of Beethoven’s Cello Sonatas in one concert. (They also recorded them for Telarc.) And at the Bard Music Festival devoted to Aaron Copland, she played Copland’s “Piano Variations” with such intensity that I was literally in tears at the conclusion. I can understand why Copland told a friend that the “Piano Variations” was his favorite among his works. Dinnerstein played it better than anyone else I’ve heard–and I’ve heard it many times–except for the composer’s own recording.

I’d actually been hearing about Dinnerstein for several years before I actually heard her play. Her father, a well-known painter, is a friend of one of my best friends, and I’d been hearing from him about Simone’s prodigious talent. Hearing her in person confirmed the reports.

So I was excited, five years ago, by the chance to hear Dinnerstein play Bach’s “Goldberg Variations” nearby, at Bard College, and I went with high expectations. I was appalled by what I heard. She seemed to have no idea of proper Bach style, frequently deviating from regular meter to make exaggerated expressive points. I don’t say that Bach playing has to be rigidly metronomical to be “correct.” But Bach is a baroque composer, not a romantic, and the power of constant rhythm is an essential aspect of his music. Dinnerstein played as if she were totally unaware of this aspect.

The performance was quickly followed by a recording, issued by Telarc. I heard it, and it was similar to the live performance I had attended. While some reviews shared my outlook, others hailed the disc as a “fresh” outlook on Bach’s music. The disc became such a best-seller (within the context of classical music sales, of course) that Dinnerstein was quickly snapped up by Sony Classical.

Dinnerstein’s third CD for Sony, entitled “Something Almost Being Said”, will be released on January 31, 2012. It represents a bit of a departure, since it’s not all Bach; it includes two Bach Partitas and also the first set of Schubert Impromptus, D. 899. Listening through it, one can tell that Dinnerstein is a well-equipped pianist. She has the dexterity and control to play demanding music in any way she wishes. And, at first, the CD, which begins with Bach’s Second Partita, sounds as though it might be a good one. Although there is some fooling about with rhythm in the opening Sinfonia, it’s still mostly well disciplined. But as the work progresses, Dinnerstein deviates more and more from strict tempo, reminding me of my reaction to a Bach performance I heard a couple of years ago. After a violinist’s rhythmically free playing of a fugue for unaccompanied violin, I wrote in a review, “Disrupting the rhythm of a Bach fugue to make a point is like interrupting sex to answer a telephone call.” It’s that disturbing. The final “Capriccio,” one of the most difficult movements in Bach’s keyboard works, is so fast it sounds hectic.

The Schubert Impromptus are no better. Dinnerstein’s tempo for the first, in C Minor, is so slow that the piece takes her 11:37 to play. By contrast, the great Artur Schnabel plays it in 8:53. For a piece of that length, 2 ½ minutes is a tremendous difference in time. And if you hear the way Dinnerstein starts to toy with the rhythm of the music at 4:25 of this movement, you may wind up as unhappy as I am.

But the worst example I can cite is Dinnerstein’s playing of the opening movement of the First Partita, played at a ludicrously slow tempo and with rhythmic freedom that would be excessive in Chopin. This is truly awful musicianship.

Dinnerstein is, alas, only the latest in a series of prominent musicians who have come to fame by playing in a manner I consider self-indulgent and unmusical. Such pianists as Ivo Pogorelich, Mikhail Pletnev, and Olli Mustonen have become great successes with performances that I doubt would have won them admission to any major music conservatory. Recently I heard a Chopin Prelude on the radio and said to my wife, “I don’t like this pianist.” It was Pogorelich. Mustonen, whose recordings had driven me crazy with their excessive rhythmic freedom, found a new way to antagonize me by recording a complete CD of Beethoven Variations and playing them with weird detachment and hyper-clear articulation.

One day I was listening to the radio and heard some unaccompanied violin music I did not recognize. It took me two minutes to realize it was the unaccompanied portion of Ravel’s “Tzigane,” music I know very well, but being played so freely it was unrecognizable. “Ah,” I said to myself, “must be Nadia Salerno-Sonnenberg.” It was. But some people like this kind of playing. Remind me not to invite them over for dinner.

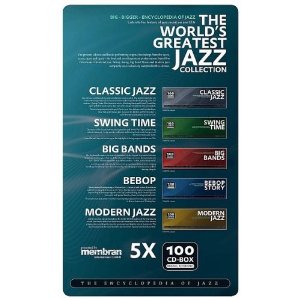

Wondering what to do with your Christmas bonus or cash gifts? I know how you can get a 500-disc series of jazz recordings for about $500.

This series, entitled “The Encylopedia of Jazz,” is probably the largest-scale recording project ever put together. Experts and collector friends I consulted couldn’t come up with anything in the past larger than the Philips “Great Pianists of the 20th Century,” 100 two-disc sets.

“The Encylopedia of Jazz” is published by Membran, a huge German conglomerate which has issued many super-bargain sets in the past. I own quite a few of its “Quadromania” boxes, four disc sets which I bought for an average of about $12. They include fine selections, mostly of jazz musicians but sometimes classical music, in quite good sound, with good documentation and even rudimentary program notes. Membran also has issued many 10-disc sets, economically packaged in small boxes with the individual discs in strong paper sleeves. These sets come with no documentation at all, just names of performers and titles. I have a wonderful Ella Fitzgerald set in this series, and a box of tango recordings most of which come from 78s. They’re delightful. I had the Miles Davis set also, but I gave it away because I was so frustrated in being unable to find out who was playing on each individual track. (Also, apparently to get around copyright laws dealing with compilations, Davis’s LPs were broken up between different CDs, making for a frustrating listening experience.)

“The Encylopedia of Jazz” was issued in 2008. This leaves me fearful that it could disappear before too long. Membran once had a 168-disc set of ragtime and early jazz, which I frequently saw on eBay. I was determined to get a copy for $100 or less, but I kept being outbid by a few dollars and never got one. Now it’s apparently out of print and being offered for $700. So, when I ran into the new series by accident on eBay, I bought the first volume, “Classic Jazz,” to check it out. The selection and sound quality were good enough so that I quickly picked up the remaining four volumes. Didn’t want them to get away.

I can’t review this series. I’m only halfway through listening to Volume 1, and some of that “listening” has been pretty casual. But I can give you a description and overview of the series.

Each boxed set has 100 CDs. The paper sleeves that hold the discs list the titles, authors, and timings. A booklet with each set has personnel listings and matrix numbers (but not labels or issue numbers). There are no program notes, but every once in a while the compiler has sneaked in a comment (like identifying Louis Armstrong’s first recorded vocal). Each set also comes with a CD-ROM listing the contents of the entire series. Many of the discs are encoded with text information which tells you the name of the set, the disc number, the title of the disc (usually the leader of the group), and the track title. This information is really useful when you’re driving. However, some discs in the first two sets (all I have investigated) lack this encoding, and a few apparently list only the track number, not its title.

Nearly all the discs are devoted to one performer or band, but in the cases of the few compilations the names of the performers are not in the texts. One of the most useful discs in “Classic Jazz” is a collection of very early recordings from New Orleans, all of which are fascinating and most of which are by performers I’ve never heard of. (They must have been recorded by mobile recording units, since there was no recording studio in New Orleans until Cosimo Metassa started his after World War II!) If you’re listening to this disc in the car, you can’t find out who is performing on each track without taking your life in your hands to look at the disc sleeve.

I know one dealer who refused to sell these sets, after they were offered to him at very low prices, because of the hazards of dealing with large sets. Here’s one example: in “Classic Jazz,” disc 58 is supposed to contain recordings by Eddie Lang and Joe Venuti. It’s properly labeled and comes in the right sleeve, but the contents of the disc is actually identical to that of disc 69, a Bix Beiderbecke collection (which also appears properly on disc 69). I wrote to Membran asking for a replacement disc but got no answer, so the error was probably never corrected. I can only imagine what this dealer would have gone through getting back the whole set because of this error and being unable to do anything about it. Also, unless you put the box in your listening room and the discs never get far from their box, there’s an excellent chance that a disc or two will stray and be missing for a while or forever. My own “Classic Jazz” disc 11 has gone missing and I’m still looking for it.

Another drawback: while these boxes aren’t gigantic for 100-disc sets, they aren’t as economical as they could have been. Instead of lining all the discs up in a row, they are presented in three mini-browsers, each allowing enough room to flip through the discs. This format makes it easy to locate a given disc, but it also means each one of the boxes take up lots more space than Brilliant Classics’ 170-disc set of the complete Mozart.

There are two peculiarities of the Encyclopedia of Jazz which may affect some potential listeners one way or the other. The first is the inclusion of alternate takes. There are many of them. The disc of the earliest Duke Ellington even has a couple that were not in the Classics label’s coverage of the same period. When I get to hear alternate takes of great soloists like Louis Armstrong or Charlie Parker, I can definitely enjoy their different responses to the same tune. But the great majority of these alternate takes don’t feature outstanding improvisors, and I find hearing almost identical versions of the same arrangement two or three times unilluminating. Also, strangely, the producers of these sets allow very little time between tracks. The industry standard is usually 5 or 6 seconds. On these discs, it’s about a second. I’ve gotten used to this but it’s still not my preference.

When I first saw the listings of these sets, I was skeptical about the sound quality. When I started listening to them, I became skeptical about their origins instead. While they aren’t the absolute ultimate in transfer work–the early King Oliver sides, for example, aren’t quite as vivid as they are in the Off the Record/Archeophone set–they are mighty damn close. I spent some time trying to figure out what label or labels Membran had gotten its material from. But several factors, including credits to collectors in the booklets coming with the later sets, have left me fairly certain that Membran has done its own transfers. How the label managed to compile this amazing collection of material–approximately 10,000 sides!–I will never understand. But it does seem that the series has been compiled and transferred from scratch. (Sorry!)

Glancing through the contents of all five sets, I am fairly impressed with the quality of the selections. The “Big Band” set was the most pleasant surprise. I was afraid it would be full of non-jazz blandness like Glenn Miller, but there’s only one Miller disc, and lots of Fletcher Henderson, Duke Ellington, and Count Basie. Some of the “Classic Jazz” discs might seem like wastes of time, and my real introduction to “Red” Nichols demonstrated why my friend Tom Piazza’s “Guide to Classic Recorded Jazz” dismisses him as “much-recorded” with no further discussion. But the Goofus Five gets two discs, 25 tracks each, and while they’re not great music they are very entertaining, perfect driving music.

There is one very major drawback to the selections. The series should have been titled, “Encyclopedia of Instrumental Jazz.” Singers appear only incidentally, if they performed with bands that are otherwise included. There are no discs devoted to Ella Fitzgerald (as I mentioned above, Membran has already issued a ten-disc set of her, so they had the material), Billie Holiday, Sarah Vaughan, or any other singers. So what did I want, a sixth set of great singers? Maybe. Also, the compilers have gone out of their way to avoid piano solos. There’s a group of Earl Hines solos on one of his discs, but the early Jelly Roll Morton collections leave out his fabulous 1923-24 solo sides completely. I haven’t noticed any solos by Fats Waller or James P. Johnson either.

While none of these sets offers comprehensive coverage of its topic, most of them are pretty thorough. I can’t think of a major artist who is omitted, although no doubt a real jazz expert could. The “Modern Jazz” set is more of a sampler than the others, including relatively small selections of some major artists. (The one disc devoted to Monk presents his album with Art Blakey and the Jazz Messengers, one of the least characteristic of his recordings and one of my least favorite.)

So, accepting all these shortcomings, do you still want to fill up about seven feet of shelf space with these boxes? I expect them to be keeping me company for the rest of my life, and I’m sure that although I’ll play through every disc in the years to come, I’ll never have enough time to absorb all the material. I’m still glad I have them. So I’m going to tell you how I recommend buying them. But let me add that you might want to keep an eye on eBay’s auction listings. As I write, used copies of all five boxes are on offer, and the high bid on each is $75, but they have only a few hours to run and will be gone by the time this posts. Still, they could show up again. For more reliable purchases, a combination of Amazon and eBay will serve you best:

Classic Jazz: available through Amazon for $81.31 (prices listed include shipping).

Big Bands: available through Amazon for $80.00

Swing Time: available through eBay for $149.99 “or best offer.” Also available new or used from amazon

Bebop Story: available through Amazon for $80.33.

Modern Jazz: available through eBay for $199.99 “or best offer,” Amazon for $165.74.

I don’t know why the “Modern Jazz” set is offered at so much higher a price. However, I tried making “best offers” on the sets I bought (from a seller in Germany, who charges no additional shipping). I got “Swing Time” for $120, “Modern Jazz” for $125. My total outlay for the entire series was just a bit over $500.

The entire set is available from amazon, under the title “The World’s Greatest Jazz Collection”