One summer I attended a huge party in rural Indiana hosted by science-fiction fans and writers Buck and Juanita Coulson. When the party was down to about 20 people, Buck pulled out a book of poems and offered a prize to anyone who could read through one of them without cracking up. Nobody made it.

This event, when I was a teenager, was my introduction to great bad art. The poet, who is still unknown even to most connoisseurs of inadvertent humor, was Violette Peaches Watkins. The book, her second, was “My Dream World of Poetry: Poems of Imagination, Reality and Dreams.” Mrs. Watkins was “a popular radio announcer on Station WHFC, Chicago, and a prominent patron of the arts,” according to the dust jacket. (I’ve guessed this means she was a gospel music DJ, since many of her poems have a religious theme, but I have no evidence.) My friend Marianna Boncek has done some research on Mrs. Watkins and discovered that she was apparently well known in black artistic circles in Chicago.

I searched for a copy of “My Dream World” for four decades, even though I had a photocopy provided to me, years after the party, by Buck. I used to tell people I was confident I would die without ever finding a copy, but I was wrong. Eventually an Internet search turned up two copies from the same seller, and I bought them both. Hey, you never know.

Incidentally, when I first told Marianna about the book and the contest, she told me with great confidence that she was certain she could read one of the poems without problems, having read plenty of awful poems produced by the students she teaches. She got through three lines of Mrs. Watkins and started laughing so hard she couldn’t go any further.

Mrs. Watkins has the qualities required by artistic inadvertent humor: ambition, incompetence, and gradiosity. They’re all necessary, and when done “right” they add up to a kind of anti-genius. I have seen plenty of movies made more ineptly than those of Ed Wood. Mill Creek Video has issued three 50-film collections of amateur horror movies, “Catacomb of Creepshows,” “Tomb of Terrors,” and “Decrepit Crypt of Nightmares.” The ones I’ve watched are incredibly awful but few of them are funny.

Mrs. Watkins’s “best” poems go on for several pages. But I want to quote one complete, so here is one that shows off her typical qualities:

The Cure for Juvenile Delinquency

You must start, from the beginning of time,

Praying hard daily, at least three times,

Thanking Almighty God for what you’ve got,

To be sure He will take care of that.

If your prayers successfully reach God’s throne,

Your child will be trained before it’s born;

For the Almighty God, who made heaven and the universe,

Will guide your child while it’s on this good earth.

Both parents should be faithful, loyal and true,

Because your child will have characteristics of you;

This much you owe to your child before it’s born:

To be brilliant, healthy and have a happy home.

Pray that he will be a blessing to humanity

And won’t lead a life of crime and insanity;

Pray hard that he will walk in God’s light;

Pray that he will always live upright.

And somewhere, sometime, the day will come

You’ll be repaid for the songs you’ve sung,

The prayers you’ve prayed, your toil and patience,

For being faithful and true, and your kind consideration.

There’s no reason to point out all the many reasons why I consider Mrs. Watkins the greatest bad poet I’ve ever read–even funnier than the legendary William McGonagall. All I can say is that if anyone ever finds a copy of her first book, “Violette Peaches’ Book of Modern Poetry for All Occasions,” let me know. I’m offering serious money!

I can think of only two other producers of legendary bad art whose work makes me laugh a lot. One is the singer Florence Foster Jenkins, who in her brief career managed to convulse thousands of music lovers, without ever realizing that people were laughing at her. Jenkins’s rich husband wouldn’t allow her to perform in public. After his death, though, she started a series of salons which eventually grew to concerts in hotel ballrooms and finally, in her last great moment of triumph, a sold-out recital at Carnegie Hall. No doubt such recitals would have become annual events had she not died soon afterwards.

Listening to Mrs. Jenkins carefully–which is, I admit, difficult–you can actually hear some suggestions of musicianship. And she doesn’t sing consistently out of tune. (If she had, she would have been less funny.) But hearing her grasp for the notes in the famous aria of the Queen of the Night from Mozart’s “Magic Flute” is an experience which continues to crack me up even after having heard it for more than 50 years. It’s also fun to hear her accompanist, one Cosme McMoon (his real name!), trying to keep up with her. We are fortunate indeed that Mrs. Jenkins decided to immortalize her art on private recordings, which she sold only directly to individual music lovers after interviewing them and making sure they were sufficiently educated in music to appreciate her work.

Mrs. Jenkins’s recordings are most conveniently available in a reissue from the Naxos label. My friend Gregor Benko’s collection “The Muse Surmounted” includes an interview with McMoon as part of a collection of other bad singers whose work he has enjoyed. One of them is Vassilka Petrova, whom operaphiles generally consider the worst singer to record a complete opera role. (She did two for the early bargain-priced Remington label. Rumor has it that she was married for a time to Remington’s owner.) When I was a dealer in classical LP records, I always rejoiced when I found a Petrova recording. They sold for very high prices. Follow the link above and you will be able to buy all of Petrova’s LP recordings on CD!

Then, of course, there’s the great bad film director Edward D. Wood, Jr. His “Plan 9 from Outer Space” is often cited as the worst film ever made, but it’s definitely not. His first feature, “Glen or Glenda,” is even worse (and perhaps even funnier), and the 1930s films of Dwayne Esper (probably best known for “Maniac”) are certainly worse in all respects. But it’s the grandiose stupidity of Wood’s dialogue that makes his films among the greatest examples of inadvertent humor ever produced. You can demonstrate this by seeing movies like “Orgy of the Dead” or “The Violent Years,” which are hilarious even though Wood only wrote the scripts and did not direct them.

Since most of Wood’s work is now in the public domain, it’s relatively easy to find. Two useful collections of Wood’s worst have now gone out of print, and the new “Big Box of Wood,” as wonderful as it is, doesn’t have “Glen or Glenda” in it. If you’re curious try “Plan 9” or this collection.

What do we gain by laughing at the ineptitude of others? Well, the most useful element I can think of is the way bad art illuminates the difficulties of creating great art. Seeing how badly Wood’s films demonstrate elements of film making we usually take for granted, I realize just how hard it is to make even a competent run-of-the-mill film. But the hell with that. Mostly what we gain are laughs, which are always useful. I still remember the experience of my old friend Sasha Gillman, who unwillingly accompanied her husband Jerry to my house for an Ed Wood Night. (I still do these!) She said she wouldn’t find anything to laugh about in a bad movie, and she wound up laughing so hard she literally fell off the couch.

As recently as fifteen years ago, the idea that I could become seriously involved with poetry would have been very remote to me. I’d been a minor poetry consumer all my life, but I’d never become very interested in writing it, until a series of nightmares changed everything.

When I was quite young, I wrote some verse. I remember that a narrative verse I wrote about the second century Jewish hero Bar Kokhba won a writing prize for students offered by my synagogue, Temple Beth Emeth in Brooklyn, and was printed in the synagogue newsletter. I would have been about twelve then. I was definitely eleven when the Brooklyn Dodgers won their only World Series, beating the hated Yankees in 1955. I wrote a verse about that event, and I even remember a few lines of it:

Traffic jams. Loud horns all night.

Policemen smiled, saying, “It’s all right.

It’s just Brooklyn celebrating

after fifty years of waiting.”

Not too bad for a little kid, but not exactly an indicator of great talent!

In junior high school, I won an elocution contest for reciting an old piece of comic verse, “The Owl-Critic” by James Thomas Fields. My prize was an anthology of English language poetry, which I still have. But I didn’t read most of it. In high school I took a poetry class, mostly because the teacher, Harold Zlotnik, was a friend of my father’s. Harold, whom I’ve reconnected with in recent years, is now in his late 90s. I was impressed that his poetry was frequently published in the New York Times, which used to run poems on its editorial page. In Harold’s class I read Theodore Roethke’s “Elegy for Jane,” which began a lifelong love for that particular poet. He took his class to the 92nd Street Y to hear readings by Carl Sandburg and Robert Frost. So I was at least exposed to good stuff.

During my junior high and high school years I was intensely involved with science fiction fandom, although I never wrote any science fiction myself. I ran into a phenomenon called “filk songs,” folk songs rewritten with humorous lyrics. I wrote a few of those which were moderately successful, getting some practice in creating rhymed lines for an audience.

At Brooklyn College I studied poetry in literature classes. I earned an honors degree in Creative Writing (which I never used for any purpose), but my interest then was in writing fiction. I wrote a parody of T.S. Eliot’s “The Hollow Men” (which I didn’t like) called “The Fallow Men,” and as I recall it had a few clever lines in it. (I also wrote a parody of Kafka’s “The Trial,” which I admired tremendously.)

My interest in poetry remained relatively mild. My first date with my first wife was a memorial to Theodore Roethke, but I think I was mostly trying to impress her. In the late Sixties I had some correspondence with Roethke’s widow Beatrice Lushington about publishing a reading of his on my Parnassus LP label. Just before we were ready to go to print, she finally heard from Caedmon that they were interested in the recording, so I told her to go with them since they would sell a lot more copies.

From time to time through my adult life, some poetry or other would catch my attention. I wasn’t closed to it. But it wasn’t a major pursuit of mine.

The disastrous close of a brief toxic romance in 1983 got me started writing songs. I was still playing the piano in those days and I started performing them, along with favorites by other songwriters like Randy Newman, Warren Zevon, and Little Richard. I wrote a lot of song lyrics over a period of a few years, more than a hundred of them. But song lyrics aren’t poems.

In 1997, I moved from my long term rental of “Big Pink” in Saugerties to another house nearby which I was able to buy. Not long after I moved into the new house, I started having terrible nightmares about death. They happened only in that house, not when I stayed at Tara’s, and usually during midday naps rather than at night. But they were really frightening. Eventually, I hired a psychic I knew slightly. She told me I was being haunted by the spirit of a child who had been killed on my property, probably several hundred years earlier, and she did something to set the child’s spirit free. I didn’t believe in any of this, but the little ceremony she performed set something free in my psyche and the nightmares stopped.

During the nightmare period, though, I started writing poems. They were all about death and dying. As I read them now, they don’t seem particularly bad work for a novice poet, although I wouldn’t want most of them exposed. My favorite was one I wrote after a walk through an ancient cemetery near my parents’ house on Cape Cod. I saw several tombstones that were no longer legible at all, and I sat down on a bench and wrote:

I have been dead so long

even the stone cannot remember my name.

You think I wait beneath the earth

to feel your footfall,

but it is not so. I fly above my grave

where I can smell the salt and hear the waves

and watch you, looking down,

fearing when you will join me.

Shortly before the nightmare period, I had become interested in another poet, J.J. Clarke. The Woodstock Times, for which I wrote music reviews (and still do), used to run work by local poets, and Clarke’s poems knocked me out. He used to read once a year at the old Woodstock Poetry Society, back in its glory days when Bob Wright was running it. I went to hear him, which proved a great but intimidating experience. The poems were wonderful, and his reading was the most powerful I’d ever heard.

After the reading I bought a chapbook, and had James inscribe it for me. He recognized my name immediately, and it turned out that he had been a regular listener to my radio program in the 1980s. He asked me if I wrote poems, and I told him I had just started but they weren’t much good. He invited me to send me some. Apparently, he saw more talent in them than I did, because he sent them back with comments and suggestions and invited me to send more.

This was the beginning of a mentoring relationship which went on for several years. James was an experienced teacher–he taught poetry at Ulster County Community College for 25 years–and his comments were extremely useful. I also got a lot of useful feedback from my wife Tara, who had read much more poetry than I had and had already written some wonderful poems herself, most of which she never showed to anyone.

So, I kept writing. I found a lot of stimulation in the monthly meetings of the Woodstock Poetry Society, and started reading some of my own work in the open mike sections. After a few years, Bob Wright invited me to be one of his featured readers, my first time as a feature. The Woodstock Poetry Festival, a marvelous although quixotic enterprise, brought a number of major poets to Woodstock for a couple of years. Hearing people who had been only names on a page, like Sharon Olds and Billy Collins, turned out to be inspiring.

One of our best Ulster County poets, Cheryl A. Rice, invited me to a poetry salon she had decided to host. We had only two meetings, but I found those sessions tremendously useful, not only for the feedback I got on my work but also for the way it focused my attention on what was happening in other poets’ work. When Cheryl told me she hadn’t continued the salons because she didn’t want to be stuck cleaning her house on schedule, I invited her to start the meetings up again at my house, since I had a paid house cleaner. Because my house was on Goat Hill Road, we became the Goat Hill Poets, and we still are even though we now meet at Tara’s house in Woodstock.

I was intrigued when I learned that Sharon Olds, one of the poets I most admire, was teaching workshops at Omega Institute in nearby Rhinebeck. Attendance at these workshops was by invitation only, and the first two times I submitted work I wasn’t invited. The third time, though, in 2007, I was invited as an alternate, and someone dropped out. I got to work for a long weekend with Sharon Olds in a small group, ten of us. I thought everyone else wrote better than I did. But for the final session, I wrote a snidely satiric poem about Omega itself. Seeing the whole group, including Sharon, laughing heartily at my work gave me a sense of poet power that I’d never had before.

The following summer I got to work with Sharon and nine others for a full week. It was an incomparably nourishing experience. At the next to last session, she challenged us to write something that was difficult to write. I wrote a poem about my wife Tara and our experiences together, and “My Love” won a prize in the Prime Time Cape Cod poetry contest. It was just honorable mention, but it was $50 cash and a $25 gift certificate to Borders, a lot more than most poets receive for published work.

Unfortunately for me, Sharon has decided to limit her teaching and concentrate more on her own work, so she doesn’t teach at Omega anymore. Last summer, Omega had a very different type of event, a “Celebration of Poetry” hosted by the wonderful Marie Howe, with half-day visits from Mark Doty, Patricia Smith, and Billy Collins. With 91 people in attendance, I wasn’t expecting much. But I was surprised by the excellent experience it turned out to be. Collins, answering a question, said that he could recognize a talented poet by a gift for rhythm and a gift for metaphor. I’ve been surprised over the years to discover that I have both of those.

I’ve been a slacker about submitting my poetry for publication. But I have had a couple of poems published in Home Planet News, a long running poetry paper edited by Donald Lev. My father got to see the first one shortly before he died. I’ve had a few poems published elsewhere, including the Goat Hill Poets anthology issued in 2010 and in an article on the Goat Hill Poets published by Ulster Magazine. Aside from reading with the Goats, I’ve done various features in and around Woodstock, most recently July 4, 2011 at Harmony. (The link leads you to an audio recording.) On February 3, I was one of the featured poets at the excellent Calling All Poets Series in Beacon. A recording of that reading will shortly be available on the series website.

I’m still writing poetry. Unlike some of the really good poets I know, I don’t set aside regular time for writing. The ideas have to force themselves into my awareness for me to pay attention to them. But I’ve learned always to have a pad and pen with me.

(Top photo: Leslie reading in Kingston. Photo by Dan Wilcox.)

Tara, Renee, Leslie, and Gerard at my birthday party

One of the happiest events of my life occurred in March of 1985. I was at work on my Sunday afternoon shift at WDST, trying not to let my gloominess affect what I was saying to my listeners. As a piece of music was playing, I heard the doorbell ring and found my old friend Tara at the front door. I was glad to see her.

Since I’d met Tara, about eight years earlier, she had become one of my best friends, a trusted confidante and someone I admired tremendously. Tall (six foot two) and glamorous, she was about as smart a person as I’d ever met, a prosperous full time professional writer with a wide range of artistic and intellectual interests. She was also real home folks, completely without pretension. Hell, she had taken money at the door the night my one-shot band The Pub Crawlers, with her then boyfriend playing drums, had performed.

Since I had plenty of time before the music ended, I invited her into the air studio and asked what brought her by. Nothing special, she told me, just wanting to know how her friend Leslie was doing. I told her I was not feeling very good. Since a brief but disastrous affair with a bad woman a couple of years ago, I had been recovering only slowly from that awful experience. Recently I’d been dating a woman from New York whom I’d met through the Classical Music Lovers Exchange. It hadn’t been very serious, but she had just broken it off and I was feeling very lonely.

“I don’t know who’s going to want me now,” I said. She grinned. “I do,” she said.

Well, we were both single, and we certainly knew that we enjoyed each other’s company. So we agreed to go out on a real date, unlike the friendly dinners we’d had before. Because I was about to go to England, we made the date for the day after I got back. And because that date was stamped on my passport, I know the exact day of our first date: March 25, 1985. We’ve celebrated that as our anniversary ever since–and we probably will always, even though we actually got married on October 17 of last year.

Within a few months, Tara and I had decided that we were going to be committed to each other. The relationship took a long time to evolve, though. We each had our own houses, and although we spent more and more time together, we didn’t even talk about living together. I think the scabs were still healing on both of us. Still, it didn’t take me long to realize that I was involved in the love affair of a lifetime. From our early days, Tara and I encouraged each other in positive ways. She was very stern about my tendency to be careless with money, to the extent that she once broke up with me over that issue. Our dear mutual friend Charles Elliott, up from Florida for a visit, told both of us that we were crazy to look for anyone else, so after two months we were back together for good.

Although she was far more financially successful than I was, she never made an issue of it and when she decided we should do some traveling together, she insisted on paying more than her share so we could go. At her urging, we took some wonderful trips I would never have made otherwise, to Hawaii, Peru (a magnificent Nature Conservancy tour of the Amazon and the Andes), and Belize. I didn’t like her tendency to work very late. She would often write until 2 a.m. or later (these were always “work nights,” when we stayed at our own houses), but I saw that such late work had a bad effect on her, and eventually I got her to promise she would stop by midnight. She admitted that she felt she got more work done overall that way. When I first got together with Tara, she was still smoking cigarettes. I urged her to quit, and she promised she would. But I still was finding ashes in the toilet bowl. One day when I was at her house, I was looking for something in her office and found an unopened package of cigarettes in a desk drawer. I took it out, put it on the floor, stepped on it, straightened it out, and put it back into the drawer. We never exchanged a word about it, but I never saw a sign of smoking again.

We encouraged each other’s creativity. Although I’d majored in Creative Writing in college, I was doing very little writing aside from my music criticism. Tara encouraged me to get back to it, and she shepherded me through the writing of a novel, which I wrote mostly just to prove to myself that I could get through a book-length project. When I began to write poetry–a strange result of a series of nightmares–she was extremely encouraging and helpful. I knew I could believe her when she said something was good, because when she said just “Needs work” I knew that poem was destined for the recycling bin.

Tara was writing short stories and poems just for herself, but she got involved in a local writing group and let it publish a couple of her poems and a memoir. I talked her into going to Omega Institute to take a writing workshop with Grace Paley. The night after the first session, she told me that Paley had invited the participants to bring in a piece of finished writing for the second day. She showed me a story I had never seen before and asked me if I thought it was good enough to show someone else. I read it and said, “She’s going to tell you to publish it.” “You’re just being my fan club,” she said. “No, I’m not,” I insisted, “and I’ll bet you dinner for two at New World (our favorite restaurant, still) that she says you should publish it.” She took the bet, but I won it. (Paley’s words, she told me, were “This one’s ready to go.”) I got the dinner, but she never did submit the story.

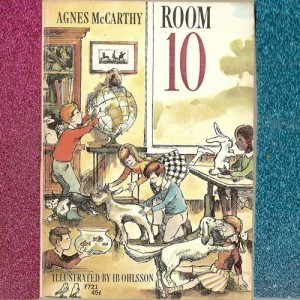

Most of Tara’s writing was for educational purposes, textbooks and teacher guides. Many of them are still in use. But early in her writing career, when she still had her original name of Agnes McCarthy, she wrote a book based on a year’s experience of teaching third grade in Wyoming, called “Room 10.” It was in print for more than 25 years. During one of our visits to Charles in Florida, I accompanied Tara to the large children’s library in St. Petersburg, where she wanted to do some research. She told one of the librarians that she was a writer and needed some help. The librarian asked if Tara had written anything she might know. Tara mentioned “Room 10.” The librarian asked her to wait for a moment, then rounded up all the children’s librarians so they could meet the author of “Room 10.”

When I think back on the good years with Tara, what I remember most is playing a lot. We would sit home and watch a movie. We would go out to see friends. We would go to concerts, movies, theater. (She insisted we go to New York to see “Angels in America,” one of the great experiences of my life.) We had tremendous amounts of fun, the most I’d had since I was raising my step-daughters only it went on a lot longer.

Nine years ago, Tara became seriously ill. A visiting friend of mine, Steve Smolian, pointed out that she seemed in particularly bad condition and urged me to get better medical care than we were getting. After some fumbling doctors dropped a few balls, we finally got a dreaded diagnosis: ovarian cancer. It turned out to be in a very early stage. This “silent killer” had apparently outraged her system, which had reacted violently and given warning. Her surgeon told us the cancer had been in Stage 1C, and that chemotherapy might not be necessary, but he strongly urged it. Then he left his post weeks later, leaving her essentially unsupervised. It took us years and hi-tech tests to discover that while her immune system was suppressed by the chemo, she had fallen victim to a brain infection.

We have both worked very hard to help Tara recover from her injury, and we have had some successes. Unfortunately they have not lasted. Today, she is incapable of living independently and I am her full-time caregiver. She still loves me deeply, and frequently tells me so. But she becomes so frustrated with her own limitations that she gets very angry sometimes, which is hard for someone who loves her as much as I do to witness. I still wouldn’t trade her for any other woman in the world. And we still have plenty of fun together. Only two days before I am writing this, we went to see the Met Live in HD broadcast of Wagner’s “Götterdämmerung,” which lasted with intermissions nearly six hours. We both had a good time.

We still go to lots of movies and concerts, watch “The Daily Show” and “Real Time with Bill Maher” regularly, and do whatever stimulating activities I can come up with. Fortunately, poetry seems to reach her on a level that few other things do, so we go to lots of poetry readings. When I decided we needed to be legally married so that I could do the best possible job of protecting her in difficult circumstances, I was concerned that she might not like the idea or even understand it. But she became very enthusiastic, and her only reservation was, “I thought we were already married.” She was right.

The Considerate Boyfriend

My lover is a very nice lover.

He doesn’t jump on me while I am reading.

He doesn’t paw me at bedtime.

He doesn’t ask me to take my clothes off after I have just finished dressing.

My lover is very considerate and subtle.

Like, when he sees a real hot movie star in a movie,

he just goes, “Wow, look at that!” “Would I like to have a piece of that!”

Then, after the movie, he says, “I hope you didn’t take offense.”

“I mean, she is a 10 definitely,

but you are a ten and a half.”

So eat the pizza slowly, because afterwards

you have to paw him and take your clothes off slowly, just to

show both of you that you are as wonderful

as he thinks the hot movie star is.

“Wow,” he says. “I love an assertive, take-charge woman!”

So you lie there and sigh a lot as he jumps on his dream.

Meanwhile, the movie star is probably reading the script for

her next movie! which you will probably have to suffer through

with this

Considerate Boyfriend.

–Tara McCarthy, c. 1987

The great Polish poet Wisława Szymborska died last week at the age of 88. You can learn a great deal about my own taste in poetry, and ambitions for my own work, when I mention that she was one of my favorite poets ever.

Since Szymborska dealt so profoundly with the life of ordinary things, I’ll start off by telling you how to say her name correctly. That funny symbol of the L with the line through it, which I believe may be unique to the Polish language, is pronounced like a W in English. The W in Polish, as in some other languages, is our V. So her name is pronounced vis-WA-va shim-BOR-ska.

I am not really equipped to write an analysis or appreciation of Szymborska’s poetry. That task has already been accomplished satisfactorily by Billy Collins, in his introduction to “Monologue of a Dog,” the first collection of her work published in English after she was awarded the 1996 Nobel Prize for Literature. (Her friends referred to that event as the “Nobel Tragedy” because she stopped writing for several years after the prize was awarded.) Here’s the quote that appears on the dust jacket: Szymborska knows when to be clear and when to be mysterious. She knows which cards to turn over and which ones to leave facedown. Her simple, relaxed language dares to let us know exactly what she is thinking, and because her imagination is so lively and far-reaching–acrobatic, really–we are led, almost unaware, into the intriguing and untranslatable realms that lie just beyond the boundaries of speech.”

Collins is a profound fellow, despite the conversational nature of his prose and poetry, and he has given a good definition of poetry here, at least poetry as I conceive of it: “realms that lie just beyond the boundaries of speech.” That’s why I cannot summarize one of Szymborska’s poems–not only because they are so concise, but because in their selection of images, their unconventional thoughts, and their precise expression, they are indeed beyond the boundaries of speech. That paradox–using words to express what lies beyond words–is the nature of great poetry. Szymborska travels in that land very often, and in moving and surprising ways. And although I read her only in translation, I feel that I do understand what she is getting at. The concepts come across.

Although half of “Monologue of a Dog” is wasted on us because it includes the Polish originals of the poems as well as translations, I still recommend it as an introduction to her work. If you want to see how this modest woman, working in obscurity as an editor at a Polish literary magazine, developed her unique voice, you can get either of the earlier English language collections, “Poems New and Collected” or “View with a Grain of Sand.” Both volumes include a lot more poems than “Monologue of a Dog,” and both include many examples of the work Szymborska did–including much rhyming verse–on her way to mastery. But “Monologue of a Dog” is all masterpieces. It includes the great title poem, which shows how the choice of a limited perspective (a dog’s) on human activity illuminates human experience; “A Few Words on the Soul,” as amusing as it is a profound exploration of human nature; and the heartrending “Photograph from September 11,” in which a few words recreate the awful experience of that day with the most beautiful compassion and sorrow. These poems are magic tricks as much as they are explorations of the experiences we share.

If you don’t know this magnificent poet, even if you are usually not a poetry consumer, take a few minutes to read some of her work. These poems may not change your life the way they have mine, but the will put you in touch with one of the most beautiful people ever to walk our planet.

You can find out more about Wislawa Szymborska on the Culture.pl page about her at http://www.culture.pl/web/english/resources-literature-full-page/-/eo_event_asset_publisher/eAN5/content/wislawa-szymborska