When I first heard the pianist Simone Dinnerstein, I was very favorably impressed with her playing. Perhaps that helps to explain why I have been so disappointed in her recent development.

Dinnerstein’s performances with cellist Zuill Bailey at Maverick Concerts were splendid. One time they played all of Beethoven’s Cello Sonatas in one concert. (They also recorded them for Telarc.) And at the Bard Music Festival devoted to Aaron Copland, she played Copland’s “Piano Variations” with such intensity that I was literally in tears at the conclusion. I can understand why Copland told a friend that the “Piano Variations” was his favorite among his works. Dinnerstein played it better than anyone else I’ve heard–and I’ve heard it many times–except for the composer’s own recording.

I’d actually been hearing about Dinnerstein for several years before I actually heard her play. Her father, a well-known painter, is a friend of one of my best friends, and I’d been hearing from him about Simone’s prodigious talent. Hearing her in person confirmed the reports.

So I was excited, five years ago, by the chance to hear Dinnerstein play Bach’s “Goldberg Variations” nearby, at Bard College, and I went with high expectations. I was appalled by what I heard. She seemed to have no idea of proper Bach style, frequently deviating from regular meter to make exaggerated expressive points. I don’t say that Bach playing has to be rigidly metronomical to be “correct.” But Bach is a baroque composer, not a romantic, and the power of constant rhythm is an essential aspect of his music. Dinnerstein played as if she were totally unaware of this aspect.

The performance was quickly followed by a recording, issued by Telarc. I heard it, and it was similar to the live performance I had attended. While some reviews shared my outlook, others hailed the disc as a “fresh” outlook on Bach’s music. The disc became such a best-seller (within the context of classical music sales, of course) that Dinnerstein was quickly snapped up by Sony Classical.

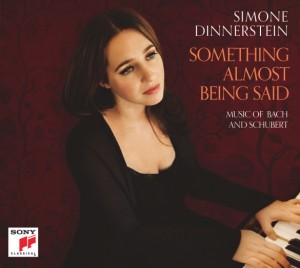

Dinnerstein’s third CD for Sony, entitled “Something Almost Being Said”, will be released on January 31, 2012. It represents a bit of a departure, since it’s not all Bach; it includes two Bach Partitas and also the first set of Schubert Impromptus, D. 899. Listening through it, one can tell that Dinnerstein is a well-equipped pianist. She has the dexterity and control to play demanding music in any way she wishes. And, at first, the CD, which begins with Bach’s Second Partita, sounds as though it might be a good one. Although there is some fooling about with rhythm in the opening Sinfonia, it’s still mostly well disciplined. But as the work progresses, Dinnerstein deviates more and more from strict tempo, reminding me of my reaction to a Bach performance I heard a couple of years ago. After a violinist’s rhythmically free playing of a fugue for unaccompanied violin, I wrote in a review, “Disrupting the rhythm of a Bach fugue to make a point is like interrupting sex to answer a telephone call.” It’s that disturbing. The final “Capriccio,” one of the most difficult movements in Bach’s keyboard works, is so fast it sounds hectic.

The Schubert Impromptus are no better. Dinnerstein’s tempo for the first, in C Minor, is so slow that the piece takes her 11:37 to play. By contrast, the great Artur Schnabel plays it in 8:53. For a piece of that length, 2 ½ minutes is a tremendous difference in time. And if you hear the way Dinnerstein starts to toy with the rhythm of the music at 4:25 of this movement, you may wind up as unhappy as I am.

But the worst example I can cite is Dinnerstein’s playing of the opening movement of the First Partita, played at a ludicrously slow tempo and with rhythmic freedom that would be excessive in Chopin. This is truly awful musicianship.

Dinnerstein is, alas, only the latest in a series of prominent musicians who have come to fame by playing in a manner I consider self-indulgent and unmusical. Such pianists as Ivo Pogorelich, Mikhail Pletnev, and Olli Mustonen have become great successes with performances that I doubt would have won them admission to any major music conservatory. Recently I heard a Chopin Prelude on the radio and said to my wife, “I don’t like this pianist.” It was Pogorelich. Mustonen, whose recordings had driven me crazy with their excessive rhythmic freedom, found a new way to antagonize me by recording a complete CD of Beethoven Variations and playing them with weird detachment and hyper-clear articulation.

One day I was listening to the radio and heard some unaccompanied violin music I did not recognize. It took me two minutes to realize it was the unaccompanied portion of Ravel’s “Tzigane,” music I know very well, but being played so freely it was unrecognizable. “Ah,” I said to myself, “must be Nadia Salerno-Sonnenberg.” It was. But some people like this kind of playing. Remind me not to invite them over for dinner.