My specialized knowledge of Christmas music came about because I am Jewish. In 1980, my first year on the air at WDST in Woodstock, the management asked for a volunteer to run the Christmas eve airshift. Nobody else wanted to do it; they all had places to be on Christmas eve. I didn’t care, so I volunteered.

When I do things, though, I like to do them right. So, with several weeks’ notice, I set about putting together a collection of good Christmas music. Since my own tastes are very eclectic, I decided that the widest variety of music I could play would make for the most fun. And anyway, who would be listening to the radio on Christmas eve?

So, I searched my memory for outstanding examples of Christmas music. I’ve always loved the gorgeous melody and irregular phrases of “Lo How a Rose” by the great early baroque composer Michael Praetorius, so that went in. “Silent Night,” of course, is a gorgeous inspiration, the only surviving composition of Franz Xaver Gruber (1787-1863). But I had to find a non-corny performance of it. One of my favorite Christmas song recordings ever is a version of “Children Go Where I Send Thee,” retitled “Holy Babe,” sung by a group of convicts at Cumins State Farm, Arkansas, in 1942, one of Alan Lomax’s field recordings. It’s still been issued, as far as I know, only on a Library of Congress LP called “Negro Religious Songs and Services,” but I had a copy. (Because it runs so long, the original recording was on two 78 rpm disc sides, and that division was preserved on the LP dubbing. But someone at the station copied it onto an open reel tape for me and eliminated the break between sides, and I used that for the next decade.)

When the evening arrived, I went on the air at 7 p.m., prepared to go until midnight with the material I had on hand. But I also took requests from listeners, and as long as I thought they were decent enough music, I played them also.

It turned out, to my surprise, that quite a few people were listening, decorating their trees, wrapping presents, and doing other typical Christmas Eve activities. While a few callers didn’t like going from Gregorian chant to Ella Fitzgerald, most people enjoyed the program. I wound up doing a Christmas Eve program every year during my eleven years on WDST. I didn’t always manage to make time for my favorite Christmas work, the “Midnight Mass” of Marc-Antoine Charpentier (based on old French carols). But I played it most years, and I played “Holy Babe” every one of those eleven years. Sometimes people even called to make sure I would have it on before they had to go to sleep. I continued to take requests, but there were some things I would not play. “Grandma Got Run Over by a Reindeer” was one of them.

It was during those years that I became acutely aware of how little many “Christmas” songs have to do with Christmas. And fewer still are “Christmas carols,” a term that sometimes gets applied even to such non-Christmas winter songs as “Baby, It’s Cold Outside” and “Jingle Bell Rock.”

A carol is a “joyful religious song celebrating the birth of Christ,” according to Dictionary.com. “Rudolf the Red-Nosed Reindeer” is not by any stretch of the imagination a Christmas carol. It is, in its oblique way, a Christmas song, since in the U.S. we have come to accept the whole mythology of Santa Claus and his sled drawn by reindeer (presumably the wildlife normally found closest to the North Pole capable of pulling anything heavy). That image doesn’t fly in most other countries, but I’m not trying to become a cultural dictator so I’ll accept Christmas any way we want it here in the U.S.

Still, there are many, many songs typically played at Christmas time which have nothing to do with Christmas in any way. Here are some of what I call Winter Songs which have no Christmas relevance at all:

Jingle Bells

Sleigh Ride

Let It Snow!

Winter Wonderland

Frosty the Snowman

All of these appear (one of them twice) on the latest edition of an Ella Fitzgerald Christmas compilation, “Ella Wishes You a Swinging Christmas.” There is no singer I esteem more than Ella Fitzgerald. But she either she didn’t know the difference between Christmas carols and winter songs or she didn’t care.

Writing the informal essays that I contribute to this site takes me back to my teens, when I was very much involved in science fiction fandom. The kind of writing I do here evolved from the fanzines I wrote for and sometimes published, and from writing I read at that time.

These days the term “blog” covers a much wider range of formality than I was used to in the past. There are now thoroughly professional “blogs” on line. I still think of the blog as a loose, informal style descended from the great essayists of the past, like the French Renaissance writer Montaigne–who popularized the genre–and the English writers Joseph Addison and Richard Steele, whose “The Spectator” (1711-12) was the Huffington Report of its day.

There were two highly diverse writers of my teens whose inspiration I still feel, both named Harry. One of them was widely known to the public: Harry Golden. The other was known only to science fiction fandom and the inhabitants of his home town: Harry Warner, Jr., the Hermit of Hagerstown.

I subscribed for several years to Golden’s weekly “newspaper” The Carolina Israelite. He wrote and published it from 1942 to 1968. I read it in the 1950s, and of course read his collections of columns, starting with the best-selling “Only in America.” I remember Golden, whom I haven’t read in a long time, as a superb informal essayist. He wrote reminiscences of his own life, including (after it was exposed) a frank discussion of time he had spent in prison for fraud following the 1929 crash. He became famous for “The Vertical Negro Plan,” a marvelous satiric essay in which he observed that racial integration was a problem only in places where people sat down. His solution to the problem was to remove seats in places where integration was a contested issue, like lunch counters and schools.

The content of Golden’s writing was interesting and sometimes challenging. But what made him so popular was his amusing means of expression. You could read a Golden essay on virtually any topic and remain engaged because he made you smile. “Only in America” was his fourth book, but it was the first one collected from the Israelite. Readers quickly discovered how entertaining Golden’s writing was and the book became a huge best-seller. He also came across well in frequent radio and television appearances.

Harry Warner, Jr. was a very different sort of person and writer from Golden. He was a newspaper reporter in his home town of Hagerstown, Maryland, who became interested in science fiction and science-fiction fandom in their early days. He published his first fanzine in 1938, and continued active in fan writing until he died in 2003. He also wrote some science fiction and a book-length history of fandom, “All Our Yesterdays.”

Harry was a voluminous correspondent, sending a letter of comment to any fanzine he received and answering all letters. I began writing to him occasionally when I was in my mid teens. We had some things in common that we both appreciated. We were both greatly interested in classical music. I was a poor piano student. Harry was an accomplished pianist and oboist who performed locally. We both wrote music reviews.

For decades, Harry was a mainstay of the Fantasy Amateur Press Association (FAPA), a group which circulated fanzines published by its members to those members. Some of these fanzines went only to FAPA members; others had some outside circulation. Harry sent copies of his Horizons to me for several years. His training and discipline were awesome. He would start out with a quire of mimeograph stencils (24), compose his writing directly onto the stencils, and finish his last essay on the last line of page 24. As I recall the essays were bloglike, informally written and not the products of great research or contemplation, yet they were always interesting to read.

Harry got his nickname, “the Hermit of Hagerstown,” from his reluctance to travel or to engage in much personal contact with others outside his work. I was one of the few science fiction fans who got to meet him on his home turf. In 1960 I went to Franklin and Marshall College in Lancaster, Pennsylvania, within a few hours of Hagerstown. I was there for only six months, but during my fall semester I maintained my correspondence with Harry and he invited me to visit him. I got a ride with a classmate to Hagerstown, returning to Lancaster by bus. Harry was very welcoming and genial, taking me to eat in his favorite places. We spent the evening listening to some favorite classical recordings. It was a real treat.

I dropped out of science fiction fandom in my late teens and lost touch with Harry. I was a little surprised to learn that he had remained active until the end of his life. Now I regret that I didn’t write to him years ago and share with him details of my activities as a classical music critic, record dealer, and publisher. I’m sure he would have been pleased.

I still remember the writing of these two Harries, and I remain happily influenced by both of them.

About a year ago, I was surprised to get a hit from eBay on my Leslie Gerber search. Someone offered an APAzine that I had written and published. (It wasn’t from FAPA, which I never did get into; it had a very long waiting list.) The first page was posted in the offering, and I got to read it. I wrote about the some of same things that interest me today, including classical music and literature, as well as personal comments answering things other people in the group had written about. I was fascinated to encounter my teenage self in this way and would have liked to read the whole thing. But somebody outbid me.

In the post office lobby, there are three bins labeled WASTE. They have always been there as long as I can remember, and I’ve had a post office box there for more than three decades. Several years ago, two new containers were added, right next to a table which contains one of the waste bins. They are labeled RECYCLING. They have slots at the top to prevent people from throwing obvious trash into them, but you can still get a thick catalog or a telephone book into one of them without difficulty. I was delighted at the appearance of these containers and I use them for all my junk mail.

So do lots of other people. But not all of us! When I look into the waste bin which is right next to the recycling containers, there is always paper in it. Lots of paper. For a while, I used to fish out paper and put it into the recycling containers, and I still do that sometimes. But I’ve mostly given up.

The openings in the waste bins are larger. It’s easier to throw things into them. If you don’t think about anything, that’s what you would do.

But even the waste bins aren’t enough for some people. Many postal customers use self-seal envelopes and mailers, which require you to remove a strip of slick paper in order to close them. I seldom make a visit to the post office when I don’t see some of these strips lying on the work tables or on the floor. People just drop them carelessly, like smokers dropping cigarette butts.

I also frequently find postal forms, conveniently supplied in dividers on the work tables, left on those tables, or dropped on the floor. Someone who wanted to use one of these forms and accidentally took out two couldn’t be bothered to put the extra one back.

Don’t get the idea that the post office is a neglected place. I frequently see the postal clerks, when they aren’t busy with customers, out in the room picking up things.

Who are the customers who get mass mailings, like notices from the local school district, and leave them on the table for others? Sometimes there are large piles of them. Do people think that somebody else coming to the post office is going to want these notices and won’t get them?

I even know what happens to our local recycled paper. I wipe my ass with it. It’s bought by Marcal, whose paper products I buy whenever I can because they are made from recycled paper and have been for more than half a century. I’m sure Seventh Generation is doing good work, but Marcal has been doing the same things with paper since the guys who run Seventh Generation were born!

Am I over-reacting? Could be, but I’ll bet that in China and Korea you won’t find this kind of negligence and waste. Is that why those countries are whipping our asses economically these days?

I was probably the least talented and least able piano student Piero Weiss ever had. He got stuck with me in 1969, when I was living on Staten Island. I had found an excellent piano teacher who lived just a few blocks from my house, but her husband got a job in Los Angeles and they moved away. Thinking cleverly for once, I wrote a letter to Jacob Lateiner, a pianist I greatly admired but did not yet know. (Later he became a friend.) I described my level of ability as honestly as I could and asked him if he could recommend a teacher who would take me. He recommended Piero Weiss.

Mr. Weiss, as I called him in those days (later we became Leslie and Piero, but only after I was no longer his student) must have found me a trial as a student. I had no hopes or ambitions of playing on anything near a professional level. As a young man with a wife and three children to raise, I was lucky if I could manage an hour a day to practice, and often I couldn’t. But I came for lessons faithfully every other week, even after I moved to upstate New York the following year. Although I was a poor student, I was otherwise well informed about music, already writing professional record reviews. So even though I was unable to put my knowledge into practice very well, I must have been interesting enough to keep him willing to teach me.

Piero actually taught me more about playing the piano than I had any right to know. I was unsatisfied with the sound I usually produced from the piano. He taught me to listen, assuring me that conscious attempts to alter my sound would probably not work but that concentration on listening would lead my fingers to produce something closer to what I wanted to hear. He also showed me some elements of the technique he had learned from his own teacher Isabella Vengerova, of which I remember the use of the wrists to produce changes in volume, especially strong accents.

One of the aspects of his teaching I particularly remember was the way he would help me select repertoire to study. He often made suggestions. When he asked if I ever had played Schubert and I said I hadn’t, he said, “What’s the matter? Don’t you like Schubert?” “I love Schubert,” I replied. “That’s why I don’t want to play his music.” But he selected for me just the right Impromptu to fit my technique. When I mentioned something I would like to play, he would zip through the score from memory, no matter what it was, and tell me whether he thought I would be able to play it or not. I did surprise him once. I said I wanted to play Beethoven’s Op. 10, No. 2, and he said I would not be able to handle the finale. I worked like a demon for two weeks and came back with that movement comfortably in hand. He was surprised, and gratified.

Piero frequently played for me at lessons, usually just brief excerpts to show me how something should go. He was obviously a superb pianist, and I asked him why he had not pursued a career as a performer. He told me he didn’t have the confidence. But he played me with pride the recording of his performance of the Mendelssohn First Piano Concerto from a Lewissohn Stadium concert. And he gave me a duplicate copy of one of the two LPs he had made for the German record club Opus. I found the other one decades later.

After one lesson, we somehow got into a discussion of the Schumann Toccata. “I used to play that,” he told me. He was still sitting at his piano, and he turned to the keyboard and began to play. He played superbly, with great power and fluency and surprising accuracy. When he had finished, he looked at me and said, “I haven’t played that in twenty years.”

After I “mastered” the Schubert Impromptu to the best of my ability, I asked if he thought I could learn one of the Schubert Piano Sonatas. I was particularly interested in the little Sonata in A Minor, D. 784. He pointed out to me that the finale was beyond my ability, and then told me he hated to teach that piece anyway. He had once had a talented woman student who wanted to play that Sonata. He had told her that the last measures of the finale, in octaves, were very difficult, and that she could not play the movement any faster than she was able to play the octaves because it was improper to slow down for them and spoil the momentum of the music. When she played the Sonata for him, she did slow down for the octaves, and he told her she could not play the music like that. She became angry and never returned.

At one point I fell in love with the Brahms Intermezzo in B Flat, Op. 76, No. 4. Piero encouraged me to give it a try. It didn’t really suit my limited ability, and although I could get through the notes, I was not able to make the piece flow. He kept encouraging me to work on it, but I brought it back for several lessons and it never sounded right. At one lesson, after I lumbered through the piece, I told him I wanted to give it up. “No,” he said. “Work on it for two more weeks, then play it for me and then you can give it up.” I did my best, but the day before the lesson it still sounded lumpy. I came in and said I was ready to quit and didn’t want to play it even the one more time. He told me to try it anyway. I did, and amazingly, that time, I played it very well. When I finished, he said, sounding very surprised, “That was beautiful!” “I know,” I replied, just as surprised. I never played it again. Thinking about the experience later, I suspected that he was not surprised at all. He knew exactly how to push me–like the zen master who told a student in search of enlightenment that if he did not succeed within three days he should kill himself.

I had the opposite experience when I attempted a speedy Scarlatti Sonata, K. 545. I worked hard on it and came to my lesson confident that I would be able to play it quickly and accurately, and I did. When I finished, he looked at me and said, “Mr. Gerber, that is the worst thing you have ever played for me.” It sounded cruel, but he was right; I had just gone for speed and accuracy and forgotten that I was playing a piece of music. He helped me learn to shape the piece so that even at rapid tempo it still made musical sense.

One incident that occurred during our relationship made a lasting impression on me. After a lesson, Piero told me that he had learned about a German musicologist named Wolfgang Boetticher (not to be confused with the cellist and conductor Wolfgang Boettcher) who had been invited to speak at a conference in the U.S. on Robert Schumann. There was no doubting Boetticher’s credentials as a Schumann scholar; he had edited the Henle Urtext of Schumann’s piano music. But Piero also knew that during the Nazi era Boetticher had worked for the government to help locate and identify collections of music and music materials owned by Jews so they could be confiscated. Apparently he was also a member of the S.S. Piero passed elements of the story along to his friend Anthony Lewis, then a regular columnist for the New York Times. After Lewis wrote a column about Boetticher’s background, the invitation was withdrawn. Piero was very proud and pleased, and I learned something about the strength and conviction of this gentle man.

I had relatively little contact with Piero as musical scholar, although I still have my inscribed copy of the book of composers’ letters he edited. I did take a lesson once at Columbia University, where he was teaching, and I got to meet his office mate, Richard Taruskin, who later became a regular customer of my mail order record business. We had some conversations about Italian opera, a favorite topic of his and not one of mine. Although I had grown up in an opera household, and attended occasional Met Opera performances from the age of ten on, I had never become a real devotee of the opera. Piero did his best to convince me of the greatness of Verdi, but it has taken me until recent years to realize how right he was. I am still not convinced by his arguments in favor of Franz Liszt. Piero insisted that all of his music had to be taken seriously, but I still think Liszt wrote both masterpieces and bombastic trivia.

Eventually, not even Piero’s encouragement could keep me at the keyboard, and I reluctantly gave up my lessons, my piano study, and even my piano. But we remained in touch over the years, mostly with occasional phone calls. After he went to Baltimore to teach at Peabody, he told me with great pleasure that he had gone back to playing the piano in public and was performing at faculty recitals. Earlier this year, I spoke with him several times after our mutual friend Jacob Lateiner died, telling him that I was working on publishing a Lateiner memorial CD set. I last spoke with Piero a month before he died, telling him that publication of the Lateiner set was imminent. I regret that he never got to hear it.

“Adventure Shopping” is the actual motto of one of my favorite stores. As someone who has been prone to careless, compulsive spending in the past, I have to watch carefully anything which links spending money to a sense of fun. And I do. But I still do need to buy things, and as long as I am going to buy the things I actually need, I like to make the experience enjoyable rather than tedious.

“Adventure Shopping” is the actual motto of one of my favorite stores. As someone who has been prone to careless, compulsive spending in the past, I have to watch carefully anything which links spending money to a sense of fun. And I do. But I still do need to buy things, and as long as I am going to buy the things I actually need, I like to make the experience enjoyable rather than tedious.

One of my favorite stores ever was a nearby place called Kingston Liquidators. The store was run by a man who had earlier run an extensive closeout operation on Long Island called Sands Salvage. When he opened up in a large facility on Route 28 near the city of Kingston, he created a must-stop location for me. Not long afterwards he opened an even larger store just outside of Saugerties called Weekend Liquidators. When the owner of the Kingston Liquidators insisted on a large rent increase, the store shut down and all operations were transferred to Weekend Liquidators, which expanded its hours from two to five days but kept the name.

The Liquidators stores were true salvage operations, offering merchandise picked up in bankruptcies, closeout sales and other such business disasters. The types of merchandise were fairly consistent, but you really never knew what you might find on a specific visit. However, there were almost always lots of packaged food items at extremely low prices.

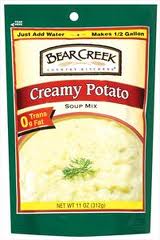

My favorite, which was frequently available, was a Bear Creek brand potato soup mix, really delicious stuff. I can still get a small package which makes about eight servings for $5 to $6, but the Liquidators sold large cans which made 48 servings for $8! At the time they were available, I was hosting a weekly pot luck gathering at my home—an event I really miss today. (We recently revived these meetings monthly.) Since I never knew in advance what people would be bringing, I sometimes needed to make something quickly and the Bear Creek mix became known as Emergency Soup.

My favorite, which was frequently available, was a Bear Creek brand potato soup mix, really delicious stuff. I can still get a small package which makes about eight servings for $5 to $6, but the Liquidators sold large cans which made 48 servings for $8! At the time they were available, I was hosting a weekly pot luck gathering at my home—an event I really miss today. (We recently revived these meetings monthly.) Since I never knew in advance what people would be bringing, I sometimes needed to make something quickly and the Bear Creek mix became known as Emergency Soup.

Over the years I bought clothing, appliances, and various household goods at the Liquidators stores, always at huge savings. Once I even found the DVD set of one of my favorite TV shows of all time, Mr. Bean. Eventually the owner of the store became ill and it closed. It was briefly revived in the town of Boiceville (under the original business name, Sands Salvage), out of my usual orbit but a place I visited occasionally. One of the store’s main attractions, low priced food, was no longer carried because it was near a grocery store and the lease prohibited it from carrying food. Now that store is also closed.

I’ve noticed that “job lot” chains tend to follow a regular pattern of flourishing and disintegrating. This occurred with the original Job Lot chain, which I remember from visits to New York in the 1970s. The stores start up with the same business model followed by the Liquidators stores, buying up surplus, damaged, or discarded merchandise. Eventually, though, their success leads them to expand to the point where they can no longer fill the stores with enough bargain merchandise, so they start creating their own, having things especially made for them to sell at low prices. This is the beginning of the end. As the quality of the merchandise deteriorates, business falls off and eventually they close.

This might happen some day to the “Adventure Shopping” chain, Ocean State Job Lot (originating, as its name indicates, in Rhode Island). I first encountered these stores on Cape Cod, where I would go often to visit my parents at their summer home and now visit because the home has become mine. There are Ocean State Job Lot stores scattered around the Cape, including one in Hyannis which I used to visit frequently until I realized that it was messier than the others. These stores, originally selling closeouts strictly, have become hybrids, selling discount merchandise alongside of things that are just made to be sold cheaply, often for the chain. And it has continued to expand, to various locations around New England and now to a village (Valatie, New York) less than an hour from my home in Woodstock. But OSJL still has plenty of closeouts, from remaindered books to last season’s clothes to brand name pet supplies, and I still go there whenever I pass by. OSJL has lots of food, sometimes including the organic products I favor at surprisingly low prices.

None of these stores will ever match in my affections such specialty shops from my past as the Discophile record shop on West 8th Street in Greenwich Village or the superb Wheat Fields food store in Woodstock. I wish I could have them back.

I’m always in search of interesting material to listen to in my car on long drives with my wife. We like lots of different kinds of music, but her interest in audiobooks diminished after she suffered a brain injury. Her favorite listening has been Spike Jones and His City Slickers, but there’s only so much of that hilarity available.

Recently my car’s CD player started to fail, and I decided to replace rather than repair. Unfortunately the difficulty in obtaining a new unit which included a cassette player closed off a lot of possibilities in our old collections. But more possibilities opened up when I learned that my new player was capable of playing MP3 discs. I had a few of these but was able to play them only on my DVD player at home.

Searches on eBay opened up to me the world of OTR (“old time radio”) MP3s. Various dealers have an astonishing variety of old radio broadcasts, which they claim are public domain material and therefore free of copyright. (This doesn’t accord with my understanding of current U.S. copyright laws but wotthehell.) From the bewildering number of choices, I decided to try a few discs, one of which included 60 (!) programs of the old Groucho Marx “comedy quiz show” “You Bet Your Life.” They were big hits with both of us. Within a couple of months we had listened through the entire disc. As we neared its end, I did another search and found another seller (in the U.K.!) who was offering a disc with 209 “You Bet Your Life” programs. It arrived just before we exhausted the first disc. These listings come and go so rather than providing a link I’ll just suggest you try eBay if you’re interested.

There are also plenty of “You Bet Your Life” TV shows available on DVD. Some of them are very low priced “public domain” issues of variable quality. But the excellent Shout! Factory label has issued two boxes of programs. (The second one, “You Bet Your Life – The Lost Episodes” includes the appearance of Lord Buckley as a guest.) Some of the PD issues are of surprisingly good quality, but they include the now-boring De Soto-Plymouth commercials, edited out in the Shout! Factory issues. For most of the decade-plus run of the show, there were separate radio and TV programs every week. The Shout! Factory collections are the best ones, but if you’re willing to sit or fast-forward through the commercials the 13 episode collection “Comedy Legends Series – Volume 1

” is good and cheap.

While we watched our way through a disc of TV shows during a recent vacation, I’ve been dealing mostly with the radio programs. When you listen to so many programs in such a short period of time (we’ve now heard over a hundred, some of them twice) patterns emerge. Groucho’s humor becomes pretty predictable. He will never pass up an opportunity to make politely suggestive remarks about women contestants, some of which would be considered offensive today. (He almost invariably refers to them as “girls.”) Another favorite type of joke consists of pretending he hasn’t heard a contestant correctly, or pretending he doesn’t understand an idiomatic expression and taking the words literally.

But damn, the guy is funny! He obviously got, and kept, the job because of the quickness of his wit, and it’s often pretty impressive. When his foil, George Fenneman (who also did announcements for “Dragnet”), got the chance, he could be rather funny himself. But he knew his role as straight man and performed it admirably.

One reason for the success of “You Bet Your Life” was the producers’ ingenious decision to record the programs in open-ended sessions and then edit them down to the desired length. On the MP3 discs, there are a few programs taken from unedited tapes, and it’s fascinating to hear the way the programs take shape. Groucho, freed by the knowledge that if a gag fizzled it would disappear, takes all kinds of chances. Plenty of them do fizzle. The editing is made plain when you are listening to a program with a readout of the elapsed time visible, and you can see how unequally the time is allotted to different pairs of contestants. Some of them get five minutes of air time, some fifteen.

The betting strategy is a constant source of amusement to me. In the classic radio shows, each pair of contestants was given $20 to start. They were then free to bet as much of their money as they wished on each of four questions. The couple which wins the most money then gets a chance to answer a big money question, for $1000 plus $500 for each week that the big prize hasn’t been won. Almost inevitably the contestants start by betting $10, obviously wanting to stay in the contest if they miss the question.

This makes me wonder if any of them had ever heard the program before. The questions in the first round are sometimes tricky but mostly quite easy. I answer most of them correctly except for ones dealing with current events. The contestants answer most of the questions correctly too. Sometimes they bomb out, and I remember one program where contestants wound up winning only $20 but still got the chance at the big money because the other two couples lost all their money. (When that happens, they get a chance to win $10 by answering a question like the famous “Who’s buried in Grant’s Tomb?”)

Do the math. If you start out winning $10 on your first question (total $30), and bet all you have on the three subsequent questions, your maximum winnings add up to $240 (and few bet all). If you start out winning $20 on your first question and bet all, your maximum winnings are $360. Since few contestants who miss any question wind up with the highest score anyway, it would have made sense to bet everything on each question. Sometimes I feel like shouting at these poor people, almost all of whom are dead by now anyway. The “big money” questions tend to be rather difficult; while I haven’t been keeping score I’d say they are answered correctly less than half the time.

The compilations we’ve been listening to aren’t ideally prepared. They aren’t strictly chronological (easiest to track by the amount of money offered in the final question), and the sound quality is variable. But they are almost always intelligible, which is all that really counts. It’ll be a while before we get through episode 209 on the current disc, but we’ll be sad when we do.

Recently my appetite for jazz and blues recordings, going back to my mid-teens, seems to have increased exponentially. As a result I have been taking advantage of some wonderful opportunities to acquire jazz and blues CDs in large quantities at very small prices. Over the next few weeks I will be writing about some of these acquisitions. Right now, though, I’m working on a couple of mysteries presented by one segment of a big box.

The History label, one of several such projects from German CD companies taking advantage of European laws on sound copyright, has issued quite a number of genuinely historical compilations of both classical and non-classical material. Some years ago I acquired History’s “From Swing to Bebop” when I bought a large CD collection. It consisted of 40 CDs, in two-disc slim-paks collected into a (rather flimsy) box. I listened all the way through the set, enjoyed most of it, and kept it. (It now lives in my vacation home, on Cape Cod, where it often serves as dinner music.)

Not long ago, while browsing through jazz and blues CD boxed sets on Amazon, I ran across another History 40-disc set, “Nothing But the Blues.” Someone was offering it at a quite reasonable price. Assuming that it was out of print–which does seem to be the case–I bought it promptly and have been gradually listening my way through it.

One of the two-disc boxes particularly attracted my attention: “Night Time Blues,” including one disc each of Ma Rainey and Memphis Minnie. They are both favorites of mine. History’s two-disc boxes (which may have been available separately, and do show up that way as used items) include little booklets with listings, brief program notes, and dates and personnel for each recording, very necessary information for my inquiring mind.

On two of the Memphis Minnie selections, one from 1935 and the other from 1936, she is accompanied by a pianist identified in the credits as “Black Bop.” This mystified me. And I was curious, too, because whoever he is “Black Bop” is a pretty hot pianist.

As he was indeed. It turns out that “Black Bop” is actually just a silly typo for “Black Bob” Hudson. “Black Bob” is described by allmusic as a “ragtime-influenced blues pianist,” which he certainly was. There seems to be little biographical information about Hudson, except that he had a banjo-playing brother named Ed who also recorded widely, often in the same sessions as his brother. Both were members of the Memphis Nighthawks; Bob was one of the Chicago Rhythm Kings. These are both groups I’ll have to investigate. Bob also recorded with a number of other well-known blues performers, including Lil Johnson and Charley West.

It’s a bit of a surprise to hear someone who plays that well whose work I was completely unfamiliar with. But my listening through jazz and blues sets and looking at the personnel listings have led me to many such experiences in recent years. It was in a compilation of Commodore label jazz recordings that I first noticed the saxophonist Don Byas, who has become one of my all-time favorite jazz performers even though until I was in my early sixties I’d never heard of him. Now I’ll be looking for more of the ragtime-influenced hot piano of Black Bob.

Another odd credit appeared on one of the Ma Rainey items. Most of this great singer’s recordings are decidedly in the “urban blues” style, and the ones on this disc feature such well known jazz musicians as Louis Armstrong, Fletcher Henderson, Don Redman, and Thomas A. (“Georgia Tom”) Dorsey (later to become a famous composer of gospel songs). However, the first two, and earliest tracks, “Shave ‘Em Dry Blues” and “Farewell, Daddy Blues,” are credited to “Guitar Duet, Possibly Milas Pruitt And Another.” This piqued my interest especially when I listened to the recordings, which I don’t recall hearing before. The guitar accompaniments sounded so much like the famous “Lead Belly” (Huddie Ledbetter) playing his twelve-string guitar that I was startled. (Incidentally, the sound on the CD is much better than on the link I’m providing.)

The first result of my research was, surprisingly, to rule out Lead Belly. If you know his work, and you hear these tracks, you’ll be astonished to learn that they are not his playing. They so strongly resemble his style and sound that it’s hard to believe he’s not playing. But in 1924, Lead Belly was still in a Louisiana prison, and it’s not likely that he was released to make recordings with Ma Rainey.

However, Milas Pruitt did often perform as a member of a guitar duet. His partner was his identical twin brother, Miles Pruitt. While some sources claim Rainey’s accompanist on this record was Papa Charlie Jackson, most credit the Pruitt twins, and it’s quite believable that two guitarists playing in unison would produce a sound that resembles a twelve-string guitar. How they got Lead Belly’s style down so well is something I doubt I’ll ever learn. Actually, its very unlikely that they got the style from Lead Belly at all. They were from Kansas City, not Louisiana. (They also made recordings with another major early blues star, Ida Cox, and with other singers of the time.)

Well, here I am in my mid-sixties, still learning more and more about the music I love. As I continue to explore the wealth of new material coming into my collection, I’m sure I’ll be finding more new favorites. Watch this space.

Being a relatively goal-oriented type, I have never been able to sympathize with the urge to ride motorcycles–or, for that matter, to go sky-diving. The sensation of freefall doesn’t appeal to me, and neither does the idea of tooling along a hard road at 60 miles per hour (or faster) without the protection of a heavy metal frame around me.

Being a relatively goal-oriented type, I have never been able to sympathize with the urge to ride motorcycles–or, for that matter, to go sky-diving. The sensation of freefall doesn’t appeal to me, and neither does the idea of tooling along a hard road at 60 miles per hour (or faster) without the protection of a heavy metal frame around me.

Still, that’s no reason for me to hate motorcycles. I don’t want to dictate other people’s behavior except as it impinges on my own. I do think that motorcyclists should have a completely separate insurance pool so that their high fatality rate (see Tom Vanderbilt’s fascinating book “Traffic”) should not cost me money. But as long as that applies, and their behavior doesn’t impinge on my life, motorcycles are none of my business.

Ah, there’s the rub.

Most motorcycles in my area do impinge on my life. And it’s because most of them constantly violate the law.

If I drove a car that made as much noise as the average motorcycle does, I’d get a ticket. In fact, it happened to me once, shortly after something flew up from the road and banged my muffler, destroying it. I took the ticket with good grace, explained the situation to the judge, and paid a small fine.

But most motorcycles drive around with their mufflers deliberately bypassed or removed. The cyclists call them “straight pipe,” meaning the exhaust pipe is just that, a pipe that runs straight out of the engine without encountering any obstacles. No motorcycles leave the factory set up like that. They couldn’t be sold legally anywhere in the United States. So the straight pipe cycles are illegally altered by their owners or mechanics, and they ride around making hideous amounts of noise with impunity.

I once asked a local policeman why he never gave a motorcyclist a ticket for riding without a muffler. He couldn’t give me an answer; he really didn’t know why, except that nobody did it.

So here I am on an unexpectedly warm and sunny day in October, sitting on a bench on the main drag in Woodstock, reading poems from a just-purchased book (by the excellent Georganna Millman) to my wife, being forced to stop at least once per poem to let the noise of a motorcycle or a group of them go by.

During the wonderful Maverick Concerts summer season, in a small wooden “music chapel” well off a side road, Beethoven String Quartets are often blotted out by the noise of motorcycles roaring past.

And why do these motorcyclists make their machines noisy, risking their hearing (which they inevitably damage) and the wrath of the people they pass? Because they like the noise.

That policeman who told me he never ticketed noisy motorcyclists said that it would be difficult to prove a motorcycle was noisy without measuring it as it passed on a sound level meter. (The cop who gave me a ticket for a noisy muffler had no such problem.) I suggested to him that simply driving a motorcycle without a muffler was proof enough, but he said it wasn’t. You had to catch the noisy cycle in the act.

OK. Following that line of reasoning, it seems I could take action on my own. Theoretically I could buy me a big shotgun and sit myself down at the intersection of Routes 212 and 375 where most traffic arrives in Woodstock. When I hear a straight pipe motorcycle, I could just blast the hell out of it. If I caught the rider too, well, too bad, just collateral damage. When the cops came to bust me, I’ll could explain to them that they can’t arrest me because they didn’t catch me in the act.

I’ll have to consult my lawyer on this. We’ll see what he says.

(Incidentally, my title is paraphrased from the composer Lou Harrison, who titled a movement in one of his orchestral works “A Hatred of the Filthy Bomb.”)

The poor die here in the streets

and are quickly paved over.

Their bodies may not be allowed to disrupt

the flow of money through the gutters.

Money! it’s all that counts here.

You all must know–don’t you?–that this politics shit

is just a shadow play

to divert attention away

from the flow of money.

Black and white,

woman and man,

we grab onto

as much as we can.

Dollar bills are too trivial, too bulky,

too easy to find and follow.

We deal in billions here, my friends!

Have you ever seen a billion dollar bills?

Of course not. Your eyes

can’t reach that far.

But our money, the real stuff, has no physical body.

It’s electronic, ethereal, almost spiritual.

Every once in a while, one of the news fools

finds out something about the money, or our fun.

Next thing you know, she’s got her own show

on Fox Noise, and the story goes to sleep.

Our fun, yes: money buys us:

little boys with tight pulsating assholes;

tight young women who drool at the sight

of rich fat old men; finest Afghan leather

bondage straps; and doctors

who can cure anything we pick up.

This is what we dreamed of in our teens.

Everything we ever wanted, only better.

No limits. None. This country generates

trillions of useless dollars. Why waste any

on so-called citizens who don’t have the brains

to steal it for themselves?

Better we should spend it

making sure they know

whom to vote for.

What’s really fun is watching movies

about how bad we are.

People go to see them. Get mad. Seethe.

Foam at the mouth, drool on the floor

where their saliva is soaked up

by the crushed remains

of industrial popcorn. Meanwhile,

guess who owns the movie studio,

the distributors. the theaters.

Who rakes in the admission price.

Who fucks the starlets.

The guy who invented the machine

that wraps fake cheese slices in cellophane

just gave a million dollars to my campaign.

Our Supreme Court said it was OK.

Gonna ask him for a million more.

I was already a fan of Richard Thompson before the first time I heard him in person. That event occurred in St. Petersburg, Florida, more than 20 years ago. My wife and I were vacationing in the area and when I heard that Thompson was playing I had to go to hear him.

I was already a fan of Richard Thompson before the first time I heard him in person. That event occurred in St. Petersburg, Florida, more than 20 years ago. My wife and I were vacationing in the area and when I heard that Thompson was playing I had to go to hear him.

When we arrived at the venue we were considerably unimpressed. It was a seedy-looking bar with a total of one chair in the entire place. We got there early enough to secure that chair, where my wife sat sipping white wine and waiting for something worthwhile to happen.

That took quite a while. The show started late, and opened with a local woman folksinger who had nothing worthwhile to offer. After a few minutes, my wife Tara started looking at me and mouthing, “Let’s get out of here.” I insisted we wait. Once Thompson began singing, Tara took my hand and beamed.

Since then, I’ve heard Thompson in three different nearby venues. He performed once with his band at the Bearsville Theater, which seats about 250 people, three miles from my home. The place was packed. He’s also performed once at the Bardavon 1869 Opera House in Poughkeepsie–the theater where Ed Wood got his start in movies, as an usher. That place seats almost a thousand people, and it too was full. Most often, we have heard him at The Egg, a complex of two theaters in Albany. He performed, with and without his band, at the larger Carlisle Theater, which also seats almost a thousand (and has no bad seats). The hall was never sold out, but it was usually about 90% full.

The hall was about 90% full when Thompson performed his solo act there on October 13. But after being announced for the Carlisle Theater, he was moved to the Swyer Theater, less than half the size of the Carlisle. This seems to be a drastic falling-off of attendance since the last show, by about half. Perhaps most Capital District Thompson fans prefer the band, although I’ll never go to see it again. The last time, although the performance was spectacular, the volume was so loud it hurt my ears. (In correspondence I learned that The Egg’s director agreed with me but blamed the traveling sound man who came with the band. Well, nuts. It’s not his theater.)

Then again, maybe the problem was that Thompson was performing the following night at the Mahaiwe Theaterr in Great Barrington, Massachusetts, about half an hour away….

Still, what is there left to say about this man? Probably nothing new, but I’m inspired to rehash anyway. I think Richard Thompson is one of the most remarkable performers I’ve ever heard. Usually, when I hear a singer-songwriter-instrumentalist, one of those aspects is most outstanding and the others follow behind. Not with this guy! He is one of the greatest guitar players I have ever heard, and he’s not limited by any genre. While he does have a basic folk style, he plays it with more elaboration and virtuosity than anyone else I can think of, and he’s just as adept as a rock guitarist. (Some day I’d like to hear him try a movement of Bach. He obviously has the chops.) In one of his performances at The Egg, an obscure but highly amusing Frank Loesser version of “Hamlet,” he gave a convincing impersonation of a 1940s jazz guitarist. He sings with tremendous power and range, with breath control an opera singer might envy, and his diction is among the clearest I’ve ever heard. And as a songwriter, he is one of the geniuses of his time. Many other performers use his songs, often to great effect, although it’s rare that anyone can outdo Thompson in his own material. His lyrics are memorable, and his melodies are accompanied by harmonic and rhythmic complexity far beyond the ambitions of most songwriters.

At this show, I was especially struck by a song called “Pharaoh,” which sounded as though it had been written as a theme song for the Occupy Wall Street movement (which I had joined, although at Wall Street in Kingston, New York, earlier the same day.) It wasn’t until I got on line that I discovered the song was first recorded in Thompson’s album “Amnesia” in 1998!