I had no hint from the announcement that an intense new love affair awaited me. It was called “A Performance Unwritten,” for an event on May 31 at a venue called MAMA Arts in Stone Ridge, New York. Its premise was that artists in various media and forms, most of whom had never worked together before, were going to create an evening of entirely improvised art. Well, no thanks, but that doesn’t sound like my bag, man…

…except that my poet friend Judith Kerman was one of the artists involved. And it was on an evening when I had nothing else planned. And it might be something that my wife, who has Alzheimer’s Disease, would enjoy, since it sounded as though it would be visually stimulating and she usually enjoys music.

When we got to Stone Ridge, my suspicions were immediately aroused by the venue. I’d never been there before, and it didn’t look like a very well-organized place. But the event attracted a fairly good-sized audience, and as soon as the trio of musicians started to play I knew I was in for an enjoyable evening, since they were quite good. As the performance progressed, some of the spoken word improvisations were involving (especially, I must say, Judy’s), some less interesting, but the music kept things lively.

And then there were the painters, one on each side of the hall. One of them was doing some pretty interesting work. The other looked at first as though she was just splashing and dabbing paint on a large black board, using several methods to get paint onto the board not including a brush. Just as I decided the work was going to be nothing but abstraction, she put her hand into white paint and pressed it down, and as she lifted it off I realized that her handprint was at the end of an arm and she was creating a figure.

That moment of recognition threw a shock into my system. I was reminded of the time, half a century ago, when I heard my first Cecil Taylor record. A jazz critic friend played it for me, telling me he thought Taylor was the next great thing in jazz. I listened with increasing puzzlement as some guy seemed to be throwing his hands at random around the piano keyboard, until I suddenly realized that an impossibly complex figure ran up and down the keyboard and was then repeated exactly. The understanding that Taylor was in complete control of everything he played forced me to listen with different ears.

I had that same realization about the work of Nancy Ostrovsky. Throughout the remainder of the performance I couldn’t take my eyes off her. After she finished the first painting, she took it off the easel, rested briefly, and then started throwing paint around again. This time, she was creating a picture of the musicians and some dancers who briefly participated in the performance.

It was art love at first sight. At the end of the performance, I rushed over to Ostrovsky and asked how much she wanted for the paintings. The price she quoted seemed quite reasonable. I handed her some money as a down payment on the one I had decided I wanted. (It turned out, not surprisingly, to be a little less than it’s costing me to frame it!)

Perhaps I should have bought the figure. It was the painting that gave me that thrill of discovery. But I decided I would have more fun looking at the musicians. I look forward to having them as companions for a long time, and to seeing a lot more of Nancy Ostrovsky’s work. When I went to her studio to collect my painting–she wouldn’t let it go immediately because she wanted it to dry properly–I saw a lot more of her work. One impressive item was a copy of a poster for a Dizzy Gillespie concert, inscribed to her by Gillespie.

This is an original song, from a large group of songs I wrote and performed in the mid-1980s. It comes from a concert at a local store, Just Alan, on Route 28 in Shokan.

Press the play button to hear “Isn’t It Fun” written and sung by Leslie Gerber at Just Alan, 1985.

When I was a young man, I became friends with an elderly violinist named Jerome Goldstein, a customer at the bookstore where I worked. I never had the curiosity to discover his distinguished background.

In 1964 I dropped out of Brooklyn College and married a whole family, a woman with three children. In order to support us, I took a job at the Strand Book Store in Manhattan, which was then probably the largest used book store in New York if not the whole U.S. While far from its present total of two and a half million books, it was already large enough to require a full-time book cataloguer, which I became. I worked there for five and a half years before moving to Ulster County in 1970, where I still live.

Any book store buying entire collections is going to wind up with nearly valueless books. The Strand disposed of these on outdoor stands. Several times I encountered an elderly man going through the 10 and 25 cent books with great diligence, and we got to talking. When he found out I was interested in music, he told me he was a professional violinist. His name was Jerome Goldstein.

I usually left work as soon as possible to get home to my wife and family. But Jerome started inviting me to visit him, and eventually I put aside an evening for the visit. He lived in a huge rent-controlled loft, just around the corner from the Strand, on Fourth Avenue. On that first visit I met Jerome’s wife, who seemed to be perpetually angry, and saw the pseudo-splendor in which he lived. The walls were crowded with book shelves and music shelves. A somewhat deteriorated grand piano was almost hidden by piles of tattered books and papers.

When I left that evening, Jerome gave me a pie in a box and told me to take it home to my family. I was suspicious of it, and when I got home I made sure to open it after the kids had gone to bed. It was moldy, probably given to him by a bakery near the end of its expected lifespan.

Jerome told me he had played with the Philadelphia Orchestra when Stokowski was the music director. I figured it was probably true, and it was; the orchestra’s website lists a violinist named Jerome Goldstein who was a member from 1917 until 1921. But he seemed like such a crackpot, although a likeable one, that I found it hard to take him very seriously.

One day he invited me to join one of his evening musicales. I had admitted to him that I played the piano but insisted that I wasn’t very good at it (the truth) and that I had neither the technique nor the experience to play chamber music. But I did mention that I played the first Prelude from Bach’s “The Well-Tempered Clavier,” so he told me to come and play that and that he would play the “Ave Maria” melody that Gounod had fitted to the Bach Prelude.

I don’t remember that we had any rehearsal. When I arrived at Jerome’s apartment that evening, I was surprised to find a rather large audience assembled, at least 50 people. Jerome played some unaccompanied violin music first, and as I expected he didn’t sound at all good. Whatever violin he had played in Philadelphia must have been long gone, and the scratchy sound he drew from his cheap fiddle was hard to take. I suffered through the Bach-Gounod, which I didn’t like anyway.

I continued to see Jerome for another year or two, until he became ill with lung cancer. I visited him in the hospital near the end of his life, and brought away an image which comes back to me whenever I see someone smoking. He was lying in bed, feeble and incoherent, until he thought he saw demons coming at him through the walls. Then he sat up and started screaming at them.

After I left New York, I hardly thought about Jerome until one day when I was looking through a book on Charles Ives and was startled to see a photo of Jerome. The caption indicated that he had been involved in early performances of Ives’s music, sometimes with the composer at the piano. (As his private recordings reveal, Ives was a virtuoso pianist.)

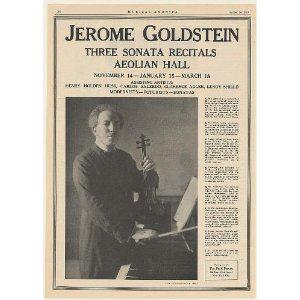

The photo above is from an ad for a series of three morning recitals, with pianist Rex Tilson, given at Aeolian Hall (the place where the “Rhapsody in Blue” was first performed) in 1924. An unsigned review of the last concert, published in the New York Herald Tribune, mentions performances of works by Ives, Milhaud, and Pizzetti, giving “the palm to Pizzetti.” The Ives work was the Fourth Violin Sonata, composed in 1909 and not published until 1951. This was its premiere performance.

The Ives book also mentioned that Jerome had performed with Béla Bartók during the composer’s first tour of the United States in 1926. Doing some quick Internet research I turned up only one other reference to Jerome. He played Henry Cowell’s “Solo for Violin” (with pianist Imre Weisshaus) at a concert of the Pan American Association of Composers at “Carnegie Chamber Hall” (probably the small theater now known as Weill Hall) on April 21, 1930.

I’m sure Jerome was involved in many other interesting events like these. And I wish my callow younger self had had the sense to ask him about his career. I never did.

Recently at Maverick Concerts the Music Director, Alexander Platt, introduced Ravel’s “Gaspard de la Nuit” and mentioned that Ravel was a “great virtuoso pianist.” This is a common idea but it’s wrong, interestingly wrong.

According to the accounts I have read, Ravel was not a particularly devoted piano student during his conservatory years. What efforts he did extend were mostly towards developing his compositional technique, which remained a lifelong obsession. “My objective,” he once wrote, “is technical perfection. I can strive unceasingly to this end, since I am certain of never being able to attain it. The important thing is to get nearer to it all the time.” Ravel also made unusually detailed studies of the capacities and qualities of musical instruments, which resulted in his becoming a great master orchestrator.

Ravel became merely a competent pianist. He was unwilling to put in the endless hours of practice that would have made him a virtuoso, and we are all the better for that. Certainly it would be useful and inspiring to have recordings of Ravel playing his own piano masterpieces–if he could have played them well. But he couldn’t. He rarely if ever played them in public, and he never played his piano concertos.

Ravel is not the only composer who was unable to play his own compositions. Henry Cowell’s widow once told me that her husband did OK with his avant-garde piano pieces (some of which he recorded successfully) because they weren’t very difficult to play. But he couldn’t play the piano part of his Violin Sonata when it was recorded. There are many stories about how Robert Schumann ruined a potential career as a virtuoso when he damaged his hand using a machine intended to increase the independence of his fingers. But Schumann had never been a serious piano student and never planned on a virtuoso’s career.

In all of these cases, the composers understood the technique of the piano well enough to write in innovative and imaginative ways for it. I can sympathize with how this works. In my own piano playing days, I would sometimes read through such demanding pieces as Prokofiev’s Toccata or Brahms’s arrangement of the Bach Chaconne for left hand alone. I couldn’t have played these pieces if I had practiced them for years. But I was able to learn how they worked.

During Ravel’s lifetime there was enough demand for his music so that recordings by the composer would have sold well. This demand led to two instances I know of in which recordings were deliberately and fraudulently presented as Ravel’s own when they were not. Ravel’s only recordings as a pianist were as accompanist for the singer Madeleine Grey. He never made records of his solo piano works. He did make some piano rolls, a medium in which mistakes were easy to correct. But the pianist Gaby Casadesus admitted years after the fact that when the more difficult Ravel pieces were recorded on piano rolls her husband Robert had done the playing, and the Duo-Art company issued them under Ravel’s name.

Ravel wasn’t a very accomplished conductor, either. He made only two recordings as conductor, and they are valuable for their musical insights. (More on this in a moment.) But when the French branch of HMV recorded his Piano Concerto, with the pianist for whom he had written it (the wonderful Marguerite Long), they hired the Portuguese conductor Pedro de Freitas Branco to conduct the pick-up orchestra and put Ravel’s name on the records as conductor. The deception was uncovered many years later, in the company’s archives. (Freitas Branco was credited as the conductor of the “filler” on side 6 of the 78 rpm set.)

So what is the value of Ravel’s recordings? Obviously, the atmosphere in the song recordings is authentic, and Grey was a superb singer. One of the recordings of Ravel conducting, his “Introduction and Allegro,” is an acoustical recording, made in England in 1923. Its fidelity is limited, and the English musicians involved were probably not very familiar with the music or the style, so it’s not a great experience.

However, Ravel’s other recording, “Boléro,” made in 1930 with the Lamoureux Orchestra, is a revelation. Technically, it’s not very accomplished. Although the orchestra was one of France’s best, it doesn’t play with fine precision, probably due to the limitations of the conductor. But the musical interpretation shows us what Ravel intended in his repetitious work, and it’s not as boring as it usually sounds. Ravel was famously quoted as saying, “There is no music in it.” But the slow tempo he takes allows the scoring to sound in a most convincing way, and the inflections he draws from the solo instrumentalists are fascinating. Apparently the conductor Riccardo Muti feels the same way I do, because his EMI CD of “Bolero” is a close copy of Ravel’s interpretation.

Obviously a composer doesn’t have to be able to play or conduct all of his or her own music. That doesn’t take anything away from the music, of course. I do love to hear composer-virtuosi, like Rachmaninov, Prokofiev, Sarasate, Leon Kirchner, and others, performing their own works. But I’ll never hear Bach perform and I still love his music.

On the Saturday night of Memorial Day weekend, Tom Pacheco gave one of his occasional performances in Woodstock, his home town. The Colony Café, as usual for his shows, was jammed. And we got more than our money’s worth.

I’ve known Tom slightly since my days in Phoencia, almost four decades ago, when I used to hear him sing at the White Water Depot in Mt. Tremper (to the left, Tom backstage at the WWD with Tiny Tim) and played pinball with him. (I was a pretty good player on the pinball machines of that era, although Tom usually beat me.) He was away living in Europe (where he still does most of his performances) for a decade. Since he returned to Woodstock, I’ve done my best to catch every show he does.

Tom is a powerful performer and a powerful songwriter. He covers the usual songwriters’ topics–love, lost love, friends, mortality–but adds a strong dose of social commitment unusual in contemporary music. When I hear contemporary “anthems,” songs about our people and the world we live in, they tend to be maudlin and embarrassing. Not Tom’s! He can write a song like “There Was a Time” without sentimentality or haranguing, but it still carries a great deal of power.

When you sign onto his website, you get him singing “Big Muddy River,” a song reminiscent of Pete Seeger’s “Waist Deep in the Big Muddy” except that it really is about flooding and also about politics. (Seeger played banjo on two tracks of Tom’s album “There Was a Time.”) You can hear right away how powerfully Tom performs, and how urgent his communication is. (I once complimented him on his diction, and he told me he works at it a lot.) His guitar playing is strongly rhythmic and compelling. And he even manages to play occasional harmonica without sounding klutzy.

Reading a profile of Tom in last week’s Woodstock Times, I was unsurprised to see that he is a very prolific songwriter. There are always a few old favorites in his shows–“Blue Montana Sky,” “There Was a Time,” “The Hills of Woodstock,” “Solidarity”–but most of the material is new or recent. Sometimes the songs have some rough edges, a line or two that doesn’t work quite right, an image that doesn’t quite fit. He must have gone on to the next song. It doesn’t matter. They still work.

One of the newer songs in Tom’s performance was a tribute to Woody Guthrie. It was completely appropriate. Tom is, in my opinion, the closest thing to Woody Guthrie I know on the current music scene, except that he plays guitar a lot better than Woody did.

Being so prolific, Tom has recorded many albums. The two “Secret Hits” compilations are good places to start getting acquainted with his songs, and of the two I’d try Vol. 2 first. But in any Tom Pacheco recording, as in any performance, the guy’s passion and commitment always come through vividly. He’s one of my favorites, and maybe even one of my heroes.

It was back in the early 1980s. I saw a few small posters–just 8 ½ X 11 sheets–advertising a piano recital in Woodstock by somebody I had never heard of named Morey Hall. He was playing at the Kleinert Gallery, the most prestigious year-round concert venue in Woodstock. But I saw so little publicity for this concert that I suspected he had just hired the place.

I was already writing classical music reviews for the Woodstock Times, and I could have tried to get in touch with someone to get free tickets. But I had an uncertain feeling about this event. So I decided to go and buy my ticket, and if Hall was surprisingly good, I would write about him. My girlfriend Anne and her son Greg, both musicians, went with me.

When we got there, about 15 minutes before concert time, we found two people who had obviously come with Hall, taking money. Nobody else was there. By concert time, two more people had drifted in. So the concert started with seven people in the audience.

The program begin with a baroque suite by the obscure composer Domenico Zipoli. Within seconds it became apparent that Hall couldn’t play worth a damn. The music was quite simple, but even at his cautious tempos he halted and fumbled and made a mess out of everything. The rest of the first half of the program was Schumann’s Fantasy Pieces, Op. 12, music written for a virtuoso pianist. Hall played through the more difficult pieces at around half their proper tempo, but still continued to fumble. It was really painful.

At intermission, Greg and Anne and I went outside so Anne could have a cigarette. As she smoked, I asked the dreaded question: “Are we going back in there?”

“We can’t leave now,” said Anne. “We’re almost half his audience!”

“I know,” I said, “but do we want to hear what he is going to do to Schubert?”

“Right,” said Greg. We left.

This performance was a “tryout” for a recital Hall was about to give at the Albany Institute of History and Art, an institution I have regarded with the greatest suspicion since I heard Hall. My friend Rich Capparela was working at a radio station in Schenectady and living nearby, so I did my best to trick him into going to the concert. He couldn’t make it, but he did some investigation and learned that Hall was studying with Findlay Cockrell, one of the best pianists in the area. He heard that Cockrell had once told Hall not to come for any more lessons, and that Hall had camped out on Cockrell’s front lawn until Cockrell relented.

That was my last thought of Morey Hall until about ten years ago, when I met Cockrell at a recital. A mutual friend introduced us. “Oh, yes,” I said, “the teacher of Morey Hall.” Cockrell looked daggers at me until I started to laugh.

After I explained that I had heard Hall and that he had my full sympathy, Cockrell told me a story about Hall. Through Christian Science circles, Hall arranged an invitation to play for the great pianist Malcolm Frager, who lived less than an hour away from him. Frager listened to Hall play his entire concert, and then said, “Good. Now go home and don’t ever play the piano again.”

There are two aspects of this story that interested me greatly. One was that I had met Frager and found him a very kind man. The other was that Cockrell knew of the incident. There was no way he could have learned it unless Hall had told him.

Hall was a horrible musician, but the worst classical music performer I ever heard was William F. Buckley, Jr. Yes, that William F. Buckley, Jr. Buckley studied the harpsichord for years with the great harpsichordist Fernando Valenti, and he wrote an article about his studies which I read somewhere, probably in the New York Times Magazine. Buckley had become acquainted with Leon Botstein, President of Bard College, and had invited Botstein to be a guest on his TV show “Firing Line.” Botstein, in return, invited Buckley to perform with the Hudson Valley Philharmonic Chamber Orchestra, which he had created and of which he was music director.

Buckley’s participation in the program was curious indeed. He was scheduled to play Bach’s solo “Chromatic Fantasy” (but not the difficult fugue which follows it), then the second and first (of three) movements of Bach’s Concerto in D Minor, in that order. This, I thought, is someone very much aware of his own limitations.

But I was wrong. Buckley couldn’t come close to playing even the easier music he had selected. During the “Chromatic Fantasy,” there were long stretches of the piece in which he played more wrong notes than correct ones. In the Concerto, the orchestra covered some of the musical transgressions–especially since Botstein, highly inept himself at this early stage of his conducting career, had no idea of how to balance an orchestra with the quiet harpsichord. But you could still hear enough to tell it was a disaster. I was amused to see Buckley moving his head closer to the music and squinting as if somehow seeing the notes more clearly would help him play them. It’s a gesture I’d often seen in children’s piano recitals.

Whenever I hear a musical performance I’m not fond of, I think back on these events and sigh.

Recently I’ve been listening to two Russian classical pianists from very different eras. Vladimir Feltsman is still in his prime. Vladimir de Pachmann was one of the earliest pianists to make records. I love them both.

I was involved in the Vladimir Feltsman story in a small way. After he applied for an exit visa to leave the Soviet Union with his wife and son in 1979, he immediately became a “nonperson.” Not only was the application refused, but his career was shut down. He had already toured outside the Soviet bloc, but foreign booking agents were told he was not available for touring. He was forbidden to perform anywhere for two years, after which he was gradually given demeaning assignments like playing a recital in a kindergarten classroom on an upright piano at 10 a.m. His Russian LPs were suppressed and recordings of his concerts disappeared from the Soviet radio archives.

Various Western musicians took up Feltsman’s cause, without immediate results. Daniel Barenboim organized a tribute to Feltsman at Carnegie Hall, at which he and several other famous pianists performed. For the last number on the program, the spotlight was shone on the vacant piano while one of Feltsman’s recordings played.

As a fortunate byproduct of my work as a classical record dealer, I found two of Feltsman’s suppressed recordings in 1984: one original Soviet LP, the other a reissue on a Spanish cassette. (I have since obtained all of them.) At the time I was doing regular classical music broadcasts over WDST in Woodstock. I told Jerry and Sasha Gillman, owners of the station, that I had these suppressed recordings and wanted to do a special. Jerry suggested we attempt to get an interview with Feltsman. I expressed skepticism, but I should have known Jerry better. He called our local representative, Matt McHugh, who in turn got in touch with the State Department. Eventually we heard from the U.S. Ambassador to the Soviet Union, who turned out to be friendly with Feltsman. Sure enough, we got our interview, recorded off the phone from his apartment in Moscow. The resulting program went out on our station, then WQXR-FM in New York and a little later over the Voice of America.

The president of the closest major educational institution, Alice Chandler of the State University of New York at New Paltz, heard about the broadcast. The following month, she and a group of American university professors traveled to Russia to visit with “refuseniks,” people who had been refused permission to leave the U.S.S.R. Chandler met Feltsman at his apartment, and told him if he could ever leave she would offer him a job at her school. He joked with her that if she could get him a false passport he would go immediately.

He was finally allowed to leave in 1987, due to continuing intervention from our State Department and specifically the Secretary of State George Schultz. Feltsman eventually learned that he and several other refuseniks had been released in exchange for some concession by the U.S., but he never found out what that was.

I was among a group of people who met the Feltsmans when the arrived in the U.S. I remember vividly his four-year-old son Daniel running into the press room at Kennedy Airport bouncing a helium balloon on a string and yelling “Mickey! Mickey!” (It was Mickey Mouse.) I didn’t get to hear Feltsman’s first performance in the U.S., at the White House. (I did eventually get a tape of it for broadcast on WDST, the only U.S. outlet that got to run it.) I did hear his official debut at Carnegie Hall, which confirmed what the recordings had suggested: he was a major pianist, with a wide range of abilities and the versatility to play almost anything convincingly. I was particularly impressed with the way he played excerpts from Messiaen’s “20 Views of the Infant Jesus,” with such color and conviction that the audience was transported.

Over the intervening quarter of a century, I have heard Feltsman numerous times, occasionally in New York, more often at the college. Last weekend, as part of the inauguration ceremonies for the college’s new president, and to celebrate his 25th year there, Feltsman played a brief benefit recital at the college. Perhaps by accident, more likely on purpose, Feltsman invited comparisons with the great Sviatoslav Richter, whom he heard in concert many times. He played Mussorgsky’s “Pictures at an Exhibition,” one of Richter’s most famous triumphs. The two other works on the short program, by Schubert and Liszt, were pieces also included in Richter’s most famous recording of “Pictures” (from 1958 Sofia concerts).

I’ve always admired Feltsman’s playing. As a Bach player, he is simply unequalled among those I’ve heard. One of the many fine features of his Bach is his ability to add embellishments to repeated sections of the music, a necessity in Bach’s day but a rarity in ours. Little improvisations like that were expected in performances up through the time of Mozart and even beyond. We know that Chopin often varied his music when he played it. The few grace notes that Feltsman added to his Schubert Impromptu were nothing radical, but they showed the way he thinks about music–creatively.

Feltsman has never been a “black and white” pianist, as his very colorful Messiane playing demonstrated at my first hearing of him. But after hearing his Liszt and Mussorgsky, I feel he has widened his color pallette over the years. The shading in these works was actually reminiscent of Richter.

Creative interpretation was also a part of the style of Vladimir de Pachmann, who was born in 1848 and began making records in 1907. Pachmann has been one of my favorite pianists since I first heard him, more than 50 years ago, in an LP anthology of great Chopin players of the past.

It’s difficult to listen to Pachmann today. Most of the recordings are acoustical (done through a horn, before microphones came into use). They have limited frequency range and, usually, heavy amounts of surface noise. But that’s never stopped me from marveling at Pachmann’s performances, free in a way that would not be acceptable in today’s concert halls but always convincing and expressive. If I had to use one recording to exemplify eloquence and poetry in classical performance, it would probably be Pachmann’s playing of Chopin’s Nocturne in E Minor, Op. 72, No. 1. Despite the late opus number this is actually early Chopin, published posthumously, and it may not be exactly Chopin’s greatest music. But it’s the best sounding of Pachmann’s recordings, and one of the few among his last discs that shows the pianist completely in control.

You can hear that recording for free on the Internet. But if the idea of hearing romantic piano music (mostly Chopin, but also Liszt, Mendelssohn and others) played by a survivor of the romantic era appeals to you, there is a unique opportunity available now. The Marston label has issued a four-CD set of the complete surviving recordings of Pachmann, including quite a few that were never published on 78s. For years I have been dreaming of owning such a set, and now that it’s available, it has been done the way I wanted to hear it. That Chopin Nocturne, for example, should have been heard in clear, fairly wide-ranging sound. It was published on RCA Victor’s best shellac material (the so-called “Z” pressings). But all the previous reissues of it I have heard were sonically dull, filtered to remove surface noise. Marston’s edition is what I’ve always wanted. And for the asking price, it strikes me as a real bargain.

I was probably the least talented and least able piano student Piero Weiss ever had. He got stuck with me in 1969, when I was living on Staten Island. I had found an excellent piano teacher who lived just a few blocks from my house, but her husband got a job in Los Angeles and they moved away. Thinking cleverly for once, I wrote a letter to Jacob Lateiner, a pianist I greatly admired but did not yet know. (Later he became a friend.) I described my level of ability as honestly as I could and asked him if he could recommend a teacher who would take me. He recommended Piero Weiss.

Mr. Weiss, as I called him in those days (later we became Leslie and Piero, but only after I was no longer his student) must have found me a trial as a student. I had no hopes or ambitions of playing on anything near a professional level. As a young man with a wife and three children to raise, I was lucky if I could manage an hour a day to practice, and often I couldn’t. But I came for lessons faithfully every other week, even after I moved to upstate New York the following year. Although I was a poor student, I was otherwise well informed about music, already writing professional record reviews. So even though I was unable to put my knowledge into practice very well, I must have been interesting enough to keep him willing to teach me.

Piero actually taught me more about playing the piano than I had any right to know. I was unsatisfied with the sound I usually produced from the piano. He taught me to listen, assuring me that conscious attempts to alter my sound would probably not work but that concentration on listening would lead my fingers to produce something closer to what I wanted to hear. He also showed me some elements of the technique he had learned from his own teacher Isabella Vengerova, of which I remember the use of the wrists to produce changes in volume, especially strong accents.

One of the aspects of his teaching I particularly remember was the way he would help me select repertoire to study. He often made suggestions. When he asked if I ever had played Schubert and I said I hadn’t, he said, “What’s the matter? Don’t you like Schubert?” “I love Schubert,” I replied. “That’s why I don’t want to play his music.” But he selected for me just the right Impromptu to fit my technique. When I mentioned something I would like to play, he would zip through the score from memory, no matter what it was, and tell me whether he thought I would be able to play it or not. I did surprise him once. I said I wanted to play Beethoven’s Op. 10, No. 2, and he said I would not be able to handle the finale. I worked like a demon for two weeks and came back with that movement comfortably in hand. He was surprised, and gratified.

Piero frequently played for me at lessons, usually just brief excerpts to show me how something should go. He was obviously a superb pianist, and I asked him why he had not pursued a career as a performer. He told me he didn’t have the confidence. But he played me with pride the recording of his performance of the Mendelssohn First Piano Concerto from a Lewissohn Stadium concert. And he gave me a duplicate copy of one of the two LPs he had made for the German record club Opus. I found the other one decades later.

After one lesson, we somehow got into a discussion of the Schumann Toccata. “I used to play that,” he told me. He was still sitting at his piano, and he turned to the keyboard and began to play. He played superbly, with great power and fluency and surprising accuracy. When he had finished, he looked at me and said, “I haven’t played that in twenty years.”

After I “mastered” the Schubert Impromptu to the best of my ability, I asked if he thought I could learn one of the Schubert Piano Sonatas. I was particularly interested in the little Sonata in A Minor, D. 784. He pointed out to me that the finale was beyond my ability, and then told me he hated to teach that piece anyway. He had once had a talented woman student who wanted to play that Sonata. He had told her that the last measures of the finale, in octaves, were very difficult, and that she could not play the movement any faster than she was able to play the octaves because it was improper to slow down for them and spoil the momentum of the music. When she played the Sonata for him, she did slow down for the octaves, and he told her she could not play the music like that. She became angry and never returned.

At one point I fell in love with the Brahms Intermezzo in B Flat, Op. 76, No. 4. Piero encouraged me to give it a try. It didn’t really suit my limited ability, and although I could get through the notes, I was not able to make the piece flow. He kept encouraging me to work on it, but I brought it back for several lessons and it never sounded right. At one lesson, after I lumbered through the piece, I told him I wanted to give it up. “No,” he said. “Work on it for two more weeks, then play it for me and then you can give it up.” I did my best, but the day before the lesson it still sounded lumpy. I came in and said I was ready to quit and didn’t want to play it even the one more time. He told me to try it anyway. I did, and amazingly, that time, I played it very well. When I finished, he said, sounding very surprised, “That was beautiful!” “I know,” I replied, just as surprised. I never played it again. Thinking about the experience later, I suspected that he was not surprised at all. He knew exactly how to push me–like the zen master who told a student in search of enlightenment that if he did not succeed within three days he should kill himself.

I had the opposite experience when I attempted a speedy Scarlatti Sonata, K. 545. I worked hard on it and came to my lesson confident that I would be able to play it quickly and accurately, and I did. When I finished, he looked at me and said, “Mr. Gerber, that is the worst thing you have ever played for me.” It sounded cruel, but he was right; I had just gone for speed and accuracy and forgotten that I was playing a piece of music. He helped me learn to shape the piece so that even at rapid tempo it still made musical sense.

One incident that occurred during our relationship made a lasting impression on me. After a lesson, Piero told me that he had learned about a German musicologist named Wolfgang Boetticher (not to be confused with the cellist and conductor Wolfgang Boettcher) who had been invited to speak at a conference in the U.S. on Robert Schumann. There was no doubting Boetticher’s credentials as a Schumann scholar; he had edited the Henle Urtext of Schumann’s piano music. But Piero also knew that during the Nazi era Boetticher had worked for the government to help locate and identify collections of music and music materials owned by Jews so they could be confiscated. Apparently he was also a member of the S.S. Piero passed elements of the story along to his friend Anthony Lewis, then a regular columnist for the New York Times. After Lewis wrote a column about Boetticher’s background, the invitation was withdrawn. Piero was very proud and pleased, and I learned something about the strength and conviction of this gentle man.

I had relatively little contact with Piero as musical scholar, although I still have my inscribed copy of the book of composers’ letters he edited. I did take a lesson once at Columbia University, where he was teaching, and I got to meet his office mate, Richard Taruskin, who later became a regular customer of my mail order record business. We had some conversations about Italian opera, a favorite topic of his and not one of mine. Although I had grown up in an opera household, and attended occasional Met Opera performances from the age of ten on, I had never become a real devotee of the opera. Piero did his best to convince me of the greatness of Verdi, but it has taken me until recent years to realize how right he was. I am still not convinced by his arguments in favor of Franz Liszt. Piero insisted that all of his music had to be taken seriously, but I still think Liszt wrote both masterpieces and bombastic trivia.

Eventually, not even Piero’s encouragement could keep me at the keyboard, and I reluctantly gave up my lessons, my piano study, and even my piano. But we remained in touch over the years, mostly with occasional phone calls. After he went to Baltimore to teach at Peabody, he told me with great pleasure that he had gone back to playing the piano in public and was performing at faculty recitals. Earlier this year, I spoke with him several times after our mutual friend Jacob Lateiner died, telling him that I was working on publishing a Lateiner memorial CD set. I last spoke with Piero a month before he died, telling him that publication of the Lateiner set was imminent. I regret that he never got to hear it.

I was already a fan of Richard Thompson before the first time I heard him in person. That event occurred in St. Petersburg, Florida, more than 20 years ago. My wife and I were vacationing in the area and when I heard that Thompson was playing I had to go to hear him.

I was already a fan of Richard Thompson before the first time I heard him in person. That event occurred in St. Petersburg, Florida, more than 20 years ago. My wife and I were vacationing in the area and when I heard that Thompson was playing I had to go to hear him.

When we arrived at the venue we were considerably unimpressed. It was a seedy-looking bar with a total of one chair in the entire place. We got there early enough to secure that chair, where my wife sat sipping white wine and waiting for something worthwhile to happen.

That took quite a while. The show started late, and opened with a local woman folksinger who had nothing worthwhile to offer. After a few minutes, my wife Tara started looking at me and mouthing, “Let’s get out of here.” I insisted we wait. Once Thompson began singing, Tara took my hand and beamed.

Since then, I’ve heard Thompson in three different nearby venues. He performed once with his band at the Bearsville Theater, which seats about 250 people, three miles from my home. The place was packed. He’s also performed once at the Bardavon 1869 Opera House in Poughkeepsie–the theater where Ed Wood got his start in movies, as an usher. That place seats almost a thousand people, and it too was full. Most often, we have heard him at The Egg, a complex of two theaters in Albany. He performed, with and without his band, at the larger Carlisle Theater, which also seats almost a thousand (and has no bad seats). The hall was never sold out, but it was usually about 90% full.

The hall was about 90% full when Thompson performed his solo act there on October 13. But after being announced for the Carlisle Theater, he was moved to the Swyer Theater, less than half the size of the Carlisle. This seems to be a drastic falling-off of attendance since the last show, by about half. Perhaps most Capital District Thompson fans prefer the band, although I’ll never go to see it again. The last time, although the performance was spectacular, the volume was so loud it hurt my ears. (In correspondence I learned that The Egg’s director agreed with me but blamed the traveling sound man who came with the band. Well, nuts. It’s not his theater.)

Then again, maybe the problem was that Thompson was performing the following night at the Mahaiwe Theaterr in Great Barrington, Massachusetts, about half an hour away….

Still, what is there left to say about this man? Probably nothing new, but I’m inspired to rehash anyway. I think Richard Thompson is one of the most remarkable performers I’ve ever heard. Usually, when I hear a singer-songwriter-instrumentalist, one of those aspects is most outstanding and the others follow behind. Not with this guy! He is one of the greatest guitar players I have ever heard, and he’s not limited by any genre. While he does have a basic folk style, he plays it with more elaboration and virtuosity than anyone else I can think of, and he’s just as adept as a rock guitarist. (Some day I’d like to hear him try a movement of Bach. He obviously has the chops.) In one of his performances at The Egg, an obscure but highly amusing Frank Loesser version of “Hamlet,” he gave a convincing impersonation of a 1940s jazz guitarist. He sings with tremendous power and range, with breath control an opera singer might envy, and his diction is among the clearest I’ve ever heard. And as a songwriter, he is one of the geniuses of his time. Many other performers use his songs, often to great effect, although it’s rare that anyone can outdo Thompson in his own material. His lyrics are memorable, and his melodies are accompanied by harmonic and rhythmic complexity far beyond the ambitions of most songwriters.

At this show, I was especially struck by a song called “Pharaoh,” which sounded as though it had been written as a theme song for the Occupy Wall Street movement (which I had joined, although at Wall Street in Kingston, New York, earlier the same day.) It wasn’t until I got on line that I discovered the song was first recorded in Thompson’s album “Amnesia” in 1998!