My friends and I were really looking forward to the new Coen Brothers film, “Inside Llewyn Davis.” We’d all been involved with the subject matter, the early 1960s folk scene in New York, to some extent. Critics had been enthusiastic in their praise. And we were all Coen Brothers fans, most of us having seen most of their previous films.

But we all came out of the theater with scowls on our faces. None of us liked the movie very much. This was in spite of its obvious virtues: convincingly written, well acted, well directed, well photographed. So, what was wrong. Basically, none of us had wanted to spend two hours in the company of the title character, a narcissistic jerk. Try analyzing the plot of the film and you’ll see that Llewyn, a modestly talented musician, spends most of his time trying to find ways to take advantage of people–friends, lovers, other musicians, people in the music business. He starts out that way, wastes a lot of time and effort taking actions that are of no benefit to himself or anyone else (like a stupid, quixotic trip to Chicago). If some of the action or events in the story had inspired some change, some insight, some improvement in Llewyn’s character, I would have been pleased with the story. But no, he starts off a jerk and finishes a jerk too. The guy who plays Llewyn, Oscar Isaac, is distressingly convincing in his character.

(As an aside, I didn’t like most of the music in the film either. Llewyn and his friends are what I used to consider in the ‘60s fake folk musicians, people who took folk material or folk styles and sanitized it to make it more palatable to naive audiences. Peter, Paul and Mary, for example, used to make me sick. Too damn pretty. Oddly enough, Showtime broadcast a concert given in New York called “Another Day/Another Time” which was supposedly an offshoot of the film but had much better music.)

This kind of story seems to have enduring popularity with film makers and, sometimes, with audiences. Not with me. I consider it nihilism. I gain nothing from an experience like that, not entertainment, not insight, no revelations, just an opportunity to feel scornful towards some of my fellow human beings. I get enough of those reading the daily newspaper.

Another recent hit was a surprising adventure in nihilism, Woody Allen’s “Blue Jasmine.” Allen, when he hasn’t just been out for laughs, has often made remarkably powerful and moving films about our efforts to make connections with each other. “Manhattan” and “Annie Hall” were very effective depictions of people trying to make contact with others. And “Crimes and Misdemeanors,” which I consider his masterpiece, tells an ugly story in a way that invites us to understand people who act out of bad motivations without endorsing them. But “Blue Jasmine,” apparently based on Allen’s fantasy of the post-conviction life of Bernard Madoff’s wife, is a hideous little story about human defeat. Cate Blanchett does a remarkable job of portraying Jasmine. But she is a weak person whose best idea about how to cope with her personal defeat is to take drugs. Not a very good idea. Like Llewyn, she learns nothing from her situation and does nothing useful or worthwhile throughout the movie. Nothing.

I find films like this displeasing and inexplicably popular. One such movie which puzzled the hell out of me was “Thelma & Louise.” This was a story of two women friends who started off by making a spectacularly stupid and self-defeating (and unnecessary) decision, trying to hide the death of a rapist instead of reporting it to the police. They then go on a road odyssey, making the worst possible decisions at every juncture. Eventually they work themselves into such an impossible situation that they decide to escape by killing themselves, which they do in a ridiculous blaze of cinematic glory. And millions of women apparently reacted to this movie as liberating for women. Ridiculous!

I was just as displeased, and just as puzzled, by the great and continuing success of “Raging Bull. Sure, Robert DeNiro does a remarkable job of acting in this movie. But the story is about a brutish character, the real-life boxer Jake LaMotta, who starts off treating everyone around him badly and continues to do so throughout the story, ending up as bad a character as he was when he started. What am I supposed to gain from this experience? What made it even worse to me was that it’s false. LaMotta actually did change through his life and has wound up a much-beloved person in boxing circles where, in his 90s, he continues to make personal appearances and occasionally does stand-up comedy. And, by the way, the boxing scenes in this film were as ludicrously unrealistic as the scenes in the “Rocky” movies. Real boxing doesn’t look anything like that!

Incidentally, I am well aware that the kind of nihilism I’m describing is not confined to films. It’s quite popular in the theater too and has been for a long time. It’s why I avoid anything written by Harold Pinter, an ace nihilist who can write, or David Mamet, a nihilist who can’t write worth a damn. And of course nihilistic novels have been common since the 19th century.

This is not my essay in favor of being nice. I have seen, and been moved by, many extraordinary films dealing with unpleasant circumstances and ugly characters. Last year, some of my friends tried to discourage me from going to see “Amour” because they thought that seeing a film about a man trying to cope (rather badly) with his wife’s deterioration would be too disturbing to me. (I’m the chief caregiver for my wife, who has Alzheimer’s Disease.) But I was very glad I went. This film was so realistic, acted and directed with such extraordinary power, and so revealing of real human conditions, that I found it liberating to watch and I look forward to seeing it again before too long. I am not a Pollyanna. I just don’t like being invited to watch bad people acting badly and learning nothing.

Tony Kushner (left) and husband Mark Harris

The chance to hear Tony Kushner speak again, a decade after his talk at Bard College, was too enticing to miss. Through a lucky coincidence, I also got to meet one of my few heroes.

I first became aware of Tony Kushner’s work when my wife took me to see the original Broadway production of “Angels in America.” We went to New York, checked in at the hotel we had booked for the night, ate lunch, and went to the matinee performance of Part 1. That part ends with a scene of epiphany when a man sick with AIDS is visited by an angel who proclaims him a prophet. I was so moved by that scene that I literally lost the power of speech. If Tara hadn’t been with me to guide me, I could never have found my way back to our hotel, just a few blocks from the theater.

Taking in the whole play in a single day might have been a mistake, since its impact was so overwhelming. But I’ve never forgotten the experience, which still ranks as one of the most powerful I’ve ever had, comparable to the birth of a child or the death of a parent. This might sound like an exaggeration but it’s not.

I got to experience “Angels in America” again when a filmed adaptation was broadcast over HBO. It was the kind of work that justifies the whole medium of television. I watched it on two Sunday evenings, surrounded by friends, and again was astonished by the power of this great writer. We had another showing a few years later, with similar results.

A few days before the broadcast of “Angels,” I ran into a novelist I know slightly. I asked her if she had HBO and she said she did. I told her about the coming broadcast. She said she was planning to watch the first hour, but it was running from 8 to 11 and she always went to bed at 9. I told her she would never be able to turn the TV off. She said I didn’t know her well enough. I bet her a dollar she wouldn’t be able to stop watching it. A couple of days after the broadcast I got a dollar bill in the mail.

While “Angels” remains his best-known work, Kushner is far from a one-hit wonder. Tara and I have been to see several of his other plays, including the more recent “Homebody/Kabul,” the musical “Caroline, or Change,” and the early “A Bright Room Called Day.” I’ve also read some of his excellent essays.

We got to see him in person when he was given an honorary degree by Bard College about a decade ago. The event was not, as usual, part of a college graduation but a separate event. Kushner performed in a brief one-act play, the title of which I cannot remember or locate. In it, Laura Bush, a former librarian, read a story to a group of dead Iraqui children. As usual with Kushner’s work, it was both funny and moving. Kushner, incidentally, took the part of Laura Bush. He then gave a brilliant talk, largely centered on current politics. Bard promised me a transcript, but it turned out that the talk had been completely spontaneous and Kushner had no text available.

When I received a flyer for a Kushner talk at Temple Emanuel in nearby Kingston, I immediately ordered tickets. A few days later, I ran into a woman at the Woodstock post office who was mailing out flyers with Tony Kushner in large type. I remarked to her that I had already bought tickets for the talk, but she told me that these invitations were for a “meet and greet” session earlier in the day, going out to a selected small list of people. I told her I would be interested, and she gave me one.

So it was that, through nothing but dumb luck, I got to go to the afternoon session. The admission price was $150, including the evening talk. But I don’t have many living heroes, and the event was two days after my birthday. So I gave myself a ticket as a birthday present.

The event took place at a private home in Kingston. While most of the attendees were admiring the view of the Hudson River from the back porch, or looking at the impressive artwork throughout the house, I realized I felt tired and sat down on a chair in the living room. Someone politely informed me that the chair and the one next to it were being saved for Mr. Kushner and Rinne Groff, the playwright who was going to be his conversation partner. OK, I said, and I got up and sat down in another chair right next to those two. Sure enough, Kushner and Groff arrived a few minutes later, shook a few hands, and sat down in those chairs, Kushner right next to me.

I introduced myself, thanked him for his work, and told him quickly the stories of my reaction to seeing “Angels” on Broadway and of the dollar bill. Then I explained that I ran a classical record label, and because I’d read that he loved Beethoven I had brought him some samples as a gift. “What’s your label called?” he asked. “Oh, it’s small, you won’t know it,” I said. “It’s called Parnassus.” “Don’t you have CDs by some famous pianist?” he asked. “Sviatoslav Richter,” I said. “Oh, yes,” he replied. “Those were favorites of my friend Maurice Sendak. He gave me one of them.”

After he chatted with a couple of other people, Kushner was introduced by the host of the event. Then, instead of circulating, as I had expected him to do, Kushner began a dialogue with Groff. He told some very interesting stories that were not, of course, repeated during the evening. Someone asked him how he wrote, and he showed off his antique glass fountain pen. “I like fountain pens,” he said, “because you can see the difference in the emphasis of the stroke of the pen on the paper. It shows how you were feeling when you wrote something.” He also explained that this particular pen didn’t leak or explode in pressurized airplane cabins.

As part of his work on a collected Library of America edition of Arthur Miller’s plays, Kushner met the librarian of the institution which bought Miller’s papers. The librarian told him of going to Miller’s home to help him sort through his boxes. Miller came across a batch of letters tied with a pink ribbon. “What are those doing here?” he exclaimed. “These were from Marilyn.” He immediately threw them into the fireplace, where they burned quickly.

He also said that he had been writing something about Sendak and visited him. Sendak showed him 70 volumes of journals he had kept for most of his life. Kushner said he would like to read them. “Oh, no” Sendak said. “Nobody else will ever read these.” They were gone when he died.

As the event broke up and Kushner rose to leave, he turned to me. “Thank you so much, Leslie,” he said, and hugged me.

After the evening talk, which was mostly about Abraham Lincoln and Kushner’s recent screenplay, my friend Judy Kerman suggested that it was time for us to watch “Angels in America” again. She’s right. But first I have to get to “Lincoln.”

Photo by Judith Kerman, at Inquiring Minds, Saugerties

Photo by Judith Kerman, at Inquiring Minds, Saugerties

The Woodstock-Mayapple Poets’ Retreat took place during the first week of August. I was invited to participate. It turned out to be a life-transforming experience, one I’ll never forget.

When I went to college I earned an honors major in Creative Writing, and when I started my studies I was hoping to make my living writing fiction. By the time I got my degree, though, I had taken a major detour in my life, marrying a woman with three children and leaving school to earn a living for my new family. I finished school at night while working, but the degree seemed irrelevant by then and I’ve never used it. Twenty years ago I wrote a novel, just to see if I could do it. When I was finished I was proud of myself for completing the task, but the typescript is still sitting in my filing cabinet. I’ve written professionally through my adult life, but most of that has been music criticism and articles. My greatest creative writing “sale” was $5 for a short story I wrote in college.

In a previous article I wrote how a series of bad dreams in 1999 propelled me towards poetry, which I had never written seriously before. Starting a new means of expression in my mid-50s was exciting, but it also left me feeling seriously “behind” and in need of help. I’ve gotten some wonderful assistance with my work. My wife, and a poet named J.J. Clarke, both provided me with much advice and criticism in my early days. My first formal poetry instruction represented “starting at the top,” two workshops at Omega Institute with Sharon Olds. She is a wonderful teacher as well as a great poet, and I wish I could have continued studying with her. But after the second workshop, in 2009, she discontinued her summer workshops at Omega. When I ran into her at the Dodge Poetry Festival in 2010, she told me she had decided to reduce her teaching as much as possible, to concentrate on her own work. Even I couldn’t argue with that.

Last summer Omega offered a “Celebration of Poetry,” led by Marie Howe, with guests Patricia Smith, Mark Doty, and Billy Collins. It turned out to be very stimulating, but it was very different from Olds’s workshops, which were limited to ten selected participants. There were 91 attendees at the “Celebration of Poetry.” And for some reason Omega didn’t repeat the program this summer.

For several years, I have been meeting monthly with a group of fellow poets from my own area. We call ourselves the Goat Hill Poets, from the address of my former home where we started meeting. I’ve gotten tremendous help from my fellow Goats, who have done a lot to help me sharpen my game. (We’ve also become an occasional performing group, having great fun with our readings. The next one is in Woodstock on August 22.) Recently I started a second monthly meeting with two other poets, Jay Wenk and Judith Kerman, where I’ve been getting even more help.

Judy moved to Woodstock relatively recently. She is not only a widely published poet but also a publisher, running the Mayapple Press, with over 100 titles. A decade ago, when she was still teaching in Michigan, Judy started what she called the “Rustbelt Roethke” poets’ retreat (because it met in Roethke’s home town, Saginaw). Rather than meeting with someone of elevated status, a teacher, Judy’s retreat gathered equals, all successful, published poets, who met in small groups to workshop their poems. After moving to Woodstock, Judy decided to bring the workshop with her and re-titled it to include the magic name Woodstock.

When Judy first suggested that I attend this summer’s retreat, I was very hesitant. Although I know I’ve made a lot of progress since I started writing poetry, I wasn’t at all sure I would fit in with a group of professionals like these. “Oh, don’t worry,” she told me. “You’ll hold your own.” I was a little skeptical, but I decided to give it a try.

The retreat began on Tuesday evening with a picnic meal at the site, the Villetta Inn, a large summer “hotel” which was built as part of the famous Byrdcliffe Colony in Woodstock. We then had two hour sessions for the next four mornings with two or three other poets who would be our working group. Wednesday, Thursday, and Saturday, we also had readings of our work in various locales. I was scheduled for Saturday afternoon at a bookstore in Saugerties.

My two working partners were both people who intimidated me at first, Geraldine Connolly and Robert McDonough. Both are college professors and long-time poets with numerous prestigious publications to their credit. Both brought poems to work on which impressed me a great deal. I had brought problems, poems that seemed to me failures but which had enough I cared about in them so that I wanted to rescue them. Very quickly I discovered that Judy had been right. Listening in the focused way that develops in a workshop situation, I was able to come up with useful suggestions for both Gerry and Bob. They took my work seriously and gave me some excellent help.

In one case, for example, a sort of travelogue poem I’d written about a visit to Killarney, they helped me amputate about half of what I’d written by noticing–as I hadn’t–that the essential matter of the poem is about my experiences of music there. Some other aspects of the visit brought up in the poem might have been interesting, but they detracted from its focus. I was left with something that worked.

At the readings, too, I felt my work was appropriate and that I fit in. I got very good comments from others after my little feature in Saugerties. Best of all, I’ve heard from a couple of the people in the retreat, and I’m hoping to continue and maintain some new friendships. I had met only two of the others, Judy and one other commuter, before.

Perhaps the most inspiring person I met at the Woodstock-Mayapple Poets’ Retreat was a Chinese-American man named Li C. Tien. Li moved to America about 15 years ago, when he was already in his fifties. Since then he has mastered the use of written English so well that he has been writing poems in English for ten years and has had numerous poems published in fine magazines. I may think of myself has having gotten a late start, but Li will be an ongoing inspiration to me.

I’ll never be able to thank Judy and the other poets for the experience I shared with them. During this week I have come to take my own writing more seriously and I’ve become more ambitious. The Goat Hill group had decided collectively to push each other towards submitting more work, and I’ve already had a very nice acceptance from a magazine called Blue Unicorn (which has also published Li C. Tien). But I’ll definitely be doing more of that in coming weeks and months. And I am writing this blogpost, intended as a tribute and a gesture of thanks towards my fellow poets.

Right Words

With fragrance of honeysuckle in the air,

water pumped over one hand,

a word spelled into the other

by her teacher, suddenly

Helen Keller connected

what she felt with its name,

and wanted to know

the word for the next thing she touched.

Then, the next and the next.

Her sullen face lit up.

Struggling to connect my words

with the world, the universe,

I remember the scene at the well.

–Li C. Tien

Blue Unicorn, 2012

One summer I attended a huge party in rural Indiana hosted by science-fiction fans and writers Buck and Juanita Coulson. When the party was down to about 20 people, Buck pulled out a book of poems and offered a prize to anyone who could read through one of them without cracking up. Nobody made it.

This event, when I was a teenager, was my introduction to great bad art. The poet, who is still unknown even to most connoisseurs of inadvertent humor, was Violette Peaches Watkins. The book, her second, was “My Dream World of Poetry: Poems of Imagination, Reality and Dreams.” Mrs. Watkins was “a popular radio announcer on Station WHFC, Chicago, and a prominent patron of the arts,” according to the dust jacket. (I’ve guessed this means she was a gospel music DJ, since many of her poems have a religious theme, but I have no evidence.) My friend Marianna Boncek has done some research on Mrs. Watkins and discovered that she was apparently well known in black artistic circles in Chicago.

I searched for a copy of “My Dream World” for four decades, even though I had a photocopy provided to me, years after the party, by Buck. I used to tell people I was confident I would die without ever finding a copy, but I was wrong. Eventually an Internet search turned up two copies from the same seller, and I bought them both. Hey, you never know.

Incidentally, when I first told Marianna about the book and the contest, she told me with great confidence that she was certain she could read one of the poems without problems, having read plenty of awful poems produced by the students she teaches. She got through three lines of Mrs. Watkins and started laughing so hard she couldn’t go any further.

Mrs. Watkins has the qualities required by artistic inadvertent humor: ambition, incompetence, and gradiosity. They’re all necessary, and when done “right” they add up to a kind of anti-genius. I have seen plenty of movies made more ineptly than those of Ed Wood. Mill Creek Video has issued three 50-film collections of amateur horror movies, “Catacomb of Creepshows,” “Tomb of Terrors,” and “Decrepit Crypt of Nightmares.” The ones I’ve watched are incredibly awful but few of them are funny.

Mrs. Watkins’s “best” poems go on for several pages. But I want to quote one complete, so here is one that shows off her typical qualities:

The Cure for Juvenile Delinquency

You must start, from the beginning of time,

Praying hard daily, at least three times,

Thanking Almighty God for what you’ve got,

To be sure He will take care of that.

If your prayers successfully reach God’s throne,

Your child will be trained before it’s born;

For the Almighty God, who made heaven and the universe,

Will guide your child while it’s on this good earth.

Both parents should be faithful, loyal and true,

Because your child will have characteristics of you;

This much you owe to your child before it’s born:

To be brilliant, healthy and have a happy home.

Pray that he will be a blessing to humanity

And won’t lead a life of crime and insanity;

Pray hard that he will walk in God’s light;

Pray that he will always live upright.

And somewhere, sometime, the day will come

You’ll be repaid for the songs you’ve sung,

The prayers you’ve prayed, your toil and patience,

For being faithful and true, and your kind consideration.

There’s no reason to point out all the many reasons why I consider Mrs. Watkins the greatest bad poet I’ve ever read–even funnier than the legendary William McGonagall. All I can say is that if anyone ever finds a copy of her first book, “Violette Peaches’ Book of Modern Poetry for All Occasions,” let me know. I’m offering serious money!

I can think of only two other producers of legendary bad art whose work makes me laugh a lot. One is the singer Florence Foster Jenkins, who in her brief career managed to convulse thousands of music lovers, without ever realizing that people were laughing at her. Jenkins’s rich husband wouldn’t allow her to perform in public. After his death, though, she started a series of salons which eventually grew to concerts in hotel ballrooms and finally, in her last great moment of triumph, a sold-out recital at Carnegie Hall. No doubt such recitals would have become annual events had she not died soon afterwards.

Listening to Mrs. Jenkins carefully–which is, I admit, difficult–you can actually hear some suggestions of musicianship. And she doesn’t sing consistently out of tune. (If she had, she would have been less funny.) But hearing her grasp for the notes in the famous aria of the Queen of the Night from Mozart’s “Magic Flute” is an experience which continues to crack me up even after having heard it for more than 50 years. It’s also fun to hear her accompanist, one Cosme McMoon (his real name!), trying to keep up with her. We are fortunate indeed that Mrs. Jenkins decided to immortalize her art on private recordings, which she sold only directly to individual music lovers after interviewing them and making sure they were sufficiently educated in music to appreciate her work.

Mrs. Jenkins’s recordings are most conveniently available in a reissue from the Naxos label. My friend Gregor Benko’s collection “The Muse Surmounted” includes an interview with McMoon as part of a collection of other bad singers whose work he has enjoyed. One of them is Vassilka Petrova, whom operaphiles generally consider the worst singer to record a complete opera role. (She did two for the early bargain-priced Remington label. Rumor has it that she was married for a time to Remington’s owner.) When I was a dealer in classical LP records, I always rejoiced when I found a Petrova recording. They sold for very high prices. Follow the link above and you will be able to buy all of Petrova’s LP recordings on CD!

Then, of course, there’s the great bad film director Edward D. Wood, Jr. His “Plan 9 from Outer Space” is often cited as the worst film ever made, but it’s definitely not. His first feature, “Glen or Glenda,” is even worse (and perhaps even funnier), and the 1930s films of Dwayne Esper (probably best known for “Maniac”) are certainly worse in all respects. But it’s the grandiose stupidity of Wood’s dialogue that makes his films among the greatest examples of inadvertent humor ever produced. You can demonstrate this by seeing movies like “Orgy of the Dead” or “The Violent Years,” which are hilarious even though Wood only wrote the scripts and did not direct them.

Since most of Wood’s work is now in the public domain, it’s relatively easy to find. Two useful collections of Wood’s worst have now gone out of print, and the new “Big Box of Wood,” as wonderful as it is, doesn’t have “Glen or Glenda” in it. If you’re curious try “Plan 9” or this collection.

What do we gain by laughing at the ineptitude of others? Well, the most useful element I can think of is the way bad art illuminates the difficulties of creating great art. Seeing how badly Wood’s films demonstrate elements of film making we usually take for granted, I realize just how hard it is to make even a competent run-of-the-mill film. But the hell with that. Mostly what we gain are laughs, which are always useful. I still remember the experience of my old friend Sasha Gillman, who unwillingly accompanied her husband Jerry to my house for an Ed Wood Night. (I still do these!) She said she wouldn’t find anything to laugh about in a bad movie, and she wound up laughing so hard she literally fell off the couch.

As recently as fifteen years ago, the idea that I could become seriously involved with poetry would have been very remote to me. I’d been a minor poetry consumer all my life, but I’d never become very interested in writing it, until a series of nightmares changed everything.

When I was quite young, I wrote some verse. I remember that a narrative verse I wrote about the second century Jewish hero Bar Kokhba won a writing prize for students offered by my synagogue, Temple Beth Emeth in Brooklyn, and was printed in the synagogue newsletter. I would have been about twelve then. I was definitely eleven when the Brooklyn Dodgers won their only World Series, beating the hated Yankees in 1955. I wrote a verse about that event, and I even remember a few lines of it:

Traffic jams. Loud horns all night.

Policemen smiled, saying, “It’s all right.

It’s just Brooklyn celebrating

after fifty years of waiting.”

Not too bad for a little kid, but not exactly an indicator of great talent!

In junior high school, I won an elocution contest for reciting an old piece of comic verse, “The Owl-Critic” by James Thomas Fields. My prize was an anthology of English language poetry, which I still have. But I didn’t read most of it. In high school I took a poetry class, mostly because the teacher, Harold Zlotnik, was a friend of my father’s. Harold, whom I’ve reconnected with in recent years, is now in his late 90s. I was impressed that his poetry was frequently published in the New York Times, which used to run poems on its editorial page. In Harold’s class I read Theodore Roethke’s “Elegy for Jane,” which began a lifelong love for that particular poet. He took his class to the 92nd Street Y to hear readings by Carl Sandburg and Robert Frost. So I was at least exposed to good stuff.

During my junior high and high school years I was intensely involved with science fiction fandom, although I never wrote any science fiction myself. I ran into a phenomenon called “filk songs,” folk songs rewritten with humorous lyrics. I wrote a few of those which were moderately successful, getting some practice in creating rhymed lines for an audience.

At Brooklyn College I studied poetry in literature classes. I earned an honors degree in Creative Writing (which I never used for any purpose), but my interest then was in writing fiction. I wrote a parody of T.S. Eliot’s “The Hollow Men” (which I didn’t like) called “The Fallow Men,” and as I recall it had a few clever lines in it. (I also wrote a parody of Kafka’s “The Trial,” which I admired tremendously.)

My interest in poetry remained relatively mild. My first date with my first wife was a memorial to Theodore Roethke, but I think I was mostly trying to impress her. In the late Sixties I had some correspondence with Roethke’s widow Beatrice Lushington about publishing a reading of his on my Parnassus LP label. Just before we were ready to go to print, she finally heard from Caedmon that they were interested in the recording, so I told her to go with them since they would sell a lot more copies.

From time to time through my adult life, some poetry or other would catch my attention. I wasn’t closed to it. But it wasn’t a major pursuit of mine.

The disastrous close of a brief toxic romance in 1983 got me started writing songs. I was still playing the piano in those days and I started performing them, along with favorites by other songwriters like Randy Newman, Warren Zevon, and Little Richard. I wrote a lot of song lyrics over a period of a few years, more than a hundred of them. But song lyrics aren’t poems.

In 1997, I moved from my long term rental of “Big Pink” in Saugerties to another house nearby which I was able to buy. Not long after I moved into the new house, I started having terrible nightmares about death. They happened only in that house, not when I stayed at Tara’s, and usually during midday naps rather than at night. But they were really frightening. Eventually, I hired a psychic I knew slightly. She told me I was being haunted by the spirit of a child who had been killed on my property, probably several hundred years earlier, and she did something to set the child’s spirit free. I didn’t believe in any of this, but the little ceremony she performed set something free in my psyche and the nightmares stopped.

During the nightmare period, though, I started writing poems. They were all about death and dying. As I read them now, they don’t seem particularly bad work for a novice poet, although I wouldn’t want most of them exposed. My favorite was one I wrote after a walk through an ancient cemetery near my parents’ house on Cape Cod. I saw several tombstones that were no longer legible at all, and I sat down on a bench and wrote:

I have been dead so long

even the stone cannot remember my name.

You think I wait beneath the earth

to feel your footfall,

but it is not so. I fly above my grave

where I can smell the salt and hear the waves

and watch you, looking down,

fearing when you will join me.

Shortly before the nightmare period, I had become interested in another poet, J.J. Clarke. The Woodstock Times, for which I wrote music reviews (and still do), used to run work by local poets, and Clarke’s poems knocked me out. He used to read once a year at the old Woodstock Poetry Society, back in its glory days when Bob Wright was running it. I went to hear him, which proved a great but intimidating experience. The poems were wonderful, and his reading was the most powerful I’d ever heard.

After the reading I bought a chapbook, and had James inscribe it for me. He recognized my name immediately, and it turned out that he had been a regular listener to my radio program in the 1980s. He asked me if I wrote poems, and I told him I had just started but they weren’t much good. He invited me to send me some. Apparently, he saw more talent in them than I did, because he sent them back with comments and suggestions and invited me to send more.

This was the beginning of a mentoring relationship which went on for several years. James was an experienced teacher–he taught poetry at Ulster County Community College for 25 years–and his comments were extremely useful. I also got a lot of useful feedback from my wife Tara, who had read much more poetry than I had and had already written some wonderful poems herself, most of which she never showed to anyone.

So, I kept writing. I found a lot of stimulation in the monthly meetings of the Woodstock Poetry Society, and started reading some of my own work in the open mike sections. After a few years, Bob Wright invited me to be one of his featured readers, my first time as a feature. The Woodstock Poetry Festival, a marvelous although quixotic enterprise, brought a number of major poets to Woodstock for a couple of years. Hearing people who had been only names on a page, like Sharon Olds and Billy Collins, turned out to be inspiring.

One of our best Ulster County poets, Cheryl A. Rice, invited me to a poetry salon she had decided to host. We had only two meetings, but I found those sessions tremendously useful, not only for the feedback I got on my work but also for the way it focused my attention on what was happening in other poets’ work. When Cheryl told me she hadn’t continued the salons because she didn’t want to be stuck cleaning her house on schedule, I invited her to start the meetings up again at my house, since I had a paid house cleaner. Because my house was on Goat Hill Road, we became the Goat Hill Poets, and we still are even though we now meet at Tara’s house in Woodstock.

I was intrigued when I learned that Sharon Olds, one of the poets I most admire, was teaching workshops at Omega Institute in nearby Rhinebeck. Attendance at these workshops was by invitation only, and the first two times I submitted work I wasn’t invited. The third time, though, in 2007, I was invited as an alternate, and someone dropped out. I got to work for a long weekend with Sharon Olds in a small group, ten of us. I thought everyone else wrote better than I did. But for the final session, I wrote a snidely satiric poem about Omega itself. Seeing the whole group, including Sharon, laughing heartily at my work gave me a sense of poet power that I’d never had before.

The following summer I got to work with Sharon and nine others for a full week. It was an incomparably nourishing experience. At the next to last session, she challenged us to write something that was difficult to write. I wrote a poem about my wife Tara and our experiences together, and “My Love” won a prize in the Prime Time Cape Cod poetry contest. It was just honorable mention, but it was $50 cash and a $25 gift certificate to Borders, a lot more than most poets receive for published work.

Unfortunately for me, Sharon has decided to limit her teaching and concentrate more on her own work, so she doesn’t teach at Omega anymore. Last summer, Omega had a very different type of event, a “Celebration of Poetry” hosted by the wonderful Marie Howe, with half-day visits from Mark Doty, Patricia Smith, and Billy Collins. With 91 people in attendance, I wasn’t expecting much. But I was surprised by the excellent experience it turned out to be. Collins, answering a question, said that he could recognize a talented poet by a gift for rhythm and a gift for metaphor. I’ve been surprised over the years to discover that I have both of those.

I’ve been a slacker about submitting my poetry for publication. But I have had a couple of poems published in Home Planet News, a long running poetry paper edited by Donald Lev. My father got to see the first one shortly before he died. I’ve had a few poems published elsewhere, including the Goat Hill Poets anthology issued in 2010 and in an article on the Goat Hill Poets published by Ulster Magazine. Aside from reading with the Goats, I’ve done various features in and around Woodstock, most recently July 4, 2011 at Harmony. (The link leads you to an audio recording.) On February 3, I was one of the featured poets at the excellent Calling All Poets Series in Beacon. A recording of that reading will shortly be available on the series website.

I’m still writing poetry. Unlike some of the really good poets I know, I don’t set aside regular time for writing. The ideas have to force themselves into my awareness for me to pay attention to them. But I’ve learned always to have a pad and pen with me.

(Top photo: Leslie reading in Kingston. Photo by Dan Wilcox.)

The great Polish poet Wisława Szymborska died last week at the age of 88. You can learn a great deal about my own taste in poetry, and ambitions for my own work, when I mention that she was one of my favorite poets ever.

Since Szymborska dealt so profoundly with the life of ordinary things, I’ll start off by telling you how to say her name correctly. That funny symbol of the L with the line through it, which I believe may be unique to the Polish language, is pronounced like a W in English. The W in Polish, as in some other languages, is our V. So her name is pronounced vis-WA-va shim-BOR-ska.

I am not really equipped to write an analysis or appreciation of Szymborska’s poetry. That task has already been accomplished satisfactorily by Billy Collins, in his introduction to “Monologue of a Dog,” the first collection of her work published in English after she was awarded the 1996 Nobel Prize for Literature. (Her friends referred to that event as the “Nobel Tragedy” because she stopped writing for several years after the prize was awarded.) Here’s the quote that appears on the dust jacket: Szymborska knows when to be clear and when to be mysterious. She knows which cards to turn over and which ones to leave facedown. Her simple, relaxed language dares to let us know exactly what she is thinking, and because her imagination is so lively and far-reaching–acrobatic, really–we are led, almost unaware, into the intriguing and untranslatable realms that lie just beyond the boundaries of speech.”

Collins is a profound fellow, despite the conversational nature of his prose and poetry, and he has given a good definition of poetry here, at least poetry as I conceive of it: “realms that lie just beyond the boundaries of speech.” That’s why I cannot summarize one of Szymborska’s poems–not only because they are so concise, but because in their selection of images, their unconventional thoughts, and their precise expression, they are indeed beyond the boundaries of speech. That paradox–using words to express what lies beyond words–is the nature of great poetry. Szymborska travels in that land very often, and in moving and surprising ways. And although I read her only in translation, I feel that I do understand what she is getting at. The concepts come across.

Although half of “Monologue of a Dog” is wasted on us because it includes the Polish originals of the poems as well as translations, I still recommend it as an introduction to her work. If you want to see how this modest woman, working in obscurity as an editor at a Polish literary magazine, developed her unique voice, you can get either of the earlier English language collections, “Poems New and Collected” or “View with a Grain of Sand.” Both volumes include a lot more poems than “Monologue of a Dog,” and both include many examples of the work Szymborska did–including much rhyming verse–on her way to mastery. But “Monologue of a Dog” is all masterpieces. It includes the great title poem, which shows how the choice of a limited perspective (a dog’s) on human activity illuminates human experience; “A Few Words on the Soul,” as amusing as it is a profound exploration of human nature; and the heartrending “Photograph from September 11,” in which a few words recreate the awful experience of that day with the most beautiful compassion and sorrow. These poems are magic tricks as much as they are explorations of the experiences we share.

If you don’t know this magnificent poet, even if you are usually not a poetry consumer, take a few minutes to read some of her work. These poems may not change your life the way they have mine, but the will put you in touch with one of the most beautiful people ever to walk our planet.

You can find out more about Wislawa Szymborska on the Culture.pl page about her at http://www.culture.pl/web/english/resources-literature-full-page/-/eo_event_asset_publisher/eAN5/content/wislawa-szymborska

Writing the informal essays that I contribute to this site takes me back to my teens, when I was very much involved in science fiction fandom. The kind of writing I do here evolved from the fanzines I wrote for and sometimes published, and from writing I read at that time.

These days the term “blog” covers a much wider range of formality than I was used to in the past. There are now thoroughly professional “blogs” on line. I still think of the blog as a loose, informal style descended from the great essayists of the past, like the French Renaissance writer Montaigne–who popularized the genre–and the English writers Joseph Addison and Richard Steele, whose “The Spectator” (1711-12) was the Huffington Report of its day.

There were two highly diverse writers of my teens whose inspiration I still feel, both named Harry. One of them was widely known to the public: Harry Golden. The other was known only to science fiction fandom and the inhabitants of his home town: Harry Warner, Jr., the Hermit of Hagerstown.

I subscribed for several years to Golden’s weekly “newspaper” The Carolina Israelite. He wrote and published it from 1942 to 1968. I read it in the 1950s, and of course read his collections of columns, starting with the best-selling “Only in America.” I remember Golden, whom I haven’t read in a long time, as a superb informal essayist. He wrote reminiscences of his own life, including (after it was exposed) a frank discussion of time he had spent in prison for fraud following the 1929 crash. He became famous for “The Vertical Negro Plan,” a marvelous satiric essay in which he observed that racial integration was a problem only in places where people sat down. His solution to the problem was to remove seats in places where integration was a contested issue, like lunch counters and schools.

The content of Golden’s writing was interesting and sometimes challenging. But what made him so popular was his amusing means of expression. You could read a Golden essay on virtually any topic and remain engaged because he made you smile. “Only in America” was his fourth book, but it was the first one collected from the Israelite. Readers quickly discovered how entertaining Golden’s writing was and the book became a huge best-seller. He also came across well in frequent radio and television appearances.

Harry Warner, Jr. was a very different sort of person and writer from Golden. He was a newspaper reporter in his home town of Hagerstown, Maryland, who became interested in science fiction and science-fiction fandom in their early days. He published his first fanzine in 1938, and continued active in fan writing until he died in 2003. He also wrote some science fiction and a book-length history of fandom, “All Our Yesterdays.”

Harry was a voluminous correspondent, sending a letter of comment to any fanzine he received and answering all letters. I began writing to him occasionally when I was in my mid teens. We had some things in common that we both appreciated. We were both greatly interested in classical music. I was a poor piano student. Harry was an accomplished pianist and oboist who performed locally. We both wrote music reviews.

For decades, Harry was a mainstay of the Fantasy Amateur Press Association (FAPA), a group which circulated fanzines published by its members to those members. Some of these fanzines went only to FAPA members; others had some outside circulation. Harry sent copies of his Horizons to me for several years. His training and discipline were awesome. He would start out with a quire of mimeograph stencils (24), compose his writing directly onto the stencils, and finish his last essay on the last line of page 24. As I recall the essays were bloglike, informally written and not the products of great research or contemplation, yet they were always interesting to read.

Harry got his nickname, “the Hermit of Hagerstown,” from his reluctance to travel or to engage in much personal contact with others outside his work. I was one of the few science fiction fans who got to meet him on his home turf. In 1960 I went to Franklin and Marshall College in Lancaster, Pennsylvania, within a few hours of Hagerstown. I was there for only six months, but during my fall semester I maintained my correspondence with Harry and he invited me to visit him. I got a ride with a classmate to Hagerstown, returning to Lancaster by bus. Harry was very welcoming and genial, taking me to eat in his favorite places. We spent the evening listening to some favorite classical recordings. It was a real treat.

I dropped out of science fiction fandom in my late teens and lost touch with Harry. I was a little surprised to learn that he had remained active until the end of his life. Now I regret that I didn’t write to him years ago and share with him details of my activities as a classical music critic, record dealer, and publisher. I’m sure he would have been pleased.

I still remember the writing of these two Harries, and I remain happily influenced by both of them.

About a year ago, I was surprised to get a hit from eBay on my Leslie Gerber search. Someone offered an APAzine that I had written and published. (It wasn’t from FAPA, which I never did get into; it had a very long waiting list.) The first page was posted in the offering, and I got to read it. I wrote about the some of same things that interest me today, including classical music and literature, as well as personal comments answering things other people in the group had written about. I was fascinated to encounter my teenage self in this way and would have liked to read the whole thing. But somebody outbid me.

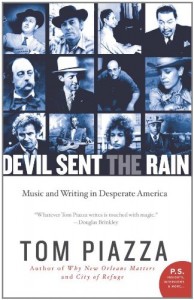

When I write to recommend a new book by Tom Piazza (“Devil Sent the Rain: Music and Writing in Desperate America”), I have to say immediately that Tom is a friend of mine, although we have met in person only half a dozen times. Starting with a phone call he made to me a decade ago from Cape Cod, seeking recommendations for Sviatoslav Richter recordings, we have maintained a lively and wide-ranging contact through e-mails and phone conversations. In recent years our contact has diminished, mostly because Tom’s increasing success as a writer has left him with what one writer described as “a choice between writing novels and writing e-mails.” Still he is a best buddy and I have to admit that I hope you will be interested in his book because I want it to be a success.

Reading through the essays in “Devil Sent the Rain: Music and Writing in Desperate America”, you will get a pretty good idea of the range of Tom’s interest, although it’s definitely not a complete survey. (Among other omissions, there’s nothing here about Gustav Mahler’s music or Sviatoslav Richter’s piano playing.) Although he studied writing at Williams College, he was also a serious pianist and for a time supported himself playing jazz piano. His “The Guide to Classic Recorded Jazz”

although now outdated as a guide to current issues, is the best critical guide to jazz recordings I’ve ever read. (My late friend Marty Laforse, a historian whose jazz background went back as far as hearing Fats Waller play, borrowed a copy of the Guide from me and refused to return it; I had to buy another copy.) He has written a book of short stories and two novels in addition to various nonfiction, and there is another novel currently in the works.

Tom moved to New Orleans fifteen years ago, after being attracted for years by the city’s music and general culture. He was en route home when the disaster we conveniently call Hurricane Katrina (although it was not the hurricane itself which caused most of the disaster) struck the city. Holed up in temporary quarters at his girlfriend’s parents’ home in Missouri, in response to a request from his publisher, he wrote the remarkable short book “Why New Orleans Matters” in five weeks. (Get the paperback edition, which has supplementary chapters.) This essay fulfills its title, and it’s indispensable for people seeking to understand the uniqueness of the city’s nature and its necessary place in America. He followed this up with the equally remarkable novel “City of Refuge,”

a portrait of New Orleans after Katrina as seen through two very different families’ experiences. I still don’t understand why this book failed to become a best-seller and a blockbuster movie.

“Devil Sent the Rain” is a collection of separate essays written for a wide variety of purposes and not originally intended to be published together. Issuing a book like this seem to indicate that Tom’s publisher believes he has a fan base large enough to justify a miscellaneous collection, which is gratifying to know. He has tied the material together with little introductions, much in the manner of Norman Mailer’s “Advertisements for Myself”. Since Tom was a close friend of Mailer’s for years, and includes two pieces about Mailer, it’s an obvious influence.

The subtitle of the book is accurate. The first section is devoted to essays on a wide variety of musicians, including Jimmy Martin (a lengthy piece once issued as a separate book), Jelly Roll Morton, Bob Dylan (a longtime interest of Piazza’s), Jimmie Rodgers, Carl Perkins (how I envy him that meeting!), Charley Patton, and others, including the Grammy-winning program notes to the Martin Scorsese “Blues” collection. Even when reading about musicians I was already well familiar with, like Perkins and Morton, I found new insights and illuminations in these essays. Others sent me back to my CD collection to rehear (and supplement) my understanding of the subjects. In fact, reading this book has already cost me a couple of hundred dollars in CD purchases, so beware.

The second section is about the writing and the desperation. I’m not sure how Charlie Chan wound up here (and, frankly, after watching a couple of the movies, I am still unconvinced by Tom’s arguments in favor of them). The writing material includes Mailer, general comments on literature, Flaubert, and a wonderful “self-interview” which shows Tom’s wicked sense of humor better than any other published writing of his I’ve seen. The desperation relates mostly to New Orleans, and includes some articles and on-line exchanges from shortly after Katrina which add further understanding of the situation beyond what’s in “Why New Orleans Matters”

The last essay is one which may appeal mostly to collectors, particularly record collectors like myself. It’s about a surprisingly successful expedition which led to acquiring some very rare 78s. I suspect there’s some illuminating material about the nature of collecting in here also, but frankly, I can’t be sure, being afflicted with that syndrome myself.

“Devil Sent the Rain” isn’t the most essential Piazza for newcomers to his writing. For the best introduction, go to “Why New Orleans Matters”

and “City of Refuge.”

But it’s a very entertaining collection, showing vividly the expressive and concentrated nature of his writing even while remaining spontaneous. I guess those qualities are just in his nature by now. They’re everywhere in “Why New Orleans Matters” despite the haste in which it was written.